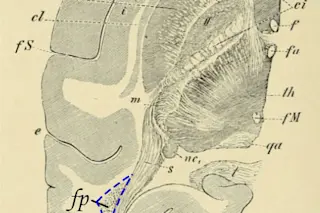

The vertical occipital fasciculus, or VOF, is identified in a postmortem human brain in 1909, but labeled with a different name. Knowledge of this piece of anatomy had fallen out of medical texts until recently. | Curran 1909

While examining colorful 3-D brain images, Stanford psychology graduate student Jason Yeatman spotted a part of the brain he’d never learned about in class. But what he thought was a discovery was actually a rediscovery — a snippet of brain anatomy lost to science for decades.

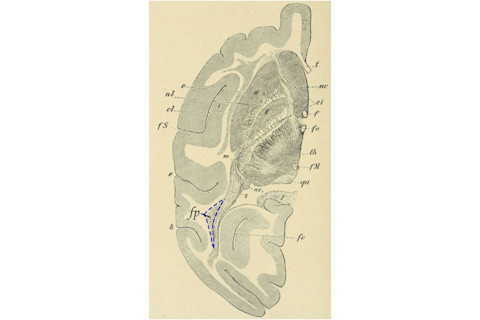

The vertical occipital fasciculus (VOF) debuted in an atlas by German psychiatrist and anatomist Carl Wernicke in 1881. It had all but vanished from scientific literature when Yeatman noticed it. He published his find of the VOF, a bundle of white-matter fibers near the back of the brain, in 2013 and helped show its involvement in reading.

Yeatman, now an assistant professor at the University of Washington, then enlisted fellow postdoc researcher Kevin Weiner to learn why the VOF fell out of sight. Their findings appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Weiner, now a Stanford researcher, recalls how they figured it out.

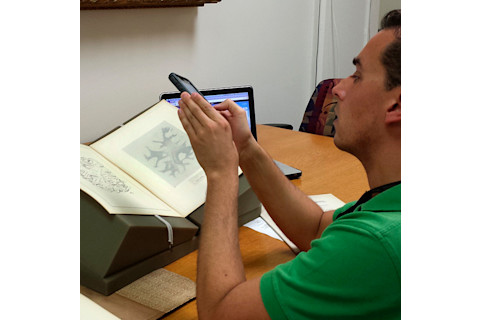

Kevin Weiner studies an 1897 brain atlas by Wernicke. | Jason Yeatman

In his own words:

I got bitten by the history-of-neuroscience bug a long time ago — I like looking at old papers. They’re written in a more colloquial manner. When Jason came to me, I immediately agreed, and it turned into a fun little journey. Every single name and date, every single atlas, led us to another name and date or another atlas or another paper. I would look at pictures and hack my way through the German.

An image of Carl Wernicke’s original 1881 identification of the VOF in the brain of a monkey. | Wernicke 1881

We saw decades’ worth of publications where scientists argued that the VOF didn’t exist. The most aggressive argument came in 1891, and it was based on the fact that it didn’t exist in a calf embryo! How is that logical? But it didn’t matter: Atlases afterward repeated this argument against Wernicke’s finding, which perpetuated doubt in the VOF’s existence.

Then we found a 1909 journal article with beautiful images of the VOF from dissections of dead human brains. It was so consistent with our images of living human brains. The author laid out a how-to list to find the VOF, and it became clear why others missed it: It is about half an inch from the surface of the brain. If you were rough with the brain during dissection, you could actually rip the VOF right off and never see it.

To make matters worse, there was a movement in the late 1890s and early 1900s to reduce the amount of anatomical names from 35,000 to 4,500. So thousands of anatomical structures were just written out of these atlases — and of history.

I can’t give you a number as to how many structures have been forgotten or overlooked, but this isn’t the only one. Our whole paper is about trying to evolve from what could be called poetic descriptions of anatomy to more computational approaches so that we can prevent this sort of thing. We built an algorithm to automatically identify the VOF from brain scans, and it works. People who downloaded it can see the VOF in every single brain! It’s really nice when that happens.