THE STUDY

“Identification of an Immune-Responsive Mesolimbocortical Serotonergic System: Potential Role in Regulation of Emotional Behavior,” by Christopher Lowry et al., published online on March 28 in Neuroscience.

THE MOTIVE

Some researchers have proposed that the sharp rise in asthma and allergy cases over the past century stems, unexpectedly, from living too clean. The idea is that routine exposure to harmless microorganisms in the environment — soil bacteria, for instance — trains our immune systems to ignore benign molecules like pollen or the dandruff on a neighbor’s dog.

Taking this “hygiene hypothesis” in an even more surprising direction, recent studies indicate that treatment with a specific soil bacterium, Mycobacterium vaccae, may be able to alleviate depression. For example, lung cancer patients who were injected with killed M. vaccae reported better quality of life and less nausea and pain. Now a team of neuroscientists and immunologists may have figured out why this works. The bacteria, when injected into mice, activate a set of serotonin-releasing neurons in the brain — the same nerves targeted by Prozac.

THE METHODS

Some studies have found that treatment with M. vaccae, the inoffensive soil bacterium, eases skin allergies, and other reports — such as the cancer study — show that it can improve mood. Christopher Lowry, a neuroscientist at the University of Bristol in England, had a hunch about how this process might work. “What we think happens is that the bacteria activate immune cells, which release chemicals called cytokines that then act on receptors on the sensory nerves to increase their activity,” he says.

To verify this hypothesis, he and his colleagues carried out a series of experiments on mice. First, Lowry killed and broke up M. vaccae with sound waves. He then anesthetized six mice and injected the pulverized bacteria directly into their windpipes. After killing the mice, he indirectly measured the levels of cytokines in the animals’ bodies and found an increased production of these proteins in their lung tissue.

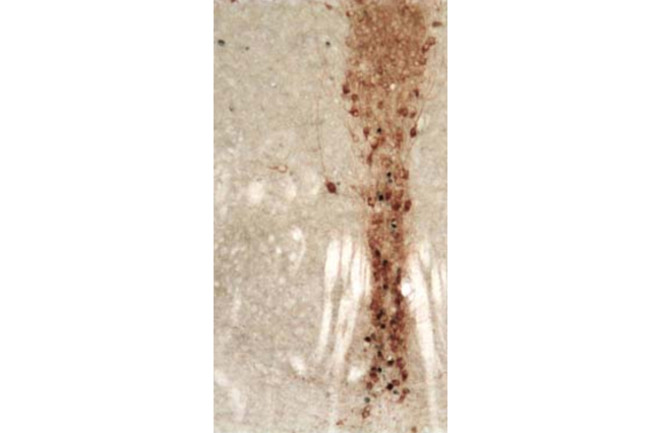

The team also looked at the mouse brains to see which neurons, if any, were activated after the bacterial injection. They found that serotonin-producing neurons in a specific region of the brain — the dorsal raphe nucleus — were more active in the treated mice. “That’s important,” Lowry says, “because cells in that part of the raphe project to parts of the brain that regulate mood, including the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, which is also involved in mood regulation and cognitive function.” They also found increases in serotonin itself in the prefrontal cortex.

Finally, Lowry and his colleagues studied another set of mice, who were subjected to a stress-response test. They dropped each mouse into water for five minutes and timed how long it would take the animal to switch from active swimming to passive floating. Control mice swam for an average of two and a half minutes, while the M. vaccae–injected animals paddled for four. Researchers already know that antidepressants increase active swimming and decrease immobility. The bacteria “had the exact same effect as antidepressant drugs,” Lowry explains.

THE MEANING

The results so far suggest that simply inhaling M. vaccae — you get a dose just by taking a walk in the wild or rooting around in the garden— — help elicit a jolly state of mind. “You can also ingest mycobacteria either through water sources or through eating plants — lettuce that you pick from the garden, or carrots,” Lowry says.

Graham Rook, an immunologist at University College London and a coauthor of the paper, adds that depression itself may be in part an inflammatory disorder. By triggering the production of immune cells that curb the inflammatory reaction typical of allergies, M. vaccae may ease that inflammation and hence depression. Therapy with M. vaccae — or with drugs based on the bacterium’s molecular components — might someday be used to treat depression.

“It’s not clear to me whether the way ahead will be drugs that circumvent the use of these bugs,” Rook says, “or whether it will be easier to say, ‘The hell with it, let’s use the bugs.’”