2018 was a blockbuster year for genomes in archaeology. Researchers reported ancient DNA (aDNA) from over 1,400 human remains, more than doubling the number of individuals who have yielded ancient genomic data. Many of the sequences have come from Europe and other regions with temperate climates, but researchers also recovered samples from environments long considered too hot and humid for aDNA preservation.

The surge in aDNA data is due to cheaper, faster methods for reading genetic code, as well as the discovery three years ago that the dense petrous bone of the inner ear can preserve up to 100 times more aDNA than other skeletal parts. It’s a “big game changer ... this little vault of aDNA,” says Elizabeth Sawchuk, a postdoctoral archaeologist at Stony Brook University.

The volume of genomic data analyzed enabled researchers to test some big hypotheses, including scenarios for the first migrations of people to the Americas and the spread of Indo-European language speakers. Along the way, intimate aspects of our ancestors have been revealed, such as skin color and the diseases they sometimes had to endure.

Early Americans

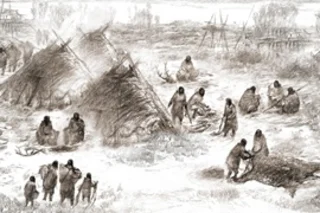

Around 11,500 years ago in the Tanana River Basin in central Alaska, bodies of two infants were covered in red pigment and buried in a grave. The babies belonged to a previously unknown, genetically distinct group of Native Americans, according to an analysis in Nature in January. About 20,000 years ago, as people were migrating across the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska, this population branched off from the others and eventually moved into the northern part of North America.

Other people who crossed the bridge at this time continued south, deep into the Americas. This migrating group split into two distinct populations between 14,600 and 17,500 years ago, and later reunited en route to South America, according to a separate study published in Science in June. The researchers analyzed 91 genomes, mainly from California’s Channel Islands and Ontario, Canada, making it the largest aDNA study so far in the Americas.

Iceland’s Past and Present

Iceland was settled roughly 1,000 years ago by Vikings and their slaves. As might be expected, the genomes of 27 of these early inhabitants showed mixed Gaelic and Norse ancestry, according to a June Science paper. Modern Icelanders are largely genetically distinct from their distant Viking ancestors, however. The new study suggests the DNA disparity, not uncommon in small island populations, is a clear case of genetic drift: Chance determined which genes got passed to subsequent generations. Social factors, such as selective mating based on status, also may have played a role.

At more than 1,000 years old, remains of the first Icelanders, such as this skeleton, are genetically distinct from the island nation’s modern population. (Credit: Ivar Brynjolfsson/The National Museum of Iceland)

Ivar Brynjolfsson/The National Museum of Iceland

The Steppe Highway

The Eurasian steppes — thousands of miles of grassland between Hungary and China — have been the scene of human migrations for millennia. The genomes of 211 individuals who lived there between 500 and 11,000 years ago were published by geneticists in Nature in May and in Sciencein June. Some of the discoveries: Hunter-gatherers with no genetic ties to nearby farmers likely domesticated horses 5,000 years ago in Kazakhstan; Scythian nomads who ruled the steppe during the first millennium B.C. had genetically diverse ancestries; and an 1,800-year-old Hun from Kyrgyzstan harbored flea-borne bubonic plague, suggesting the pathogen spread to Europe along the Silk Road, a vast network of trade routes across Europe and Asia.

A bronze statuette of a mounted archer, about 2,500 years old, is an artifact of the genetically diverse Scythian culture. (Credit: Artokoloro Quint Lox Limited/Alamy Stock Photo)

Artokoloro Quint Lox Limited/Alamy Stock Photo

Africa's New Frontier

Researchers have sequenced the oldest human aDNA so far recovered in Africa. Excavated at a burial site in Morocco, seven 15,000-year-old skeletons showed genetic ties to ancient Near Easterners and modern sub-Saharan Africans, proving there was interaction across the desert among human groups, researchers reported in Science in May.

Technological advances and the knowledge that a skull’s petrous bone sometimes preserves aDNA even in arid climates has researchers scrambling to Africa. One of the largest projects has sampled skeletal remains from collections in Tanzania, Zambia and Kenya. The material currently is being sequenced at Harvard Medical School.

Louise Humphrey, left, of the Natural History Museum in London, was part of the international team that excavated seven ancient skeletons in Morocco. At right is a skull fragment from one of the individuals. (Credit: Ian R. Cartwright/Institute of Archaeology Oxford University)

Ian R. Cartwright/Institute of Archaeology Oxford University