A shorter version of this story appears at Nature News.

In August of this year, Allison Noles rushed her bulldog Bella Mae to the vet. The dog’s face looked like a pincushion, with some 500 spines protruding from her face, paws and body. The internet is littered with such pictures, of Bella Mae and other unfortunate dogs. To find them, just search for “porcupine quills”.

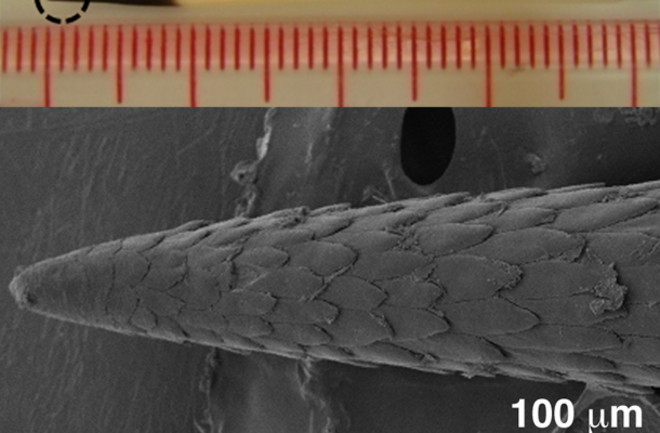

North American porcupines have around 30,000 quills on their backs. While it’s a myth that the quills can be shot out, they can certainly be rammed into the face of a would-be predator. Each one is tipped with microscopic backwards-facing barbs, which supposedly make it harder to pull the quills out once they’re stuck in. That explains why punctured pooches need trips to the vet to denude their faces.

But that’s not all the barbs do. Woo Kyung Cho from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Institute of Technology has found that the barbs also make it easier for the quills to impale flesh in the first place. “This is the only system with this dual functionality, where a single feature — the barbs — both reduces penetration force and increases pull-out force,” says Jeffrey Karp, who led the study.

Karp has spent many years developing medical adhesives, and he constantly looks to nature for inspiration. In 2008, for example, his team developed a sticky tape based on the feet of a gecko. More recently, he started thinking about micro-needles — a recent invention that uses patches of tiny needles to painlessly penetrate the skin and, say, deliver vaccines. These patches aren’t inherently sticky, but if they were, they could provide an interesting and more stable alternative to mere tape. And when it comes to sticky spines, what better animal to study than the porcupine?

Their quills are commonly used as jewellery by Native Americans, and they’re easily available. Cho ordered them off eBay in their hundreds. When they arrived, he painstakingly sanded their barbs off under a microscope. Each quill has hundreds of barbs and Cho removed them all with folded sandpaper, taking care not to reduce the quill’s own diameter.

By shoving both shaved and unshaved barbs into pig skin, Cho showed that the barbs halve the penetration force needed to impale the meat. The barbed quills also slide in with less force than a hypodermic needle of the same width, or than the quill of an African porcupine, which doesn’t have any barbs (see end of post). They also penetrate deeper with the same amount of force, and cause less tissue damage.

“This was quite surprising to us,” says Karp. He suspects that the barbs are acting like the serrated edges of a knife, concentrating forces at small points in the surrounding tissue. Think about how much easier it is to cut a tomato with a serrated blade than a flat one.

Cho also found that the barbs increase the force needed to remove the quill by four times. As the quills are pulled out, the barbs flare out and bend, snagging onto tissue fibres. When Cho created replica quills with barbs that couldn’t bend, they took less effort to remove.

Once the team had sussed out the quills’ secrets, they duplicated them by creating artificial versions — barbs and all — from a plastic polymer. These have all the same properties as the natural ones, and Karp sees many uses for them. For a start, they could be used as a replacement for surgical staples. “Staples typically need to penetrate into the tissue to great depth, and need to bend to grip onto the tissue,” says Karp. “The quills don’t need that to stick, and they could do a lot less tissue damage when removed.”

They could also be used for any device that stabs into flesh, from needles, to tissue tunnellers used in bypass operations, to the meshes used to repair hernias. “The more force you need to apply to them, the less tactile feedback you get,” says Karp. If a quill-inspired needle could be jabbed in more easily, surgeons might be able to place them more accurately.

Of course, you would then have to get those devices out again, and barbed porcupine quills would make that more difficult. So Karp’s team is now developing quills with degradable barbs, which could stick for a specified amount of time before being easily removed.

P.S. So, why don’t African porcupines have barbs on their quills? “We’re not entirely sure although we have some assumptions,” says Karp. He wonders if African predators, like lions and leopards, are more aggressive than North American ones. Perhaps they’re more likely to run face-first into the spines? Alternatively, African porcupines are larger than North American ones, and have longer quills — maybe, that makes a difference.

Reference: Cho, Ankrum, Guo, Chester, Yang, Kashyap, Campbell, Wood, Rijal, Karnik, Langer & Karp. 2012. Microstructured barbs on the North American porcupine quill enable easy tissue penetration and difficult removal. PNAS http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1216441109