Kentucky, USA. A woman known only as SM is walking through Waverly Hills Sanatorium, reputedly one of the “most haunted” places in the world. Now a tourist attraction, the building transforms into a haunted house every Halloween, complete with elaborate decorations, spooky noises and actors dressed in monstrous costumes. The experience is silly but still unnerving and the ‘monsters’ often manage to score frights from the visitors by leaping out of hidden corners.

But not SM. While others show trepidation before walking down empty corridors, she leads the way and beckons her companions to follow. When monsters leap out, she never screams in fright; instead, she laughs, approaches and talks to them. She even scares one of the monsters by poking it in the head.

SM is a woman without fear. She doesn’t feel it. She has been held at knifepoint without a tinge of panic. She’ll happily handle live snakes and spiders, even though she claims not to like them. She can sit through reels of upsetting footage without a single start. And all because a pair of almond-shaped structures in her brain – amygdalae – have been destroyed.

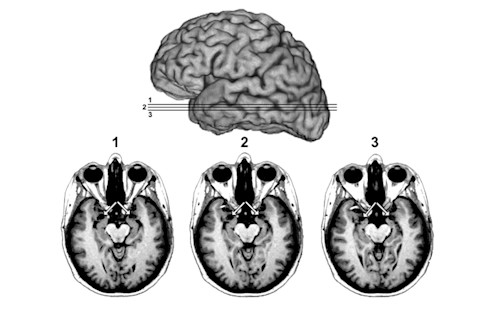

Ralph Adolphs, Antonio Damasio and Daniel Tranel at the University of Iowa have been working with SM for over a decade. She is a 44-year old mother-of-three, who suffers from a rare genetic condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease, which has caused parts of her brain to harden and waste away. This creeping damage has completely destroyed her amygdala, a part of the brain involved in processing emotion (white arrows in the diagram below). She’s one of the few people who shows such a striking pattern of damage.

Even so, her IQ is normal. Her memory is good, as are her language and perception skills. But she has problems dealing with fear. Way back in 1994, the group showed that SM has trouble recognising fear in other people. She can’t tell what fearful facial expressions mean, even though she’s more than capable of discerning other emotions. Even though she’s a talented artist, she can’t draw a scared face, once claiming that she didn’t know what such a face would look like. Now, in a study led by Justin Feinstein, the team have found that SM cannot feel fear either.

During her visit to Waverley Hills, SM rated her level of fear throughout the experience. She said that she was excited and enthusiastic in the same way that she feels when she rides a rollercoaster, but never scared – her scores always stayed at zero. In a similar trip to an exotic pet store, her levels of fear never climbed over a score of 2 out of 10. Even though she claimed to “hate” snakes and spiders, she was drawn to the snake enclosure, was excited about holding a serpent (“This is so cool!”) and had to be told not to touch or poke the bigger, more dangerous snakes (and a nearby tarantula). Why? She was overcome with “curiosity”.

When Feinstein showed SM a set of film clips, she generally behaved on cue, laughing at the happy clips and shouting in revulsion at the disgusting ones. But in response to ten scary film clips (including The Shining, Seven, and The Ring)… nothing. She showed no signs of terror, nor did she report any. She said that most people would probably be scared by the films but she herself felt nothing.

SM’s unusual reactions during these isolated scenarios are reflected in her day-to-day life. When Feinstein gave her an electronic handheld “emotion diary”, she reported feeling every basic emotion other than fear. In fact, out of a range of 50 possible emotional descriptions, the one she rated most highly over 3 months was “fearless”. (It’s fascinating data, although (and Feinstein admits this) it’s unfortunate that he didn’t collect similar data from healthy individuals to compare against).

After more digging, Feinstein uncovered a history of behaviour consistent with a lack of fear. SM’s eldest son can’t remember a single instance when mom felt fear or looked like she was scared. His anecdotes even support the results of Feinstein’s pet store trip. “Me and my brothers… see this snake on the road,” he writes. “I was like, ‘Holy cow, that’s a big snake!’ Well mom just ran over there and picked it up and brought it out of the street, put it in the grass and let it go on its way… She would always tell me how she was scared of snakes and stuff like that, but then all of a sudden she’s fearless of them. I thought that was kind of weird.”

