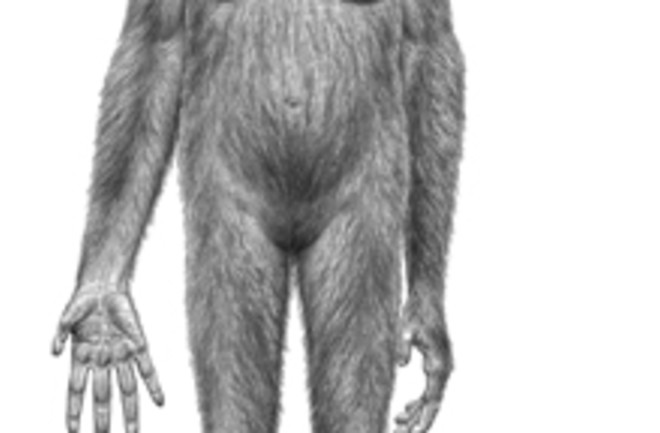

The bones of our ancestors do not speak across time with ultimate clarity. The fossils with which scientists reconstruct our family tree are often fragments that offer hints and clues to where we came from. So it comes as no surprise when, as part of the flow of science, researchers offer counter-interpretations to even the most famous of finds. That's what happening to Ardi. Last October Ardipithecus ramidus hit the main stage when, after 17 years of study, a large team led by paleoanthropologist Tim White published its work in the journal Science. The 4.4-million-year-old find shakes up our understanding of our own history, White said—primarily the story of how and when we learned to walk. Ardi cast doubt on the widely accepted view that our ancestors became bipeds because they left the forest and entered a flatland savanna habitat that demanded it. But Ardi appeared to be a kind of hybrid, comfortable in the trees and on the ground. And, White said, analysis of the site where the fossil was found indicated that Ardi lived in a woodland habitat. If it's true that early humans walked in the woods, then the "savanna hypothesis" would be swept away. But not so fast. In today's edition of Science, two teams of scientists respond (1, 2) with doubts about the story of Ardi.

The question of Ardi’s habitat was raised by Thure E. Cerling, a geochemist at the University of Utah, and seven other geologists and anthropologists. They said they used the White team’s own data for soils and silica from ancient plants, and found it did not support an interpretation that Ardi lived in thick woods. Instead, Dr. Cerling’s group said, “We find the environmental context of Ar. ramidus at Aramis to be represented by what is commonly referred to as tree- or bush-savanna, with 25 percent or less woody canopy cover” [The New York Times].

The second paper questions whether Ardi is really an early human at all, rather than a member of the chimpanzee line.

Ardi's age is so close to that divergence date that no unequivocal determination can be made about whether she is in the ape or human lineage, says [primatologist Esteban] Sarmiento, who conducts research from home in East Brunswick, New Jersey. But White and co-authors disagree. In their response, the group says Sarmiento's "tortuous, nonparsimonius evolutionary pathways" are not supported by many of the fossil's characteristics [Nature]. White and colleagues issued responses to both questions (1, 2) in the same issue, and struck back in the press, too.

If Ardi were really ancestral to chimps, certain features of its teeth, pelvis, and skull would have had to later evolve back to their more ape-like conditions, an "evolutionary reversal that's highly unlikely," White said in an interview [AP].

White is sticking to his guns regarding Ardi's habitat, too. While it's true that the fossil record seems to show grasses where Ardi lived, there are also many fossils of forest-dwelling animals that suggest a wooded area, he argues. Related Content: The Loom: Ardipithecus: We Meet at Last

DISCOVER: Meet Ardi, Your First Human Ancestor

DISCOVER: The 2% Difference

examines what sets us apart from chimpanzees 80beats: A Fossil Named Ardi Shakes Up Humanity's Family Tree

80beats: No Tarzans Here: Earliest Humans Quickly Lost Their Ape-Like Climbing Abilities

Image: J.H. Matternes