Around 3,000 years ago, people were going about their business in a marshy corner of eastern England known as The Fens.

These Fenland folk had just built their settlement over a slow-moving river channel, sinking wooden stilts for homes deep into the squishy soil. They had erected a wooden palisade around it all, creating as comfortable a gated community as one might imagine possible in a setting that was, well, a bit swampy.

Then, one day, less than a year after construction, fire consumed the entire settlement. The homes, the stilts and the palisade burned and quickly collapsed into the river. Of course, as soon as the flames hit the water, they fizzled out.

It was a terrible event for the people who lived there, and likely fled with little more than the clothes on their backs. But the settlement’s collapse, and subsequent burial in layers of silt, would be a gift to modern archaeology, preserving an incredible wealth of detail about how the fen folk lived.

Known today as Must Farm, and sometimes called Britain’s Pompeii, the doomed Late Bronze Age settlement has opened an unprecedented window into the past in the two decades since its discovery. While researchers will be combing through and analyzing finds for years to come, they’ve already identified a great deal, including well-preserved textiles, a bowl still holding a half-eaten meal (likely abandoned as the fire broke out), and, well, poop.

Don’t turn up your nose: Coprolites, or ancient feces, are some of the most valuable tools available for understanding how people and animals lived. And thanks to multiple samples from both humans and canines who lived at Must Farm, researchers are developing an idea of what they ate and how they lived. We are also learning how they stood out, at least parasitically speaking, from their neighbors.

Different Parasite Profiles

A previous study of ancient poop preserved at a Bronze Age farm in southwestern England revealed residents there were infected with both roundworm and whipworm, which spread through food contaminated with human feces.

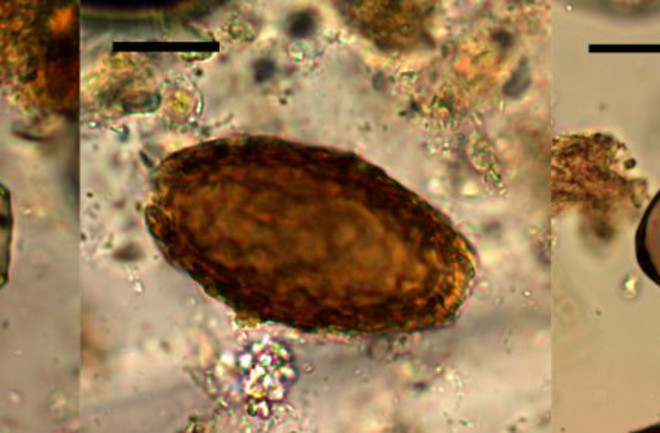

The fen folk were afflicted with different digestive hangers-on, however. The Must Farm team turned up the eggs of both fish tapeworms and giant kidney worms in fecal material collected from the site. Both parasites can be ingested by eating raw or undercooked aquatic animals, such as fish, frogs and mollusks.

While fish tapeworms stay in the gut, where they can grow to more than 30 feet in length, giant kidney worms, as their name suggests, take up residence in the kidney, destroying the organ as they grow to more than three feet in length.

The team also identified eggs of the Echinostoma worm. It’s perhaps not quite as nightmarish as the others, but it can still cause intestinal lining inflammation. Even less threatening, the researchers’ analysis turned up evidence of pig whipworm and Capillaria worm, both likely from eating land animals, though it’s unclear whether they were domesticated or wild. Neither parasite poses a particular threat to humans.

Several of the parasites identified, including the ghastly fish tapeworm and giant kidney worm, are the earliest examples of the animals infecting humans in Britain, according to the research team.

Interestingly, some of the soggy stuff the team analyzed turned out to be fecal matter from dogs rather than humans. The two species shared similar parasite profiles, suggesting that dogs were eating scraps of human food, or perhaps even shared their meals.

The researchers believe that living over a slow-moving river protected Must Farm’s Bronze Age inhabitants from some of the parasites plaguing their dry-ground neighbors — but also made them vulnerable to other critters looking for a host.

The study appears today in Parasitology.