Much of human history is hidden beneath the waves: Some 3,000,000 shipwrecks may rest on the world’s seabeds. But archaeologists had to rely on professional divers for scraps of information about these sites until the 1960s, when George Bass began to apply rigorous excavation techniques to underwater wrecks. Over the next half century, Bass led groundbreaking studies of Late Bronze Age (1600-1100 B.C.) shipwrecks off the coast of Turkey, along with sites from many other periods. Along the way, he transformed underwater archaeology from an amateur’s pastime to a modern scientific discipline. Those achievements earned him a National Medal of Science in 2002. Now a professor emeritus at Texas A & M University, where he founded the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, Bass reflected on his storied career with DISCOVER senior editor (and passionate lover of archaeology) Eric A. Powell.

Why go underwater to study the ancient past, when research is so much easier on land? Underwater artifacts are protected against the most destructive agent of all, which is us. People drop plates and break them. They drop glass bottles and break them. They burn marble columns for lime. They melt down bronze statues for church roofs. Also, there are certain things that are simply not going to be found on land, like raw materials, because they don’t remain raw for very long out of the water. The other reason to go underwater is that it’s the place to find evidence of ship hulls, which were as important to ancient cultures as architecture, pottery, anything. There’s always been a desire to transport goods or ideas as cheaply and in as great a quantity as possible. For much of human history, that meant building the best ship you could.

What can you learn from a ship hull? Since at least the Bronze Age, seafaring has been key to cultural progress. Ships are in some cases the most technologically advanced equipment a culture would develop—their space shuttles. So to really understand the ancients, you have to be able to understand how they approached the sea, and the only way to do that is to excavate shipwrecks. And those ships only sank once, so they can give you incredibly precise dates.

Have you always been drawn to ships and the sea?I grew up in Annapolis, Maryland, where my father taught English at the Naval Academy. My brother and I made a diving helmet out of a tin square that we cut out and put glass in as a faceplate. We would have died if we had ever tried it. I was also inspired by a retired Australian army officer named Ben Carlin, who made an amphibious jeep that went all around the world. He put it together two doors down from us. I used to help him after I came home from school—you know, tightening nuts. He thought he’d make his fortune from it. He wrote a couple of books about that jeep, but he never did make his fortune.

Were you also interested in archaeology from the beginning? Not at first. When I was in high school, I fell in love with astronomy. Later I went to Johns Hopkins and started as an English major. But then I spent my sophomore year of college in England at the University of Exeter, and I got what they call “rusticated” for pulling a prank. Forty of us got suspended because we raided a local agricultural college. I had nowhere to go. My brother’s roommate and some of his friends were going to Taormina, Sicily, for spring break and asked me to go with them. So here I was in Taormina, sitting out there in the evening and looking at a Roman theater with Mount Etna in the background, and I thought, you can make a living studying this stuff. Back at Johns Hopkins there was no archaeology department, but they made up a major for me with courses in the Near Eastern section and the classics section.

And then you had an amazing first experience as a field archaeologist. I went to the American School of Classical Studies in Athens and then excavated at the site of Gordion in Turkey, the capital of King Midas’s empire in the eighth century B.C. I found the first piece of gold, an earring, from the level of the site that dated to Midas’s time.

You had to leave archaeology temporarily in 1957 to serve in the Army. Did that slow down your archaeological career? Truth is, that was as important as any university degree I could have had. I was plunked down in a 30-man Army security unit in the middle of a rice paddy in Korea near the DMZ, the only American unit inside a Turkish brigade. It was a hardship outpost. The night I arrived the guys all got drunk and were rolling around in the rice paddies yelling obscenities at me. I was terrified; I didn’t know what to do. Well, I grew up that night, I guess. Suddenly I was in charge of generators, trucks, the food, the operation. When I got back to the States, Rodney Young, an archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania whom I’d worked with at Gordion, knew I’d had this formative experience. He had recently gotten a letter about a diver who’d found a Bronze Age shipwreck site off the coast of Cape Gelidonya in Turkey. Rodney asked If I’d like to go out and excavate this shipwreck.

