For decades, schoolchildren across the globe were taught our origin story went something like this: An archaic form of Homo sapiens evolved around 200,000 years ago in Africa. By about 100,000 years ago, the population had become anatomically modern humans who, around 50,000 years ago, headed across Eurasia and met up with our distant cousins the Neanderthals (and the closely related Denisovans, not known to science until 2010).

Like a game of Jenga, however, researchers have recently been removing bricks and destabilizing that towering timeline. In 2017, a few more bricks came out, and the conventional chronology of our origins finally toppled.

What we’re left with: Homo sapiens have been around at least 100,000 years longer than we thought, and left Africa much earlier than we believed. And whenever they ran into other hominin populations, well . . .

“Sex happens,” says Erik Trinkaus, a paleoanthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis. “You can draw lines of different lineages on maps, but real populations don’t behave that way.”

Trinkaus stresses that revising the timeline for human evolution isn’t the same as starting from scratch: “The differences are of refinement, not in the basic story.”

In the mid-20th century, during mining operations at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, workers turned up some old, possibly human bones. The haphazard find made dating them confidently all but impossible.

Paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin and colleagues returned to the site recently to excavate an area undisturbed by mining. They hoped to find material that could help them date the earlier discovery.

Instead, they found what Hublin calls “a big wow”: the partial remains of at least five humans, plus tools and other artifacts, most of which are about 300,000 years old.

The archaic Homo sapiens’ facial features and brain volume are essentially modern, says Hublin, though their skulls’ shape is more primitive.

During a June news conference, shortly before the study was published in Nature, Hublin noted it’s unlikely the Jebel Irhoud individuals, the oldest known Homo sapiens fossils by about 100,000 years, are our direct ancestors.

“We are not claiming that Morocco became the cradle of modern humankind,” Hublin says, “We think early forms of humans were present all over Africa.”

And in the journal Science in late September, a separate team offered additional evidence of an earlier start date for our species: By sequencing the ancient DNA of seven individuals from southern Africa, the researchers determined modern Homo sapiens emerged up to 350,000 years ago.

For years, paleogenetic studies have been turning up hints that our species interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans between 40,000 and 100,000 years ago. A Nature Communications study published in July, however, found evidence the hook-ups began much earlier: roughly 220,000 to 470,000 years ago.

Researchers extracted maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from a 100,000-year-old Neanderthal bone found in a German cave in the 1930s. The mtDNA is from a Homo sapiens female who evolved in Africa — our homeland — and mated with a European-evolved Neanderthal at least 220,000 years ago.

But the woman, who passed her mtDNA down through the Neanderthal lineage, was not necessarily an anatomically modern human, notes paleogeneticist Johannes Krause, a co-author of the study. Although he agrees recent evidence pushes back the start date for our species, Krause said the definition of a modern Homo sapiens remains subjective.

“The process of humans evolving into anatomically modern humans started 700,000 years ago,” says Krause. That’s when genomic models estimate the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans existed. “It’s a gradual change. They didn’t pop out of a box.”

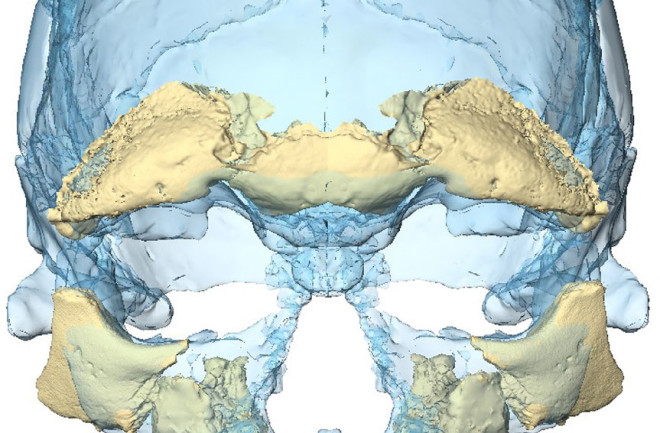

A pair of partial hominin skulls excavated in Xuchang, China, are unlike any others.

Dated to more than 100,000 years old, the crania have a unique blend of features: the internal ear structure and back-of-skull depression seen only in Neanderthals, which have never been found east of Siberia; a low and broad shape consistent with earlier East Asian hominins; and an enlarged braincase similar to other late archaic and modern humans.

Trinkaus and colleagues, describing the partial skulls in March in Science, won’t speculate on whether they belonged to Homo sapiens transitioning from archaic to modern, the elusive Denisovans or an as-yet-unidentifi ed hominin species.

“People have been thinking in terms of lineages and discrete groups,” Trinkaus says, “These are not separate entities. There’s a unity to humankind now, and there was then.”

The conventional timeline placed our species in Australia at no earlier than about 47,000 years ago, despite some archaeological and genomic research hinting at a much earlier arrival date. In July, however, a team reported in Nature that thousands of artifacts from a Northern Australia site were about 65,000 years old.

And in August, also in Nature, a separate team reported that they believe teeth found in an Indonesian cave belonged to anatomically modern humans who had occupied the site 63,000 to 73,000 years ago.

That puts modern humans far from home tens of millennia before the now-outdated human evolution and migration timeline had us even leaving Africa.

A Nature study published in April made a startling claim: Rounded stones found beside fractured mastodon bones near San Diego were evidence of someoneprocessing the animal’s remains 130,000 years ago.

The current timeline for humans arriving in the Americas, however, is a mere 15,000 to 20,000 years ago, via Siberia and the now-submerged land bridge Beringia. Many in the field are highly skeptical of the Nature paper.

“These are just naturally occurring rocks that, over time, have broken along existing fractures,” says Texas A&M University archaeologist Michael Waters. “The evidence for early human occupation is not there.”

Found during highway construction in 1992, the southern California site yielded the stones and mastodon bones, several of which were fractured or in unusual positions. But the items weren’t interpreted as evidence of hominin activity until recently, when they drew the interest of Steven Holen, lead author of the Nature paper.

“My first reaction was, ‘This is not possible,’ ” Holen says. His team took a multidisciplinary approach to analyzing the material, from sophisticated dating techniques to re-creating the kinds of fractures such stones might have made, using fresh elephant bones in Africa.

Holen argues fluctuating sea levels exposed Beringia 130,000 to 160,000 years ago, when bison crossed the land bridge into the Americas. It’s possible, he believes, that a population of hominins — Neanderthals, Denisovans or even archaic Homo sapiens — followed the animals.

Holen says he knew his paper would ignite controversy, and that he’d be the first to admit “you need to have more than one site if you’re going to have a paradigm shift.” He hopes more researchers will remain open-minded.

“The most important thing for a reader to take away from this, and also for young scientists in general, is that we don’t have all the answers,” Holen says. “That’s why we do science."