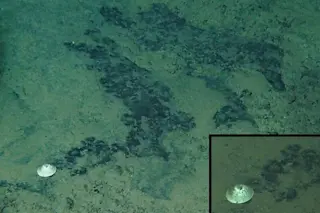

The Great Apes Edge Toward Extinction

The finding was bad enough: During the last two decades, the population of wild chimpanzees and gorillas in the West African nations of Gabon and the Republic of the Congo has declined by more than half. But it was the context that made the news so discouraging. The dense forests in the two nations harbor an estimated 80 percent of the world’s remaining great apes, whose numbers have plunged elsewhere in Africa as human populations have expanded.

What’s more, scientists and conservationists have been active in the area for many years. “The fact that all of this could go on before our eyes and we didn’t see it happening is the really scary thing,” says Lee White, a Wildlife Conservation Society ecologist and coauthor of a study published in April that sounds a dire warning. Without aggressive intervention, wild chimps and gorillas could be ...