Wait—did you even know how to dive at that point in your career? I had to learn. So I joined the Depth Chargers at the Central YMCA in Philadelphia. My teacher was an ex-Navy diver who had lost an eardrum in a diving accident. At the end of the sixth lesson, we were still practicing snorkeling. I said to him one night, “Could I try a tank on once? I leave for Turkey tomorrow and the site is a hundred feet deep.” And I found it very easy. I’ve never had any problems with diving.

So you started excavating at Cape Gelidonya in Turkey with only one diving lesson under your belt? That’s right—and it’s in the worst current in the Mediterranean. Cape Gelidonya was the first ancient wreck excavated in its entirety on the seabed, the first excavated by a diving archaeologist. Before, archaeologists would sit on the deck like dogs waiting for a bone and accept artifacts brought up by divers for them. The divers always were saying archaeologists could never learn to dive. But we could! Cape Gelidonya showed it.

Cape Gelidonya dated to 1200 B.C., making it the earliest known shipwreck at the time. What did those artifacts teach you about seafaring culture during that era? At the start we all assumed it was a Mycenaean, or Late Bronze Age, wreck. All the English, German, and French sources indicated that Mycenaeans, the people of the Homeric epics, had a monopoly on maritime commerce back then. The reason was that Mycenaean pottery had been found all over Egypt, the Palestinian coast, and Cyprus. So when we found copper and tin ingots, which are used to make bronze, we assumed they were being shipped to Greece to be made into bronze.

Then I started studying pan balance weights that we excavated from the site. I saw certain weights repeating themselves—multiples of 9.32 grams. That’s an Egyptian qedet. Or 7.20 grams, which was another standard unit in the Near East. And a lamp from the ship appeared to be Canaanite. I concluded that it was actually a Near Eastern ship, not Mycenaean after all. At that time all classical archaeologists thought that bronze had to come from Greece, that Greece was the center of civilization. But it’s really a cultural bias.

You were criticized for identifying it as a Near Eastern wreck. That excavation at Cape Gelidonya is the thing I’m proudest of in my career, and I didn’t get a single favorable review from archaeologists for my publication. But we later confirmed that the ship was from Cyprus, which was then part of the Near Eastern world. Underwater archaeologists were sneered at for so long. No one took us seriously. We were just a bunch of skin divers.

“Skin diver”—why that insult? Skin diving was a macho thing in those days. Archaeologists thought it was a bunch of jock divers out there. They didn’t understand you can work more carefully underwater than you can on land. You can excavate one grain of sand at a time. You can’t do that on land. I remember when an archaeologist, who shall remain nameless, called underwater archaeology “that silly stuff you people do, bringing up amphoras.” At that time we had the largest dated collection of seventh-century pottery in the world. He was publishing a book on late-Roman pottery going up to the seventh century a.d. and he was calling it silly stuff. I said, “What do you mean, ‘silly’?” He said, “Well, you can’t do careful work underwater.” And I said, “Yeah, you can. We map things very accurately.” He couldn’taccept the fact that a diver is not just some clumsy guy with lead shoes.

After Cape Gelidonya you went on to excavate other sites, including a seventh- century Byzantine shipwreck at Yassi Ada, an island off the western coast of Turkey. How did you find these sites?

Almost all the wrecks were shown to us by Turkish sponge divers. Based on the number of sponge boats, the number of divers, how long they go down, and how deep they go—all that stuff—we calculated once that if we interviewed every sponge diver about what they saw on the bottom, we’d learn as much as if one of us nautical archaeologists swam for a year. Some would say, yeah, but they are not doing scientific searches. Baloney. They were doing better searches than we ever did. Their livelihoods depended on it.

Despite your success, in 1969 you abandoned underwater archaeology. Why? At Yassi Ada, one of our most skilled, experienced divers, Eric Ryan, was very near death when we pulled him from the water with an embolism. And then we had a sponge diver also brought to us with the bends, or decompression sickness, which is caused by nitrogen bubbles forming in your blood if you come up too quickly. It was horrible. He was calling out to his wife and Allah. He died during treatment in our decompression chamber. Eventually I thought, I’ve had a decade now of doing this. The odds are that one day, maybe a coed will die and I’ll have to lift her dead body out of the water. Why don’t I just get out of it now while I’m ahead? I’ve tempted fate too often.

