Spatial linguistic variationSpatial genetic variationTemporal linguistic variationTemporal genetic variation

PaleolithicVery highHighModerate-to-highModerate-to-low

NeolithicModerateModerate-to-lowModerateHigh

Bronze AgeModerate-to-lowLowModerateModerate-to-high

Iron AgeLowLowModerate-to-lowModerate

Modern AgeVery lowLowLowModerate-to-low

In the comments below I posited a scenario to explain a strange inference from a paper from a few years back, Sequencing of 50 Human Exomes Reveals Adaptation to High Altitude:

Population historical models were estimated (8) from the two-dimensional frequency spectrum of synonymous sites in the two populations.

The best-fitting model suggested that the Tibetan and Han populations diverged 2750 years ago

, with the Han population growing from a small initial size and the Tibetan population contracting from a large initial size (fig. S2). Migration was inferred from the Tibetan to the Han sample, with recent admixture in the opposite direction.

2,750 years would place the divergence of modern Tibetans and Chinese a few hundred years before Confucius. In fact, it would technically post-date the first historically attested Chinese writing, from the Shang dynasty. This result was pretty incredible, though one of the main authors believes it is a reasonable estimate. There are many ways you can explain this sort of divergence time, but one way which I elucidated below is rather simple. Imagine, if you will, a large set of populations which are culturally very distinct, but engage in gene flow with each other. This is not a preposterous scenario. Because of the restrictions on the manner in which genes are inherited, and the flexibility of cultural traits in terms of transmission, you often have situations where change in allele frequency is clinal while change in culturae is punctuated. To give a concrete example, moving along a transect on the North European plain will result in a gradual change in allele frequencies, but a crisper shift in languages spoke. The two are not totally distinct. Allele frequencies will tend to shift more at language boundaries, but whereas most of the difference is between groups across languages, in relation to genes usually the differences are within groups. But this is today. How about in a pre-modern context? We know that during the Shang dynasty, from which we have some written records, that the North China plain was multi-ethnic. In fact, the successor dynasty of the Shang, the Zhou, were themselves in part derived from the non-Han populations to the west of the Shang heartland ("Rong & Di"). By the time of the First Emperor, less than 1,000 years later, all of my reading indicates that that the North China plain had become overwhelmingly Sinicized (there seem to have been exceptions, but by and large the barbarian fringe had been pushed north, south, and west).

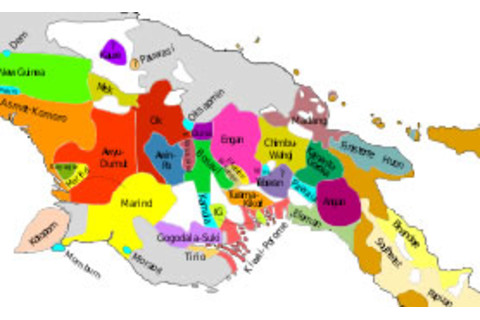

That's culture. How about genes? It may be that the peoples of what became North China were genetically very similar, but culturally very distinct. This is not a far-fetched scenario. Consider New Guinea, which is home to numerous language families, but where the Papuans are clearly a distinct population genetic cluster (race?), with affinities to island Melanesians, and more distantly to Australian Aborigines. What I am suggesting is that in the distant past it may not have been exceptional to have scenarios of cultural fragmentation coexist with moderate levels of gene flow. The gene flow would homogenize allele frequencies, while the functional details of culture could still maintain separation and distinctiveness. This then could explain the Tibetan cultural distinctiveness, especially in language, from the Han, despite genetic commonalities. Both these populations may derive from one of a set of nearly genetically interchangeable tribes, but the languages that these tributes spoke may have derived from far more deeply diverged lineages (in this specific case, you may have had extensive genetic admixture of several Paleolithic tribes as they nearly simultaneous transitioned to farming). Allelic distinctiveness can "blend away" on the genetic level while cultural distinctiveness can remain vibrant. But what about on a broader points? The table above is a schematic I generated trying to collect my own thoughts. The assertions are less what I think was true, than what I think may be true. I arrived at them mostly by imagining phylogenetic trees, biological (genes proper) and cultural. In a hunter-gatherer environment I envisage that the cultural landscape is extremely fragmented. Though language families may spread (e.g., Pama-Nuyngan) and homogenize the Paleolithic world, without a literate class and powerful states fission and evolution would rapidly kick in, and the tree would diversify outward. As we come closer and closer to the present I perceive that there are more powerful brakes on evolution and diversification, from ritual elites maintaining sacred languages, all the way to widespread literacy and a common canon. Additionally, after initial expansions and diversification, such as with Romance languages, there has been subsequent homogenization. The diversity vulgar Latin dialects which stabilized into the Langues d'oïl have slowly be swallowed up by standard French over the past few centuries (and to be clear, French has been eroding the dialects of southern France as well). The only situation where I suspect that I may confuse some readers is the last column: temporal genetic variation. The largest proportional change in allele frequencies and concomitant reduction in diversity probably occurred during the Neolithic. Though Peter Bellwood's thesis in First Farmers is overly stylized, I still believe that one can not understand the shape of cultural and genetic variation today without understanding the transition to farming. What happened during this period? Hunter-gatherers may have engaged in vicious inter-group conflict, but winner-take-all dynamics and positive feedback loops became much more common with the Neolithic. A small group, such as the tribes of Roma, could now become lords of much the world. Initial successes led to further successes. In contrast, the victories of the Paleolithic were probably less scalable. These demographic shifts kept occurring down to the Iron Age, for example, both the Bantu and Polynesian expansions. In fragments I have outlined all this before. The only issue where I think that added emphasis needs to be placed is that I believe one must keep in mind possible important discordances between the trees of cultures and genes. These discordances may date back to the early Neolithic. The Tibetans and the Han Chinese may be one obvious case. Though I think this is too simplified, Indo-European and Dravidian languages and cultures may be another. I suspect that the Dravidian languages derive from the Neolithic populations of western Iran. Indo-European may be a later daughter of a language families with roots from the Caucasus to the Volga. Genetically the original speakers of Indo-European and Dravidian may have had great similarities simply due to gene flow.* But, the two language families are very different, a reflection of a time when linguistic diversity was far greater than is the norm today over the same "genetic space." Ultimately, I'm basically saying that the reconstruction of the genetics and cultures of the past is rather like three dimensional chess. Not impossible, but certainly not easy. Genetics is probably going to be more tractable than culture, though one can not understand how the former came to be without some consideration of the latter. * The ANI component of South Asians is very close to other West Eurasians

Image credit:Wikipedia