Stone tools, charcoal and other artifacts from Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, are the latest evidence that the First Americans arrived more than 16,000 years ago — well before an overland route existed. It’s looking more and more likely the first people arrived via a Pacific Coast route.

Few debates in archaeology get as heated as the arrival date — and route — of the first humans to reach the Americas.

For years, based on archaeological evidence, researchers believed the New World wasn’t populated until about 13,500 years ago. That’s when, the thinking went, glaciers receded and opened an ice-free corridor in what’s now Alaska and Canada. (Some estimates put the opening of the corridor as early as 14,800 years ago; others, a mere 11,500 years ago.) The ice shrinkage allowed game, and the humans hunting it, to move east and south from Beringia, a massive land bridge that connected Asia to North America during the last Ice Age.

While the Beringia overland route was the best hypothesis based on the evidence available back in the day, numerous discoveries in recent years are in direct conflict with this now outdated theory.

Just a few examples: Piles of projectile points and other artifacts from Texas suggest a well-established human presence in the region 15,500 years ago and perhaps as much as 20,000 years ago; a mastodon butchering site in Florida and human coprolites from Oregon are well over 14,000 years old; artifacts found at Monte Verde, Chile may be more than 18,000 years old.

What Lies Beneath

It’s looking more and more likely that the First Americans arrived from Beringia via a Pacific Coast route, also known as the Kelp Highway, centuries if not millennia before the inland ice-free corridor opened up.

Hard and fast evidence of the actual Pacific Coast route is hard to come by, however. Thanks to the sea level rise that followed the end of the last Ice Age, coastlines have moved considerably, sometimes by hundreds of miles. Any signs of human habitation along much of the coast are now deep underwater.

Although a number of ambitious research projects are underway to find these sites, often using maps and techniques developed for oil and gas exploration, the best bet for finding evidence of the First Americans remains on dry ground, in areas where the explorers moved inland as they spread across the continent.

An Ancient Village

And so we arrive at Cooper’s Ferry, along western Idaho’s Salmon River. The area’s Niimíipuu, or Nez Perce Tribe, have long considered the location to be home to an ancient village, and previous archaeological exploration, in the late 1990s, turned up artifacts that were more than 11,000 years old.

A more recent and intensive, decade-long dig uncovered hundreds of artifacts from several different periods, some significantly older than the previous finds.

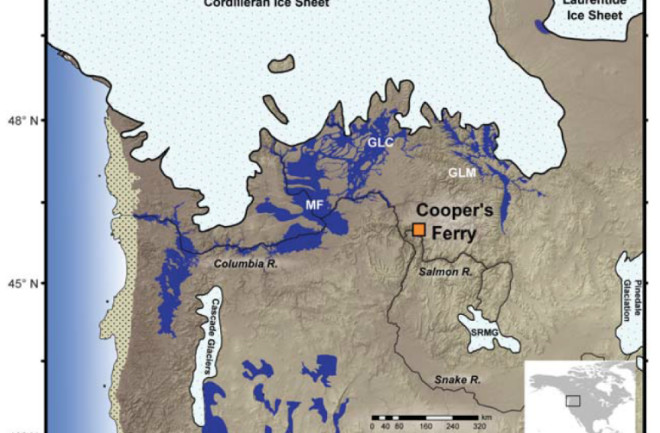

About 16,000 years ago, the Cooper’s Ferry site would have been south of the ice sheets blanketing much of North America, and far from smaller glaciers, including the Salmon River Mountain Glacier (SRMG). The site was also removed from the modeled path of the Missoula Floods (MF), multiple catastrophic events at the end of the last Ice Age, and the glacial lakes Missoula (GLM) and Columbia (GLC). Continental shelf along the Pacific that was exposed at the time is shown as a tan dotted area. (Credit: Davis et al 2019)

In the oldest layer at the dig, the team collected 189 stone artifacts, including projectile points and hand axes, as well as animal bones and a river mussel shell fragment. That layer is confidently dated to be 15,280-16,560 years old.

To Idaho…From Japan?

Stone tools, particularly projectile points, preserve a wealth of detail. Their shape reveals how they were made, how they were used and, occasionally, how they were repaired or resharpened. Archaeologists can use these often-subtle traits to determine whether artifacts from a wide geographic range belonged to a single style, suggesting they were made by people who shared the same culture.

Based on their analysis of the stone tools from Cooper’s Ferry, the researchers suggest that they are most similar to artifacts of the same general period found on the other side of the Pacific. Specifically, they appear to share many traits with tools produced on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido 13,000-16,000 years ago.

It’s a startling association, given the thousands of miles between the Japanese island and the banks of the Salmon River (more than 4,700, as the crow, or maybe the albatross, flies). Researchers will need to dig up a lot more evidence to make the case for any actual link between the sites — “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” and all that.

Consider, for example, the consequences of the Solutrean hypothesis. In the late 20th century, a couple researchers identified similarities in tool-making techniques between the Clovis tradition, the dominant early North American style, and the Solutrean tradition of southwestern Europe. They claimed these similarities indicated that Solutreans (with no known maritime tradition) had crossed the Atlantic and populated the Americas well before ancient Siberian populations arrived via Beringia. While it remains a fringe theory long on hype and remarkably short on solid evidence, the Solutrean hypothesis has been embraced by some white supremacists and still circulates in a number of faux-science YouTube clips. (For more, here’s a great primer on the Solutrean controversy, from a geneticist who participated in a much-maligned 2018 “documentary.”)

Back To Real Science…

While establishing a link to ancient Japanese tool-making traditions remains speculative, there’s no doubt the Cooper’s Ferry finds are significant thanks to their age. They’re yet more evidence that the First Americans arrived on the continent long before an ice-free overland route appeared.

The study appears today in Science.