Many people may be living life without a particular brain region – and not suffering any ill-effects.

In a new paper in Neuron, neuroscientists Tali Weiss and colleagues discuss five women who appear to completely lack olfactory bulbs (OB).

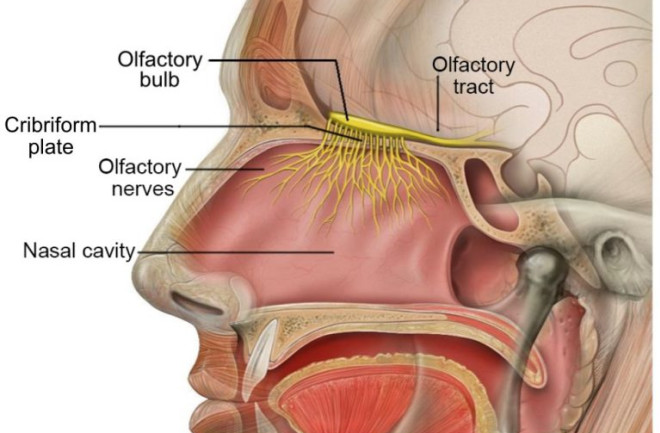

According to most neuroscience textbooks, no OB should mean no sense of smell, because the OB is believed to be a key relay point for olfactory signals. As Wikipedia puts it:

The olfactory bulb transmits smell information from the nose to the brain, and is thus necessary for a proper sense of smell.

Scent molecules activate olfactory receptors and signals travel up the olfactory nerves to the olfactory bulb, and then on to the rest of the brain via the olfactory tract. From Wikipedia.

However, remarkably, Weiss et al.’s five women seem to have entirely normal sense of smell despite lacking any visible OBs on brain MRI scans. On both subjective and objective measures of olfactory function, these women showed no abnormalities.

Weiss et al. came across two of the women serendipitously while carrying out MRI scans for an unrelated project. The other 3 were found among healthy controls in the Human Connectome Project MRI dataset.

Although Weiss et al. looked for men lacking OBs in the HCP dataset, they didn’t find any, suggesting that the condition might be more common in females. Most of the five women were left-handed, so left-handed women might be especially prone to being OB-free, although the sample size is small.

So what do these findings mean? The authors admit that their results are not easy to explain:

Humans can retain olfaction without apparent OBs, and we don’t know how they achieve this.

One potential explanation that Weiss et al. discuss is that humans may not rely on their OB in the same way as in other species such as rodents:

…coding mechanisms of human olfaction [might] differ from those in rodents, allowing for basic olfactory facets without OBs.

Yet the five women didn’t just possess a ‘basic’ sense of smell, but a fully functional one (as far as could be determined.)

Personally, the biggest question is this: where do the signals from the olfactory receptors in the nose go, if not to the OB? The easiest place for the nerve fibres to reach would be the frontal cortex, which normally sits just above the OBs. There is, indeed, evidence that a nose-to-cortex pathway can develop in rats with OB lesions. Unfortunately, there is no direct evidence of this in Weiss et al.’s paper and it might be too small to detect on MRI.

If the frontal cortex is serving as a surrogate OB in the OB-less women, it would be striking proof of just how plastic the cortex is. The OB is a unique brain area with complex circuitry including structures which don’t exist in the cortex. It would be remarkable if the cortex could ’emulate’ the OB’s function, but this does appear to be the simplest explanation of these fascinating results.