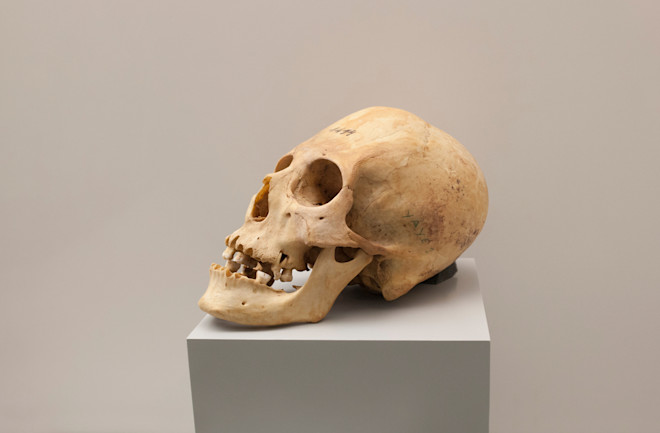

From foot binding and scarification to dental alignment and ear piercings, the practice of modifying one’s body — usually for religious or aesthetic purposes — has followed us since the dawn of humankind. In fact, a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology described noticeable dental abrasions and other oral anomalies on the skull of an archaic human specimen.

History provides many examples of permanent body alterations — among the most famous are the foot binding of women in traditional China and the insertion of lip plates employed by the Mursi people of Ethiopia. Another striking form of body modification called artificial cranial deformation has been adopted throughout our history and long fascinated researchers.

What Is Artificial Cranial Deformation?

Artificial cranial deformation (ACD) is the intentional manipulation of the skull's physical attributes, and is usually practiced on infants and facilitated by caregivers.

The desired shape is typically achieved through head binding or flattening. Although it has been utilized by groups throughout the world, the Maya people pioneered this technique by introducing a distinctive head-flattening apparatus — sometimes appearing similar to a cradleboard — that was affixed to the child's skull. Over time, the head shape would become elongated and conical due to the constant pressure exerted on the developing cranium. The Maya may have intended to protect young people’s souls and prevent injury from “evil winds.”

In what is now Peru, the Paracas civilization — estimated to have existed between 750 B.C. and A.D. 100 — deployed a different strategy, tightly wrapping the head in cloth to elongate or deform the cranium. In the 1920s, Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello, who established himself as the "father of Peruvian archaeology," uncovered hundreds of elongated skulls from Paracas, some with partially attached scalps and hair.

These artifacts remain on display at various science and cultural museums around Peru and have become the subject of online controversy among UFO enthusiasts and paranormalists who proclaim that they are of extraterrestrial origin and belong to "gray aliens."

Status Symbols

Since Julio Tello’s intriguing findings, scientists have sought out the motivations behind such practices. From a modern Western perspective, the elongation or artificial deformation of the skull may appear unusual. But for the groups that practiced it in ancient times — and in some cases up to this day — elongated and intentionally shaped craniums symbolize beauty and status.

They may also have denoted belonging. Marta Alfonso-Durruty, an anthropologist at Kansas State University, affirmed this hypothesis: She and her colleagues examined 60 adult skulls recovered from Southern Patagonia and areas of Tierra del Fuego, belonging to a group of hunter-gatherers who lived 2,000 years ago. The team noted in a 2015 Journal for Physical Anthropology study that many had elongated skulls, and explained that body modification was probably intended in this context to form a sense of unity and identify outsiders.

The Maya took a similar approach, and likely used ACD to discern members of nobility, such as the children of priests and high-ranking individuals, from others. The Mangbetu people, who currently live in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo, also used a cloth to tightly bind the heads of female children, beginning a month after birth, in a cultural tradition called Lipombo. The Mangbetu shared similar sentiments to other groups around the world, regarding the women's elongated heads as a status symbol denoting attractiveness and intelligence — though the use of ACD in this context has become less common since the 1950s due to Belgian colonial influence.

Current Practices

ACD is still performed worldwide for both hierarchical and religious reasons. In recent history, various communities in Eurasia — including in Scandinavia, Britain, and Eastern Europe — have practiced artificial cranial deformation. Notably, in Toulouse, France, individuals of lower economic status used bands and cloths to intentionally deform their children’s heads, similar to the Paracas people, a process that usually required between three and four months to complete. This French practice, called the “Toulouse deformity” or bandeau, was utilized in various parts of France and was recorded as recently as the early 20th century in the region of Deux-Sèvres in western France.

ACD lives on elsewhere: For example, in Vanuatu, a Pacific island nation, locals on the southern island of Malakula bind their heads to resemble the cultural deity Ambat, who is said to have had an elongated cranium and long, defined nose. “We elongate the heads of our children because it is our tradition, and it originates with the basic spiritual beliefs of our people,” said the General of South Malakulan, according to the Australian Museum website. “We also see that those with elongated heads are more handsome or beautiful, and such long heads also indicate wisdom.”

Debates Over Health Risks

Some experts studying the ancient usage of ACD claim they haven’t found significant evidence of health risks, while others argue the opposite. A 2003 research article published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology concluded that, although the practice causes substantial changes in the aesthetic features and shape of the face and skull, "differences between deformed and undeformed crania are generally not related to differences in overall cranial size."

But another review from 2013 suggested that the deformation of the cranium’s attributes was profound and negatively impacted the brain's various lobes, promoting cognitive impairments such as concentration and memory issues, visual and motor impairments, and the possible onset of behavioral disorders. It’s difficult to say for sure how ACD affected people when it was more prevalent, but researchers could draw similarities between the outcomes of intentional deformations versus conditions such as plagiocephaly and craniosynostosis.