You switched to work on land at a site in southern Italy. Why there? It was a Neolithic [6000‒2800 b.c.] site. We were trying to determine when domestic animals were introduced into that part of Italy. We thought we might be able to study the bones and pottery to find that out. It didn’t work, and I remember thinking that out there somewhere in the Adriatic was probably a shipwreck that would answer this question so much better. Also, I just missed the smell of the sea and the seagulls and the rope and the smell of tar and all the things that surround boats.

So you hatched a plan to get back to your true love, underwater archaeology. In 1972 my colleague Fred van Doorninck at U.C. Davis came and stayed at our house in Philadelphia to work on this final publication about the Byzantine wreck at Yassi Ada. And we started talking about this little dream: What if we had an institute devoted to underwater archeology? We were naive. We thought we could get a compound out on a peninsula on the Turkish coast and grow our own vegetables and buy ourselves a trawler.

How did you finally take the plunge and turn that dream into something real? One day I got a call from a woman who said, “There’s this big piece of wood that’s washed up on the beach here in New Jersey.” She was wondering if it might be a Viking ship, and would I come down and look at it? My friend Dick Steffy, an electrician who built accurate ship models, and I went out and quickly saw it was modern, built in Maine around 1890. Then while we were driving home in separate cars I noticed Dick waving out of the window to stop. We pulled over to the side of the highway, he walked back toward me, and he said, “George, I’ve decided I’m going to make a career as an ancient shipwreck reconstructor.” I said, “Dick, there is no such thing. You’ve got a wife and children. You’ll starve to death.” He said, “If you don’t try something, you’ll just die and never know whether it would’ve worked.” I listened to him, and shortly thereafter I decided to leave Penn to found an underwater archaeology institute.

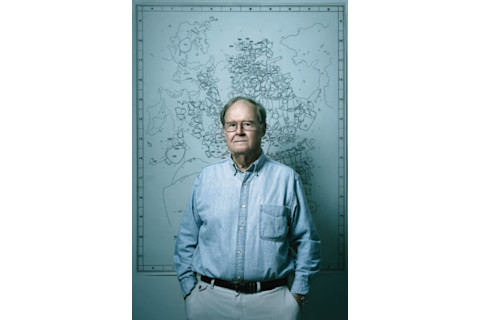

Photograph by Randal Ford

Eventually you found a home for the institute at Texas A & M and set up a series of intensive underwater surveys and excavations around the United States, the Caribbean, and off the coast of Turkey. Which site do you view as most important? No question, it is the Bronze Age wreck we excavated at Uluburun, Turkey, not far from Cape Gelidonya. A sponge diver reported seeing “strange metal biscuits with ears,” which were copper ingots, at the site. With my colleague Cemal Pulak taking the lead, we found the shipwreck, excavated it, and discovered it had 20 tons of raw materials, things that had never been seen before: intact tin ingots, almost 200 glass ingots, and ebony logs. We had half a ton of resin called terebinth, which was probably burned as incense. These are things you just never find on land. We had 10 tons of copper and 1 ton of tin, which is exactly the right proportion for 11 tons of bronze. Like the Cape Gelidonya wreck, the ship was clearly coming from the East, maybe the Palestinian coast, and carrying goods to Greece. It was an unprecedented window onto the Bronze Age economy.

How did that change our thinking about life in the Bronze Age? You name it—it contributed to so many fields: the study of weapons, the history of glass, the history of metallurgy, the history of ship construction, just endless.

Looking ahead, what kind of technology will nautical archaeologists need to keep the field advancing? The one I’m waiting for is a one-atmosphere flexible diving suit. That’s a diving suit that would be flexible but could still withstand enormous pressure. It would allow divers to go down and excavate for hours at a time without worrying about decompression. That would revolutionize the field. Right now we can only work twice a day for 20 minutes at a time because of complications due to the pressure at great depths.

