Some people go out of their way to help their peers, while others are more selfish. Some lend their trust easily, while others are more suspicious and distrustful. Some dive headlong into risky ventures; others shun risk like visiting in-laws. There's every reason to believe that these differences in behaviour have biological roots, and some studies have suggested that they are influenced by sex hormones, like testosterone and oestrogen.

It's an intriguing idea, not least because men and women have very different levels of these hormones. Could that explain differences in behaviour between the two sexes? Certainly, several studies have found links between people's levels of sex hormones and their behaviour in psychological experiments. But to Niklas Zethraeus and colleagues from the Stockholm School of Economics, this evidence merely showed that the two things were connected in some way - they weren't strong enough to show that sex hormones were directly influencing behaviour.

To get a clearer answer, Zethraeus set up a clinical trial. He recruited 200 women, between 50-65 years of age, and randomly split them into three groups - one took tablets of oestrogen, the second took testosterone tablets and the third took simply sugar pills.

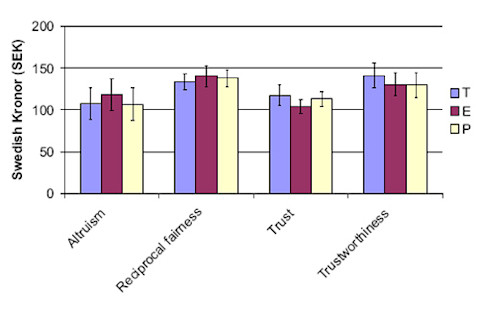

After four weeks of tablets, the women took part in a suite of psychological games, where they had the chance to play for real money. The games were designed to test their selflessness, trust, trustworthiness, fairness and attitudes to risk. If sex hormones truly change these behaviours, the three groups of women would have played the games differently. They didn't.

Their levels of hormones had changed appropriately. At the end of the four weeks, the group that dosed up on oestrogen had about 8 times more than they did at the start, but normal levels of testosterone. Likewise, the testosterone-takers had 4-6 time more testosterone and free testosterone (the "active" fraction that isn't attached to any proteins) but normal levels of oestrogen. The sugar-takers weren't any different. Despite these changes, the women didn't play the four psychological games any differently.

In a "Dictator game", they were given 200 Swedish Kronor and told to distribute it between themselves and a charity for the homeless - this was a measure of their selflessness. In an "Ultimatum game", a partner offered them a share of a 400 Kronor pot. If they accepted the offer, both players took their respective shares, but if they rejected it, neither player got anything. The cut-off point where they would accept the offers, even if they were small ones, indicated their attitudes towards fair play.

In a "Trust game", they had to give a share of a 150 Kronor pot to a "trustee". That investment was tripled and the trustee had to decide how much to give back to the "trustor". The women played both parts, with the trustor role measuring their level of trust in their peers, and the trustee role showing their own trustworthiness. Finally, the women had to choose between taking a 50/50 gamble on winning 400 Kronor and a certain but smaller payoff, from 80 to 300 Kronor. The point at which they took the chance determined their attitudes to risk.

Zethraeus found that the month-long regimen of hormones had absolutely no effect on the women's decisions during these games (see graph below; T = testosterone; E = oestrogen; P = placebo). And when he looked at their results individually, he found that the extent to which their hormone levels went up had no bearing on their choices either. Based on these stark results, he safely concluded that "sex hormones have no significant impact on economic behaviour".

That result may be surprising to some, especially in the light of earlier studies. According to some of these, testosterone-charged men are more likely to reject low, unfair offers in the Ultimatum game than those with lower levels, take bigger financial risks and make bigger profits. Women apparently take more risks during parts of their menstrual cycle when their oestrogen levels are highest.

But these results are mere correlations. This new trial is stronger, in that it actually manipulated hormone levels to see what would happen. It was randomised, which means that the decision about which tablet they received was made randomly. And it was "double-blind", which means that neither the volunteers nor the researchers knew which tablets they were taking. That was only revealed at the end of the trial when all the results were in. These features are incredibly important. They remove the temptation and the ability of the researchers to skew or bias their results, even unconsciously.

Based on his negative results, Zethraeus believes that the links observed in other studies may reflect a third factor - something else that affects behaviour and varies with levels of sex hormones. Rather more harshly, he suggests that the previous results could be "spurious". It's possible that negative results, which didn't find a link between behaviour and sex hormone levels, were simply never published, giving a rose-tinted and overly positive view of the evidence. This problem is called publication bias, and it means that some hypotheses wrongly appear to gain support, simply because negative results never see the light of day.

There are a few caveats to the current study. It only looked at women, although there's little reason to believe that sex hormones would influence risk-taking, selflessness or trust in men alone. It only examined the effects of a short four-week course of hormone treatments, although the boosted levels of hormones after the four weeks can't be ignored. Hormone treatments, which are commonly used to deal with menopausal symptoms and sexual disorders, produce changes of the size that Zethraeus saw. And finally, it only looked at changes in sex hormone levels later in life. Indeed, Zethraeus admits that his results don't rule out the possibility that testosterone or oestrogen levels during childhood or puberty could affect decision-making behaviour later on.

Nonetheless, the study provides a solid blow to the idea that sex hormones affect our attitudes to trust or fairness, and it reminds us yet again to be cautious about relying too heavily on correlations.

Reference: Zethraeus, N., Kocoska-Maras, L., Ellingsen, T., von Schoultz, B., Hirschberg, A., & Johannesson, M. (2009). A randomized trial of the effect of estrogen and testosterone on economic behavior Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0812757106

More on hormones (although interesting in the light of this study): Testosterone-fuelled traders make higher profits