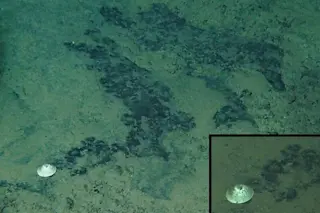

When a dead whale turns up in False Bay, on the South African coast, guess who’s coming to dinner? The answer surprised even the researchers studying the feeding event. In a study

published in the open-access journal PLOS One, researchers observing False Bay’s famous great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) observed that scavenging events changed the sharks’ behavior markedly---and attracted much larger sharks than typically seen in the area. The findings are important because little is known about how or how often sharks scavenge, though scientists hypothesize that scavenging is a crucial activity for the apex predator. False Bay has become internationally known for its sharks thanks to the population's density and high-profile media coverage of some of them leaping out of the water to catch seals. The famous airborne sharks of the area, according to the study, are typically 9-12 feet in length. On four separate scavenging occasions, however, researchers noted that whale carcasses attracted several sharks up to 18 feet in length. Many of the larger individuals had not been previously observed by the team, which has been conducting research in the area since 1997 and has identified and tagged scores of sharks during that time. Observation of the scavenging events found the sharks methodically eating first the whale’s fluke and then the most blubber-rich areas of the carcass, sometimes regurgitating one bite to make room for a second, more calorically-rich morsel. This pattern is further evidence that white sharks are adept at assessing the caloric value of their food and are selective when feeding. During one scavenging event, for example, a 13-foot-long shark was observed moving into the carcass to reach and remove a near-term fetus from the dead whale’s uterus, which it then consumed. Because C. carcharias lacks the protective nictating membrane some other sharks have, it typically rolls its eyes back in their sockets at the moment of attack to avoid being injured or even blinded by struggling prey, a behavior known as ocular rotation. Researchers at the whale carcass events, however, did not observe any ocular rotation among the sharks feeding. Perhaps even more surprising, despite the number of sharks feeding at the same time---even bumping into each other, according to researchers---there were no displays of aggression or “feeding frenzy” behaviors. At various times during one scavenging event, for example, three or more large sharks (approximately 16 feet long) fed “belly-up next to each other…with their pectoral fins overlapping,” without incident, according to the study. The team documented the four separate scavenging events as part of its long-term study of the False Bay population. When a whale carcass was noted in the area, researchers anchored their boat alongside the carcass to better observe the sharks’ behavior and estimate the size of the predators feeding. The study’s findings are particularly important because, despite its ubiquitous presence in pop culture, many aspects of C. carcharias’ behavior remain a mystery. Being able to observe the apex predator’s scavenging of whale carcasses is a particularly rare event: According to the study, since 1896 only 19 such events have been recorded in scientific literature, and only two of those studies focused specifically on the sharks’ behavior. http://vimeo.com/63683277 Image courtesy Fallows, et al., PLOS ONE