What are the greatest discoveries left to be made in nautical archaeology? There’s a whole unknown early nautical history. Crete was suddenly colonized with domestic animals in 6000 B.C., so there must have been rafts or some kind of seafaring craft at that time. Same with Australia—but it was settled 40,000 years ago or more. There’s no reason why remains of the craft they used couldn’t survive, if they were protected by sand and sealed from decomposition. They just haven’t been found yet. It would also be interesting to know what kind of craft the Mesopotamians used. And I would love to do a survey of the Red Sea and find a pharaonic ship.

What about sites we already know about? Is there more to be discovered there? Of course. We recently re-excavated Cape Gelidonya with better equipment, better metal detectors, and found the site is larger than we thought. We found that pottery extended to the base of a rock that rises to just below the surface. The diver and photojournalist Peter Throckmorton, who first identified the site, thought maybe the ship had hit that rock. Then 50 years later we found a trail of artifacts from that rock to the rest of the site, confirming his hunch.

That’s an incredible leap through time, to a specific moment 3,200 years ago. When you’re at a site, do you imagine what it was like to be aboard the sinking ship? Back when I was running excavations, I was more worried about keeping my crew alive. But after I retired I was looking through some family history compiled by my grandfather. I found a note: “William Jessup Armstrong, grandfather, lost in the sinking of the Atlantic.” I’d never heard of that, so I went down to the library and learned that the Atlantic sailed from Connecticut just before Thanksgiving in 1846 with some 80 people aboard. Then something blew up on the ship, and it was drifting in a terrible storm not far from shore. Forty people died, and on the list, there’s his name: “Lost—the Reverend Doctor Armstrong.” So I visited where the Atlantic went down and discovered that people have collected spoons and things from the site. That led me to think about all the stuff I’ve collected from shipwrecks over the years.

How did that change the way that you conceptualize the past? When I excavated a classical Greek shipwreck at a site called Tektas Burnu, my students asked me, “Do you think anyone made it ashore?” And I said, “Of course, it sank just a few feet from shore.” But you know what? The shore’s got jagged rocks, and with a storm, they would’ve had waves crashing over them. I hadn’t thought about it until this. The Atlantic went aground on a beach, and yet still half the passengers died. It just brought it home: Every one of these shipwrecks we excavate is possibly a site of terrible human tragedy.

10 Undersea Tales

by Mary Beth Griggs

1.

Bronze Age Merchant Ship Cape Gelidonya, Turkey

Archaeologists long assumed the Greeks ran the economic show in the Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age. Then, in the summer of 1960, George Bass excavated a ship dating to 1200 B.C. off the southern coast of Turkey. The vessel—the first completely excavated underwater—was carrying Near Eastern plaques, copper ingots, and other goods from the East to Greece, not vice versa. The site upended conventional wisdom about Bronze Age trade and marked the beginning of scientific underwater archaeology.

2. 17th-century Swedish Warship Stockholm Harbor In 1628 the ornate Swedish warship Vasa sank less than a mile into its maiden voyage. In 1961 archaeologists raised the ship from the seabed, making it the first major shipwreck to be recovered almost intact, and giving researchers a unique look at 17th-century naval warfare. In the early 2000s large deposits of sulfuric salts were found eating away at Vasa’s hull, prompting researchers to develop new conservation methods that could help save Vasa and other excavated ships.

3.Viking Ships Roskilde, Denmark Most shipwrecks are the victims of unforeseen catastrophe, but five Viking-era ships excavated in 1962 near the Danish town of Roskilde, outside Copenhagen, were sunk on purpose. The ships formed part of an underwater rock barrier that was constructed in the 11th century to protect Roskilde from sea raids. Centuries underwater had made matchsticks of the ships’ hulls, but researchers managed to piece them together from more than 100,000 splintered bits of wood. The vessels gave archaeologists an unprecedented look at Viking shipbuilding techniques.

4. Kamikaze Fleet Takashima Island, Japan Legend has it that when Kublai Khan, the Mongol emperor of China, invaded Japan in 1281, his fleet was destroyed by a typhoon the Japanese dubbed a kamikaze, or “divine wind.” Celebrated in art (such as the 19th-century engraving below), the tale persisted, unproven, until the 1980s, when archaeologists diving off the small island of Takashima found copper coins, metal helmets, and arrowheads dating to the 13th century. Last year’s discovery of the substantial remains of a ship confirmed that the khan’s fleet has indeed been found.

