It has been quiet at Kīlauea in Hawaii. The eruption on the lower East Rift Zone that captured the planet’s attention over the summer trickled to a stop in late August and since then there hasn’t been much going on at all at the giant shield volcano. In fact, the Hawaii Volcano Observatory reports that carbon dioxide emissions at Kīlauea are lower than anything they’ve seen in over a decade. Earthquakes and collapses are now infrequent on the volcano and nary a lava flow can be seen at the surface, even deep in the Fissure 8 cinder cone built on the site of Leilani Estates. Even the ubiquitous deformation that was happening at the summit (deflation) and in the lower East Rift Zone (inflation) have vanished. Hawaii Volcanoes National Park reopened to tourists this past week after closing the whole summit of Kīlauea. By no means is anyone declaring the eruption over, but right now, Kīlauea really not doing much.

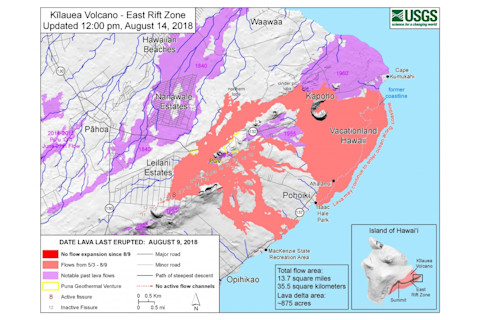

So, let’s take stock in what happened during the eruption. Here’s some of the data: approximately 35.5 square kilometers of the big island were repaved with lava, which includes ~3.5 square kilometers added to the island. That’s roughly twice the size of Key West in Florida but only 0.3% of the area of the island of Hawaii itself.

A rough estimate of the total volume erupted is 0.5 cubic kilometers, putting it at about half the size of the 2014-15 Holuhraun eruption in Iceland but amongst the largest in recorded history from Kīlauea (which is the last ~250 years). However, that is still enough to coat the entire island of Manhattan with ~8.5 meters (~27 feet) of lava. Although the number is still not certain, likely over 700 homes were destroyedalong with other structures across the area from Leilani Estates to Vacationland Hawaii, where the lava filled in Kapoho Bay entirely.

USGS map showing the extent of the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption from Kīlauea. USGS/HVO.

USGS map showing the extent of the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption from Kīlauea. USGS/HVO.

With the eruption ceased at Fissure 8, the USGS was able to take a closer look at the new cone on Kīlauea with a drone (see above). In the video that it took, you can really see the walls of spatter that built the cone with the now solidified lava lake in the middle. This is where the lava flows that eventually made it to the Pacific emanated. Right now, weak steam plumes are the only sign that 3 months ago lava fountains hundreds of meters into the sky.

This image (below) is an overlay of a before shot of the area and a recent Planet image of the results from the eruption taken on September 9. You can clearly see just how much of Leilani Estates and Vacationland Hawaii was covered by lava (see the map above for a guide to the image).

LERZ_BeforeAfter

In this scene from the Planet image, I marked some important sites from the eruption. You can see how lucky the Pahoa Geothermal Venture was as two lava flows moved around the plant. Fissure 8 is marked, along with the long lava channel that developed that helped carry lava to the Pacific through a mix of surface channels and lava tubes. You can also see where Highway 132 was covered with lava flows.

Close view of the Leilani Estates area on September 9, 2018. Planet, image used by permission.

Close view of the Leilani Estates area on September 9, 2018. Planet, image used by permission.

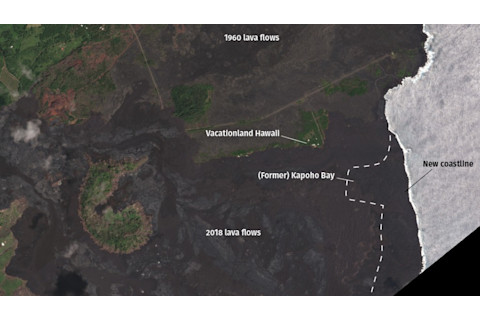

On this scene, I marked the approximate location of Kapoho Bay that was buried by lava. The old coastline is now hundreds of meters inland and much of Vacationland Hawaii is now under a thick layer of lava. If you want to get a feel for how long it might take for the area to recover, just to the north (above) the 2018 lava flows are 1960 lava flows that covered the lower East Rift Zone. They don’t look too different beyond a slightly more reddish color associated with weathering due to rain.

The former site of Kapoho Bay, covered by 2018 lava flows. Seen on September 9, 2018. Planet, image used by permission.

The former site of Kapoho Bay, covered by 2018 lava flows. Seen on September 9, 2018. Planet, image used by permission.

Right now, the biggest question for geologists is what is Kīlauea going to do next. The volcano had 35 years of nearly constant activity at Pu’u O’o and the summit, but now, after this lower East Rift Zone eruption, everything has stopped. Will Kīlauea continue to erupt on the lower East Rift Zone around where the Leilani Estates eruption occurred? Will it reestablish the lava lakes at the summit and Pu’u O’o? That seems unlikely considering the collapses that occurred at both. So, have we entered a new phase of activity for Kīlauea? The low carbon dioxide emissions and lack of inflation suggest that there isn’t much new magma coming into the system, but as we’ve seen, this can change quickly.

This is more than an academic question as the people who used to live in the now-buried areas of the lower East Rift Zone will need to decide if they want to try to rebuild like people have done at Kalapana or whether they try to move to a less volcanically-active place. Home sales have already been impacted by the eruption. The government could intercede to make it more difficult to develop in places prone to volcanic eruptions, however economic pressures in Hawaii make this unlike. Right now, only time will tell what might happen next at Kīlauea, but the ramifications of the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption will be felt for decades to come.