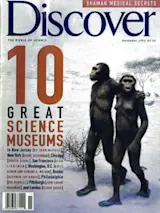

Early hominids may have stood up and gotten naked as a way to cope with heat stress on the sere African savanna.

Human beings are a peculiar species. Among other things, we’re the only mostly hairless, consistently bipedal primate. Ever since Darwin, evolutionary biologists have wondered how we acquired these unique traits. Not long ago most would have argued that our upright stance evolved as part of a feedback loop that helped free our hands to use tools. But by the early 1980s a series of discoveries in Africa--including fossilized footprints and early hominid bones--made it clear that bipedalism preceded tool use by at least 2 million years. Lately a new theory has been gaining ground: it holds that our forebears reared up on two legs to escape the heat of the African savanna.

The African savanna is one of the most thermally stressing habitats on the planet as far as large mammals are concerned, says Pete Wheeler, a physiologist at Liverpool John Moores University in England. For several years now Wheeler has been studying just how stressful such an environment would have been for the first primates to venture out of the shade of the forest. Among the apes, our ancestors are the only ones that managed the switch; no other ape today lives on the savanna full-time.

Most savanna animals, says Wheeler, cope with the heat by simply letting their body temperature rise during the day, rather than waste scarce water by sweating. (Some antelope allow their body temperature to climb above 110 degrees.) These animals have evolved elaborate ways of protecting the brain’s delicate neural circuitry from overheating. Antelope, for instance, allow venous blood to cool in their large muzzles (the cooling results from water evaporation in the mucous lining), then run that cool blood by the arteries that supply the brain, thereby cooling it too.

But the interesting thing about humans and other primates, says Wheeler, is that we lack the mechanisms other savanna animals have. The only way an ape wanting to colonize the savanna could protect its brain is by actually keeping the whole body cool. We can’t uncouple brain temperature from the rest of the body, the way an antelope does, so we’ve got to prevent any damaging elevations in body temperature. And of course the problem is even more acute for an ape, because in general, the larger and more complex the brain, the more easily it is damaged. So there were incredible selective pressures on early hominids favoring adaptations that would reduce thermal stress--pressures that may have favored bipedalism.

Just how would bipedalism have protected the brain from heat? And why did our ancestors become bipedal rather than evolve some other way to keep cool? Before moving out onto the savanna, says Wheeler, our forebears were preadapted to evolve into bipeds. Swinging from branch to branch in the trees, they had already evolved a body plan that could, under the right environmental pressures, be altered to accommodate an upright stance. Such a posture, says Wheeler, greatly reduces the amount of the body’s surface area that is directly exposed to the intense midday sun. It thereby reduces the amount of heat the body absorbs.

Although this observation is not new, Wheeler has done the first careful measurements and calculations of the advantages such a stance would have offered the early hominids. His measurements were rather simple. He took a one-foot-tall scale model of a hominid similar to Lucy--the 3- million-year-old chimp-size australopithecine that is known from the structure of her pelvis and legs to have been at least a part-time biped. Wheeler mounted a camera on an overhead track and moved it in a semicircular arc above the model, mimicking the daily path of the sun. Every five degrees along that path--the equivalent of 20 minutes on a summer day--Wheeler stopped the camera and snapped a photograph of the model. He repeated this process with the model in a variety of postures, both quadrupedal and bipedal.

To determine how much of the hominid’s surface area would have been exposed to the sun’s rays, Wheeler simply measured how much of the model’s surface area was visible in the sun’s-eye-view photos. He found that a quadrupedal stance would have exposed the hominid to about 60 percent more solar radiation than a bipedal one.

Not only does a biped expose less of its body to the sun, it also exposes more of its body to the cooler breezes a few feet above ground. The bottom line, says Wheeler, is that on a typical savanna day, a knuckle- walking chimp-size hominid would require something in the region of five pints of water a day. Whereas simply by standing upright you cut that to something like three pints. In addition to that, you can also remain out in the open away from shade for longer, and at higher temperatures. So for an animal that was foraging for scattered resources in these habitats, bipedalism is really an excellent mode of locomotion.

Wheeler suspects that bipedalism also made possible two other uniquely human traits: our naked skin and large brains. Our work suggests that you can’t get a naked skin until you’ve become bipedal, he says.

The problem has always been explaining why we don’t see naked antelope or cheetahs. The answer appears to be that in those conditions in which animals are exposed to high radiation loads, the body hair acts as a shield. We always think of body hair as keeping heat in, but it also keeps heat out. If you take the fleece off a sheep and stand the animal out in the desert in the outback of Australia, the sheep will end up gaining more heat than you’re helping it to dissipate. However, if you do that to a bipedal ape, because the exposure to solar radiation is so much less, it helps the ape lose more heat. Bipedalism, by reducing exposure to the sun, is tipping the balance and turning hair loss, which in quadrupeds would be a disadvantage, into an asset.

We bipeds maximize our heat loss, says Wheeler, by retaining a heat shield only on our most exposed surface--the top of our skull--and by exposing the rest of our body to cooling breezes. And bipedalism and naked skin together, he says, probably allowed us to evolve our oversize brains.

The brain is one of the most metabolically active tissues in the body, he explains. In the case of humans it accounts for something like 20 percent of total energy consumption. So you’ve got an organ producing a lot of heat that you’ve got to dump. Once we’d become bipedal and naked and achieved this ability to dump heat, that may have allowed the expansion of the brain that took place later in human evolution. It didn’t cause it, but you can’t have a large brain unless you can cool it.