5. Union warship Outer Banks, North Carolina On December 31, 1862, the USS Monitor sank in rough waters off the coast of North Carolina, carrying 16 Union sailors to their deaths. The wreckage of the ironclad warship was discovered by sonar in 1973. Over the next 20 years, archaeologists removed 210 tons of relics from the seafloor, including the ship’s iconic gun turret (seen in an 1862 photograph above) and more intimate objects like buttons and silverware used by the sailors on board. While conserving the ship’s remains, researchers were able to study the inside of Monitor’s 20-ton, 400-horsepower engine, one of the most advanced of its time.

6. Sunken Caribbean Port Port Royal, Jamaica Shipwrecks are not the only important archaeological sites preserved underwater. Nestled along the southern Jamaican coast are the remains of Port Royal, a colonial city (and pirate haven) that partially sank into the sea after a devastating earthquake in 1692; some of the town’s neighborhoods dropped 15 feet in an instant. Excavated from 1981 to 1990, Port Royal offers a glimpse into both the panicked moments after the earthquake and the everyday lives of Port Royal’s 17th-century residents, commoners who rarely show up in historical documents. Archaeologists have made discoveries both poignant—a pocket watch from the site forever set to 11:40 a.m., around the time of day the earthquake hit—and prosaic, such as hair clippings, perhaps from a pirate’s recent haircut, and intact glass liquor bottles.

7.American Zeppelin Big Sur, California Imagine the Titanic floating overhead: That’s what it would have been like to see the USS Macon fly by. Nearly 800 feet long, the airship was completed in 1933 as part of an effort to equip the U.S. Navy with airborne military bases. With an onboard hangar, Macon was capable of launching five small fixed-wing planes in midair, but it never saw action and went down off California’s Big Sur coast during a storm in 1935. Rediscovered in 1980 when a fisherman caught a piece of the airship’s debris in his net, the wreck was recently surveyed and mapped using sonar and remotely operated robots. Government archaeologists continue to explore the unique site, which lies in 1,500 feet of water.

8.A Pirate’s Flagship North Carolina Coast In the early 18th century, Blackbeard was the most feared of the pirates who preyed on vessels traveling to and from the American colonies. His specter returned in 1996, when archaeologists searching off the North Carolina coast discovered Blackbeard’s flagship, the Queen Anne’s Revenge, which ran aground in 1718 as the pirates fled English warships. A team has excavated at the site ever since, recovering cannons, a copper disk depicting Queen Anne herself, and personal effects such as pipes. What the crew left behind and what they took as they evacuated tell researchers what pirates of that period valued most—information that ships’ logs did not record.

9.Phoenician Trader Bajo de la Campana, Spain Along Spain’s southeastern coast, a treacherous rock formation called Bajo de la Campana has claimed many ships through the years. They included a 7th-century B.C. Phoenician trading vessel of a type depicted in contemporary wall reliefs. The recent excavation of the ship opened a window onto the maritime economy of the Phoenicians, a Near Eastern people who built a trading empire throughout the Mediterranean from 1500 to 600 B.C. As it sank, the ship left a trail of artifacts on the seafloor, including tin ingots, elephant tusks, and vials of perfumed oils, illustrating just how active the Phoenician trading system was. The vessel was most likely bound for a Phoenician colony just north of the wreck site.

10. HMS Investigator Banks Island, Canada

The British navy sent Investigator to the Arctic in 1850 to search for a doomed expedition led by explorer John Franklin. But Investigator was also unlucky. Its crew abandoned the ship after it was trapped in ice 500 miles north of the Arctic Circle. In 2010 archaeologists used sonar to find the ship sitting upright in 36 feet of water. Dives at the wreck gave researchers a new look at how the British outfitted vessels for polar navigation. Modifications made to strengthen the bow and hull against ice allowed the wreck to survive virtually unscathed for 160 years.