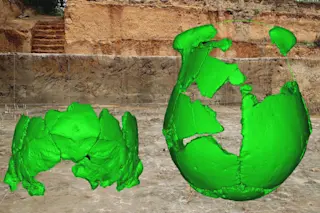

Leprechaun skulls! Kidding. The vivid green chosen for this reconstruction of two partial human crania sure does help them stand out from the background, a photograph of the site in China where they were found. Credit: Xiujie Wu. The period about 100,000 years ago was a crucial one for our species — and a time not well represented in the fossil record. A pair of partial human skulls from Central China are helping to fill in some of the mystery, but their blend of archaic and modern Homo sapiens traits, as well as some Neanderthal characteristics, are also raising new questions. We modern Homo sapiens are, biologically speaking, true new kids on the block. Paleoanthropologists conventionally put the date of our emergence as a species at less than 200,000 years ago, in Africa. By that time, multiple other members of our genus had already explored much of Eurasia, from Neanderthals ...

Human Skull Fossils from China Have Surprising Traits

Discover the significance of two partial human skulls, Xuchang 1 and 2, in understanding human evolution. Unique traits abound!

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe