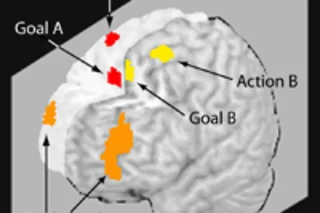

In the digital age, many of us are compulsive multi-taskers. As I type this, I’m listening to some gentle music and my laptop has several programs open including Adobe Reader, Word, Firefox and Tweetdeck. I’ve always wondered what goes on in my brain as I flit between these multiple tasks, and I now have some answers thanks to a new study by Parisian scientists Sylvain Charron and Etienne Koechlin. They have found that the part of our brain that controls out motivation to pursue our goals can divide its attention between two tasks. The left half devotes itself to one task and the right half to the other. This division of labour allows us to multi-task, but it also puts an upper limit on our abilities. Koechlin has previously suggested that the frontopolar cortex, an area at the very front of our brains, drives our ability to do more than ...

When multi-tasking, each half of the brain focuses on different goals

Discover findings from a multi-tasking brain study revealing limits of the human brain in handling multiple tasks effectively.

ByEd Yong

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe