The first letter in the English alphabet is famously thought to be descended from a 4,000-year-old ox’s head. Over millennia, minor stylistic shifts slowly reshaped an ornate Egyptian hieroglyph into the austere “A” we see today. For centuries scholars have suggested that all letters follow the same trajectory: They start out as iconic representations of real objects, then gradually morph into simpler abstract shapes. But the forces that guide these transformations still remain poorly understood.

To fully decipher the process, you’d need an unbroken record of those incremental changes — in other words, every variation between the ox and the A. Since only fragments survive from the earliest phases of writing (which was invented independently four times, in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and Central America), it’s likely impossible to trace the complete history of most writing systems.

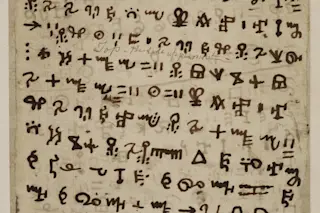

The unusual origins of one West African script, however, may offer a unique window into the mechanisms that molded its ancient predecessors. The Vai language of Liberia had no written form until 1833, when an industrious group of eight men invented one from scratch, writing with ink made of crushed berries. Its progression since then is well-documented, allowing researchers to observe what may have happened in the moments after the “Big Bang” of other scripts.

Piers Kelly, a linguistic anthropologist at Australia’s University of New England, and his colleagues compared Vai manuscripts from every few decades, using computational analysis to track the development of its 200 syllabic letters across two centuries, according to a study published in Current Anthropology in December. Based on the results, they concluded that writing systems evolve toward simplicity. “Left to their own devices,” Kelly says, “letters go from being more complex to less complex.”

Evolution by Laziness

The experiment confirmed the researchers’ hypothesis: When we write, we follow the “least effort principle,” an idea that researchers have also used to explain how spoken language changes in subtle ways to reduce the work required of its speakers. Applied to written language, this suggests that we will invest as little mental and physical energy as possible in every letter, the logical result being a script whittled down to the essentials. So long as each letter remains distinguishable from the rest, our laziness will steer us toward ever greater simplicity.

As early as the 18th century, intellectuals caught glimpses of this concept. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau noticed that writing had progressed from pictures to words, and then to alphabets. Future generations refined his observation. A century later, the German philologist Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl (Friedrich Nietzche’s favorite teacher, coincidentally) wrote that scripts change according to “certain laws or guiding impulses.”

Now Kelly and his team believe they’ve pinned down one of those laws, expressed nicely in a common paraphrase of Einstein: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Though it’s perhaps unfair to say that letters merely become “simpler.” Kelly prefers the term “compressed,” because it emphasizes the fact that each one still conveys the same amount of information, only with less “descriptive effort” — they’re not less sophisticated, just easier to produce. Aptly, one measure the study used to judge complexity was how much mathematical work it takes to compress the symbol into a digital file.

The Bare Minimum

The human urge to pare down symbols for efficiency’s sake has already been demonstrated. In a type of experiment called a transmission chain (where researchers ask one person to draw an image, then ask a second to imitate the first, and so on in a graphic game of telephone), intricate images rapidly become cruder until they achieve optimal simplicity.

In one memorable study — a game of Pictionary with a twist — participants drew the same subjects over and over for a partner to identify. The first round demands tremendous detail to establish the connection in the partner’s mind. Then, increasingly abstract symbols can recall the same meaning. One of the images was Clint Eastwood. The initial version depicts him in full Western garb, pistol on the hip. But by the last round he’s represented by just the faint outline of a cowboy hat.

This is what many linguists believe happens in the initial phase of a writing system. Complex symbols are helpful for the first generations who learn them, because they leverage mental shortcuts. For this reason, it makes sense to use an image of a pregnant woman to denote the syllable for “mother,” as the early versions of Vai did. But iconic pictures are onerous to draw, and over time unnecessary details fall away, leaving only what is truly needed to get the point across. It’s almost like the writers are testing the minimum they can get away with. “Once we’ve pinned it down to a meaning and a sound,” Kelly says, “what’s the path of least resistance?”

Seeking Equilibrium

The claim that letters become simpler over time must confront the reality that most scripts today seem remarkably stable. Many haven’t changed significantly in centuries. Everyone who can read English, or any other language that uses the Latin alphabet, can just as easily read the words inscribed on a 2,000-year-old Roman monument. Kelly argues this is because the ABCs have long since found their happy medium. “Just eyeball them,” he says. “They’re all pretty much the same number of strokes.”

So compression — the process by which letters become visually simpler but retain the same meaning — can’t go on forever. Rather than evolve into indistinguishable shorthand, each writing system will sooner or later reach equilibrium at its ideal level of complexity: a balance that makes it easy to memorize and write letters, yet also easy to tell them apart. Small changes may still occur, but at a much slower rate.

The Vai study provides another lesson to that effect. It found that the more complex a letter began, the more it eventually simplified. “The supercomplex signs drop dramatically,” Kelly says, “whereas the simpler signs barely budge at all.” In Vai, the poster child for this phenomenon is a letter pronounced like “ga,” which started with two outrageously long, wavy lines. By 1900 the lines had been cut to size, somewhat like W’s, and they haven't changed a bit since. Following the law of compression, writers adjusted this unwieldy letter to fit within the same range of complexity as the rest of the script.

Pressures Beyond Compression

Counterexamples abound, and critics often point to them. Hieroglyphics, for example, endured more than three millennia without dumbing down their complexity. But Kelly insists this doesn’t undermine his theory — it just shows that compression isn’t the only process at work. He notes that Egypt employed the script for religious purposes, which likely counteracted the bias toward simplicity. (Nowhere is lettering more worshipfully decorative than in a medieval monk’s handmade Bible, for example.) Alongside hieroglyphics, administrators and businessmen used the plain hieratic and demotic scripts to keep their secular world spinning.

Then there’s Chinese. In a paper yet to be published, Kelly and his colleagues found that the system’s beautifully convoluted characters have actually grown more complex in its 3,000-year career. But again, there’s an explanation: Script expansion. As more characters were introduced over the years, it took more complexity to differentiate them. English, with only 26 letters, obviously doesn’t face this dilemma.

In other words, diverse forces compete with compression to direct the evolution of letters, and the outcomes clearly vary depending on each script’s circumstances. In the modern era, all sorts of other historical and technological factors might contribute, especially the advent of the printing press and rising global literacy rates. “We’re in a completely new phase,” Kelly says. And while his paper focuses on individual letters as solitary units, Heriot-Watt University psychologist Monica Tamariz writes in a response to the study that their fates are intertwined — tweak one, and the rest may suddenly be subject to new pressures.

Even if compression can’t be detected in every case, Kelly says, that’s no cause to dismiss it as a universal rule. Given that humans of every age share the same brains and motor abilities, it stands to reason that Egyptians and people in the 21st-century have subconsciously shaped their scripts in the same way as the Vai writers. “I think we can be fairly confident,” he says, “that what was true of Homo sapiens in West Africa in the 1830s was true of Homo sapiens in Mesopotamia in 3100 B.C., and is true of us today.”