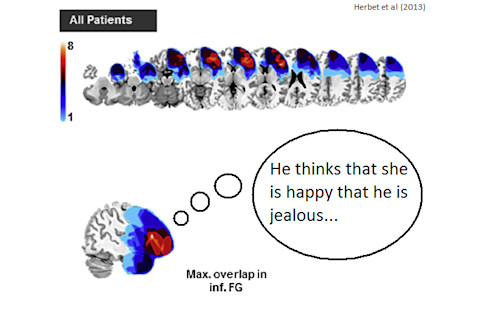

Neuroscientists are interested in how brains interact socially. One of the main topics of study is 'mentalizing' aka 'theory of mind', the ability to accurately attribute mental states - such as beliefs and emotions - to other people. It is widely believed that the brain has specific areas for this - i.e. social "modules" (although today most neuroscientists are shy about using that word, it's basically what's at issue.) But two new papers out this week suggest that people can still mentalize successfully after damage to "key parts of the theory of mind network". Herbet et al, writing in Cortex, showed few effects of surgical removal of the right frontal lobe in 10 brain tumour patients. On two different mentalizing tasks, they showed that removal caused either no decline in performance, or only a transient one.

Meanwhile Michel et al report that the left temporal pole is dispensable for mentalizing as well, in a single case

report in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience

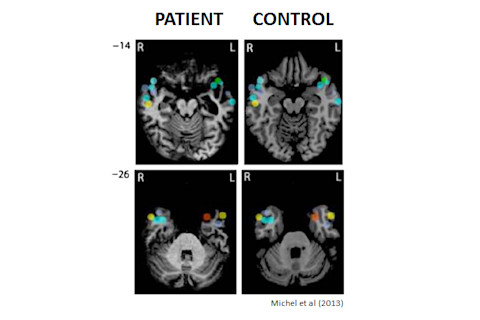

. They describe a patient suffering from frontotemporal dementia (FTD), whose left temporal lobe was severely atrophied. He'd lost the use of language, but he did quite normally on theory of mind tests adapted to be non-linguistic. In both papers, these patients don't have those parts of the brain that are most activated in fMRI studies of mentalizing. Where the blobs on the brain normally go, they have no brain. Here's an example from Michel et al showing the average peak activation spots seen in mentalizing tasks, projected onto the brain of the FTD patient and a control:

As you can see, however, the right side of the brain was in much better shape. So I think that's a major caveat here. All of these patients lost large parts of one half of the brain, but none (as far as I can tell) lacked the corresponding areas from both sides. So it could be that the inferior frontal cortex and the temporal pole are indeed key to theory of mind, but you can get away with only one of each. The fact that we have a pair of each, one left one right, provides redundancy. A bit like kidneys. This is quite plausible, but it's still interesting that the brain seems to be able to almost seamlessly cope with the loss of one of the halves. And it does make you question what it means when activity in one of these areas is found to be reduced in (say) people with autism - on one side of the brain only. If activity can be zero on one side, without any problems, does it matter if it's down a little?

Herbet G, Lafargue G, Bonnetblanc F, Moritz-Gasser S, & Duffau H (2013). Is the right frontal cortex really crucial in the mentalizing network? A longitudinal study in patients with a slow-growing lesion. Cortex PMID: 24050219

Michel C, Dricot L, Lhommel R, Grandin C, Ivanoiu A, Pillon A, & Samson D (2013). Extensive Left Temporal Pole Damage Does Not Impact on Theory of Mind Abilities. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience PMID: 24047381