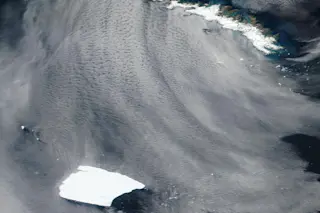

Antarctic krill, small shrimplike creatures, swim in dense schools of 20,000 or so animals per cubic yard. To avoid turbulence they adopt a staggered formation so that no krill swims directly in another’s wake. That obviously requires some kind of coordination. Konrad Wiese, a zoologist at the University of Hamburg, thinks he’s figured out how krill keep in touch: their tiny antennae pick up pressure waves from their neighbors. Wiese glued a tiny Lucite block to a krill to immobilize it, as shown here, and placed a small pressure sensor near the swimmerets--the bristle-covered legs that propel the animal. He detected four distinct signals: a low-frequency wave coming from the paddling swimmerets themselves and three higher-frequency signals from the bristles, which increase the surface area of the swimmerets by folding and unfolding as the krill swims. The low-frequency wave, Wiese thinks, tells each krill how fast the krill ahead is ...

The Krill Drill

Discover how Antarctic krill use pressure waves communication to maintain coordination in dense schools while swimming.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe