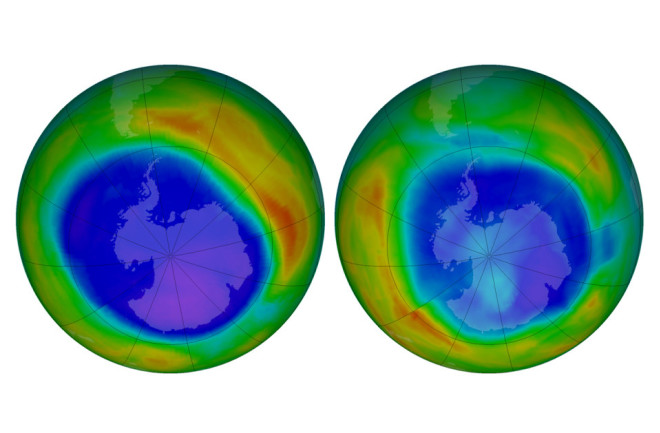

The Antarctic ozone layer is after decades of destruction due to anthropogenic emissions. It's a rare win for the environment, and this year, the ozone hole was the smallest it's been since its discovery in 1980.

But a new study shows that it might take longer for the ozone layer to fully recover than originally predicted. Scientists found last year that a new source of chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, was seeping into the air. CFCs react with ultraviolet light in the stratosphere and eat away at the ozone layer.

So, for a report in Nature Communications, researchers from the University of Leeds made computer models to show the effect of the new CFC emissions on the ozone's recovery. Weakened spots in the ozone layer mean higher radiation beaming down onto the planet, causing damage to animals, people and vegetation in the Antarctic.

Originally, it was predicted that the hole would close up by 2060. With more CFCs being released into the atmosphere, however, researchers say the recovery process could be delayed by up to 18 years, putting new predictions at around 2078.

Who's Making CFCs?

We've known for years that CFCs are dangerous to the ozone layer — so dangerous that world leaders agreed under the Montreal Protocol to phase out production of items containing the compound.

But a 2018 study using data from atmospheric monitoring stations in South Korea and Japan found that a new source of CFCs, specifically CFC-11, was coming from somewhere in eastern China. Since CFC-11 is commonly used in the production of foam insulation for buildings and refrigeration, researchers theorize that someone may have resumed production of such items containing the chemical.

“That was the first sign that the Montreal Protocol had been sort of violated," says Martyn Chipperfield, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Leeds. "Up until then, we had sort of thought people were going along with it, and [that] things would go along as expected.”

And it's not just the production of insulation that releases CFCs into the atmosphere — when a building or appliance is destroyed, it releases more of the toxic particles into the air. So the estimates from current CFC levels might not account for future emissions.

"There’s a large uncertainty in the amount of CFC level that’s being produced," Chipperfield says. "Even though the observation stages have detected emissions to the atmosphere, that’s unlikely to be all the CFC-11 that’s been made."

Not a Lost Cause

If CFC production is halted within the decade, researchers predict the ozone layer's recovery might only be delayed by a few years. But if production continues, the recovery could take decades longer.

“It will still recover and get smaller, but at a much slower rate,” Chipperfield says. Slowed-down recovery means the weak Antarctic ozone layer could let in radiation for a longer time, causing damage to life on the continent and in the surrounding oceans. But the nearly two-decade delay is a worst-case scenario, and Chipperfield is optimistic that the mysterious CFC emissions won't continue forever.

“The likelihood of no action being taken and the people doing this just carrying on is probably small, given the attention that’s been brought on it,” he says.

As notes from the Montreal Protocol meeting in May reveal, the Chinese government is reportedly in the process of establishing a system to better track CFC emissions and penalize companies that produce them. Only time will tell how much emissions will slow — or, if the ozone is lucky, stop altogether.