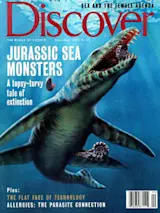

One hundred sixty million years ago, an elegant sea monster lay down on its right side and died on the warm, muddy ocean bottom near the present-day town of Lookout, Wyoming. As the creature’s 14-foot-long body was convulsed by one last set of involuntary muscle contractions, its powerful sharklike tail twitched and stirred the bottom mud. A faint trail of bubbles escaped from the corner of its mouth and rose 300 feet to the surface, where tropical sunshine was playing on the waves. Then a bottom current gave the beast a decent burial under a blanket of pale green sand, part of the accumulating sediment layers that would become known as the Redwater Shale Member of the Sundance Formation.

Usually the events leading up to any one individual death in geologic time are obscured, the details lost, the exact time of day not recorded by any sign preserved in the ...