Other events in SM’s life are less benign. Fourteen years ago, she was walking through a small park at 10pm, when a man beckoned her over to a bench. As she approached, he pulled her down stuck a knife to her throat and said, “I’m going to cut you, bitch!” SM didn’t panic; she didn’t feel afraid. Hearing a church choir sing in the distance, she confidently said, “If you’re going to kill me, you’re gonna have to go through my God’s angels first.” The man let her go and she walked (not ran) away. The next day, she returned to the same park.

These sorts of things happen to her a lot. It’s not that SM has had a cosseted life. She lives in a poor area “replete with crime, drugs and danger”. As Feinstein writes, “she has been held up at knife point and at gun point, she was once physically accosted by a woman twice her size, she was nearly killed in an act of domestic violence, and on more than one occasion she has been explicitly threatened with death.” But in most of these situations, she didn’t act with urgency or desperation, something that police reports have corroborated.

It’s not that she doesn’t understand the concept of fear; after all, she knew that other people might be scared by the films she saw. However, she has a lot of problems with detecting danger. In a previous study, the team showed that she has no personal bubble. She’ll happily stand a foot away from complete strangers, far closer than most people would be comfortable with (even though, again, she understands the concept of personal space). It’s no surprise that she gets herself into a lot of difficult situations.

It’s fascinating how this looks to other people. A few years back, the team asked two clinical psychologists to interview SM without any knowledge of her condition. They described her as a “survivor”, as “resilient” and even “heroic” in how she coped with adversity. If you ask the woman herself, she’ll say that she feels upset or angry in the face of danger, but never fearful. Feinstein even thinks that because of her brain damage, she could be immune to posttraumatic stress disorder, a trait that she shares with some combat veterans.

It wasn’t always like this. She remembers being afraid of the dark as a young child, running away screaming when her older brother jumped out from behind a tree, and being pinned to a corner by a large Doberman (“That’s the only time I really felt scared. Like gut-wrenching scared”). But all of these events happened before her disease wrecked her amygdalae. During her adult life, Feinstein couldn’t find a single episode where she clearly experienced fear.

But Elizabeth Phelps, who studies emotion at New York University, isn’t convinced. Her team has also worked with people whose amygdalae have been severely damaged and while they also have trouble recognising fear in others, they all feel fear in their normal lives (as assessed with similar diaries to the ones that Feinstein used).

Given the fact that SM is just a single patient, and inconsistencies with previous research, Phelps says, “I don’t think the authors were appropriately cautious.” However, she adds, “It could be the difference between their findings and ours is linked to when during development the amygdala lesion occurred in our respective patients.” Feinstein acknowledges that SM has injuries to other parts of her brain and these could have exacerbated the harm done to her amygdala to produce her unique immunity to fear.

Phelps also points out that SM has been “tested extensively and has some knowledge of her condition”. Perhaps she is overplaying her lack of fear, even subconsciously, to conform to the team’s expectations? Feinstein thinks that’s “highly unlikely”. He and his colleagues have never mentioned to SM that they’re focusing on fear. Their experiments largely involve a spectrum of emotions and they tell SM that they’re interested in emotion, memory and other general concepts. When explicitly asked, she said that they’re interested in how her brain damage affects her behaviour. More importantly, Feinstein says, “After over two decades of extensive testing with SM, we have been repeatedly impressed by her lack of insight into her specific fear impairments.”

Even SM’s case doesn’t imply that the amygdala is the brain’s fear centre. Feinstein thinks that it’s more of a “broker”, going between parts of the brain that sense things in the environment, and those in the brainstem that initiate fearful actions. Damage to the amygdala breaks the chain between seeing something scary and acting on it.

If that seems like a good thing, think again. In comic books, conquering fear is a good basis for a successful vigilante lifestyle. In real life, the consequences are far direr. As Feinstein writes, “[SM]’s behaviour, time and time again, leads her back to the very situations she should be avoiding, highlighting the indispensable role that the amygdala plays in promoting survival by compelling the organism away from danger. Indeed, it appears that without the amygdala, the evolutionary value of fear is lost.”