By studying variations in tree rings in forests around the world, Neil Pederson and colleagues at the Tree Ring Laboratory at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York have created a record of droughts and wet periods dating back hundreds to thousands of years.

In 2010, while researching the effects of climate change over the past 20 years in Mongolia, his team serendipitously stumbled across a stand of pines that has since revealed the longest-ever climate record in the region. Data from that trip — and another in 2012 — tell a 1,100-year story of rainfall in a land where water is often scarce, and where rain might have meant more vegetation, more herd animals and more meat, milk and cheese.

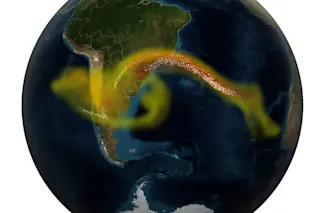

Now, Pederson and his colleagues are discovering that the wettest period in the country’s history, indicated by the widest series of tree rings, coincides precisely with warrior Chinggis (familiar to the West as Genghis) Khan’s rise to power. Rain may have provided just the fuel Khan and his troops needed to create the largest land empire in human history.

Each core sample is the width of a chopstick, and it could include hundreds of rings. Courtesy Neil Pederson/Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory/Columbia University

In his own words...

To get records of moisture, we cross-date different trees … and match patterns of large and small rings through time. It’s like a barcode of growth. So we can take a living tree back to the 1500s, and we can take trees that maybe died in the 1800s that might have lived for 500 years, and we can start going much further back in time than we would by looking only at the living trees. Our lab had been working in Mongolia since the mid-’90s; of the collections the tree-ring lab had done there that gave moisture information, the longest was 663 years.

In 2010, we went to Mongolia for a month, but in actuality we only had 10 to 15 days in the field, during which time we hoped to study the impact of climate change on wildfires in some of the country’s larch forests. It was a tight schedule. We were driving by this lava field when [West Virginia University collaborator] Amy Hessl said, “What’s that?” I said, “That’s the Khorgo lava field,” and she said, “We really should sample that. There’s a good chance we could get a long record.” So we made time in the schedule.

We were at the lava fields for two days. At one point, I saw a dead Siberian pine with this beautiful, complex architecture that showed signs of great age.

One of my pet hobbies is identifying old trees by their external characteristics. These Siberian pines are very bulbous — you can see there’s been dieback on certain parts of the trunk, and then you can see there’s regrowth. They almost look like inverted carrots — they’re much wider at the base, and they’re usually big and twisty and gnarled. So when I saw this tree, I just really got excited; if we found one, maybe there were more.

This cross section of a Siberian pine, with its 799 rings, stretches back to the period before Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire. Courtesy Neil Pederson/Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory/Columbia University

In Mongolia, dead trees can be preserved for hundreds of years because it’s so cold and dry. But they’re usually not around for us to study. Wood is valuable in that country, so when a dead tree falls, it’s usually utilized or burned in fires. So it wasn’t what we were expecting to see; it was just a great, surprising gift.

Because these pines were really an afterthought, we made only a quick collection and sampled just 18 trees: seven dead and 11 living ones. From that very, very small collection of pine, I was thinking we’d be able to compile a reliable record going back 700 years, maybe 800. But from the edge to the center of one [cross section] there were 800 rings. When this record was combined with the other tree samples, we went back about 1,100 years in all — that was really astounding. This is the first tree-ring record that is providing a climatic context for some of the great changes in Asian and world history.

[This article originally appeared in print as "Reading the Trees."]