There are multiple contenders for the title of “real” North Pole during the holidays, when its most famous inhabitant steps into the spotlight. Canada Post uses the postal code H0H 0H0 for letters to Santa Claus — you might even get one back — but the address is not assigned to any province or territory; this “North Pole” may be just a post office box. Meanwhile, North Pole, Alaska, a suburb of Fairbanks, features a year-round Christmas village and a giant statue of the jolly old elf, but its name is a misnomer. The small Alaskan city is actually situated 125 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

Even if you’re looking for the North Pole as a natural phenomenon, rather than as a cultural touchstone, you’ve still got your choice of candidates. Four distinct locations have legitimate claims to the title by various criteria.

The Geographic North Pole

This is “True North” — the geographic North Pole, the point at which all meridians of longitude (the lines on a map that run north to south) converge. It is one terminus of Earth’s axis, the imaginary spindle around which the planet rotates.

Even when they're marked on a globe, the real North and South Poles are not fixed points, because the Earth — being an ellipsoid rather than a perfect sphere — wobbles ever so slightly in its spin. This irregularity in polar rotation was confirmed in 1891 by American astronomer Seth Carlo Chandler. Various factors, particularly pressure changes on the sea floor, continually affect the Earth’s angular momentum. As a result of this “Chandler wobble,” the precise intersection of Earth’s surface with its axis wanders annually within a range of a few meters.

The geographic North Pole, unlike its southern counterpart, lies in the open sea — more precisely, on an ice-sheet riding the Arctic Ocean. Although it is officially designated international waters, a 2007 expedition engendered controversy by planting a Russian flag on the seabed beneath the pole.

The North Magnetic Pole

The location of the geographic poles must be deduced by the observable rotation of the Earth relative to the fixed stars. By contrast, the location of the North Magnetic Pole can be confirmed by direct observation. If you stood there — as you could, given that it is occasionally accessible by land, either in Greenland or Nunavut — the needle in your pocket compass would try to flip perpendicular and plunge toward the ground like a dowsing rod.

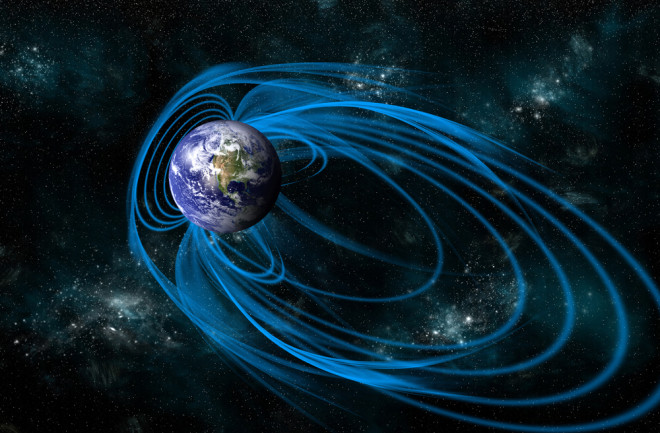

Earth’s magnetic field originates with its rotation. The planet's core is composed of iron and nickel — solid at the center, but liquid in the outer core. These inner and outer cores spin at different speeds; as in a power plant’s dynamo, this constant motion produces a self-sustaining electromagnetic field. The turning planet acts like a bar magnet, with its magnetic poles near the extremes of geographic north and south. Their precise position changes, subject to the currents of the liquid metals in the outer core. As a result, the North Magnetic Pole moves irregularly within approximately a 500-mile radius of the 90th parallel, or the geographic North Pole.

In a bar magnet, the two ends — or “poles” — have opposite polarities. You can visualize the whole thing as a tunnel; lines of magnetic flux exit from one end, arcing outward to double back and re-enter via the opposite end. The North Magnetic Pole is the entry point, where the lines of magnetic force arc down toward the Earth’s core. That's why the business end of a magnetized compass needle will try to plunge downward. In the study of magnetism, the pole of a magnet where the lines of flux enter is (confusingly) designated “south,” while the pole where they exit is considered “north.” This means that the geographically North Magnetic Pole is actually the south pole of the dipole magnet that is Planet Earth.

At least, it is for now — because the polarities of the poles can flip. The geological record shows that Earth’s magnetic field has reversed itself 183 times over the planet’s history, most recently about 780,000 years ago. Observation of similar reversals in the Sun’s magnetic field appears to indicate that these are spontaneous, random events. With Earth’s magnetic field observably weakening over the last few centuries, we may be due for another field reversal in the coming millennia.

The Geomagnetic North Pole

The magnetic field generated by the dynamo action of Earth’s core extends far into interplanetary space. This “magnetosphere” is shaped like an elongated teardrop, 10 Earth radii wide (64,000 km) at its sunward side and extending hundreds of Earth radii behind. This geomagnetic field deflects solar wind and cosmic rays, highly charged particles that in large doses would annihilate terrestrial life.

The field is not a perfect dipole. The solar wind distorts the magnetosphere as it extends into space, tilting it about 11 degrees relative to the rotation of the Earth. The geomagnetic poles refer to the points where the magnetosphere’s axis passes through the planet, and have been relatively stable over time. For many years, the Geomagnetic North Pole has lain on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, a sprawling territory in northern Canada.

During violent solar storms, charged particles slip through the magnetosphere into the upper atmosphere. When these particles collided with the gaseous particles in the Earth's atmosphere, it produces spectacular optical effects visible near the geomagnetic poles. In the northern hemisphere, we call this phenomenon the aurora borealis — more commonly known as the Northern Lights.

The Northern Pole of Inaccessibility

Of the four North Poles, the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility — precisely, 85 degrees, 48 minutes north latitude by 176 degrees, 9 minutes west longitude — is the odd man out, determined not by any property of physics but by geography. Interestingly enough, this aptly-named location actually is the middle of nowhere.

Poles of inaccessibility are manifestations of geographers’ preoccupation with extreme places: the highest, the lowest, the most remote. They are the points on the map at which, either on land or sea, you are furthest from a coast. Every continent, and every ocean, has its own pole of inaccessibility.

Accordingly, an unassuming bit of ocean gains distinction as the point in the Arctic that is farthest from land. It's roughly equidistant from Ellesmere Island, Henrietta Island in the East Siberian Sea, and Kosmomolets Island in the Russian Arctic, with nothing but frigid water and pack ice for at least 1,008 km in any direction.

An arbitrary distinction, perhaps. But if you’re still looking for the toymaker’s workshop, it might be your best bet. The old fellow does value his privacy, after all.