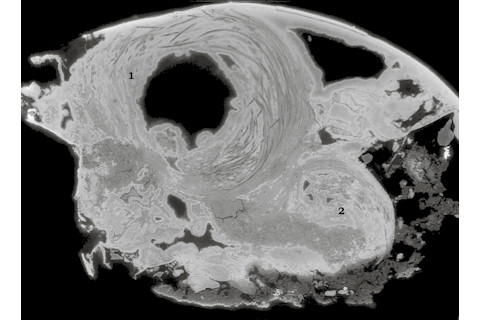

German biologist Renate Matzke-Karasz beamed at the virtual fossil slices on her iPad. “There are definitely internal structures in this animal, and perhaps even sperm!” she emailed retired Australian micropaleontologist John Neil, wanting him to be the first to know. It would take five more years to confirm, but Matzke-Karasz was actually looking at the oldest petrified sperm in the world.

The fossil was a 17-million-year-old ostracod, or mussel shrimp. It was one of nearly 800 specimens that Neil had painstakingly handpicked from sediment between 2007 and 2010. Such fossils usually just include the animals’ hard shells, not preserved soft body parts such as inner organs or sperm. But Neil’s samples came from a freshwater cave in Riversleigh, Australia, where millions of years’ worth of bat droppings left the sediment rich in phosphate, which petrified the ostracods’ soft parts.

“I thought that other body parts and organs might be preserved,” Neil says, “but the details were much greater than expected.” However, while he was familiar with their hard parts, Neil didn’t have much experience with analyzing ostracods’ softer tissues. He needed collaborators to fully understand his find.

By imaging inside the fossil, we can see the remains, coiled in two tight bundles (numbers 1 and 2), of the oldest petrified sperm in the world. | Renate Matzke-Karasz

Matzke-Karasz read his appeal in the 2009 issue of Cypris, a newsletter for ostracod researchers, and when Neil sent the data, she was impressed. “We were smashed by what we saw and immediately had the feeling that we should look inside,” she recalls. The European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble allowed her to do just that.

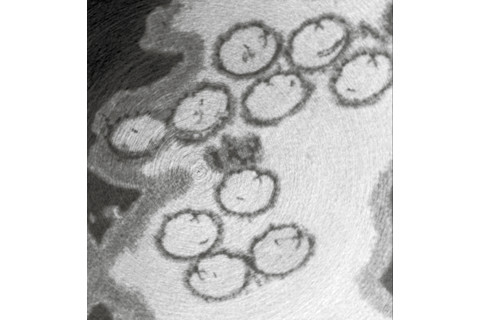

A cross section of the bundles of individual sperm cells reveals their structure. | Renate Matzke-Karasz

The scanners revealed the creatures’ sperm — along with sperm pumps and female canals and seminal receptacles — coiled up in the ostracods’ double reproductive system. (Males have two penises and females have two vaginas.) And at about 1.3 millimeters, the uncoiled sperm were relatively gigantic, longer than the ostracods’ bodies. Some insects and marine creatures evolved such larger-than-life sperm to block out competitors during mating. “I’ve run out of superlatives,” Neil says. “They are amazing in terms of the level of detail.”

[This article originally appeared in print as "Oldest Sperm Is No Shrimp."]