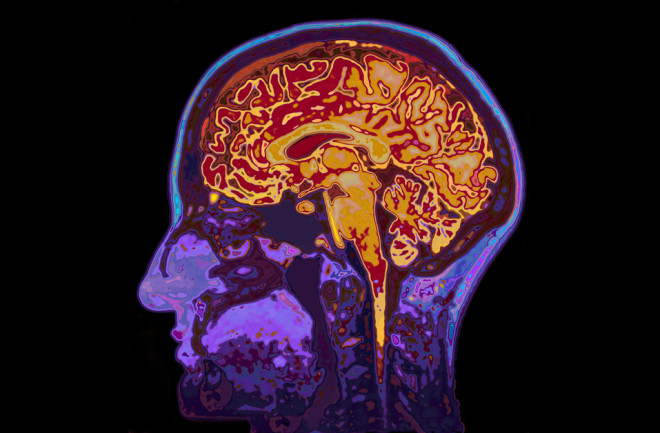

If you look at the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient, you’ll see clear and undeniable damage.

Clusters of dead nerve cells. Hard plaques cemented between cells and thick tangles of proteins twisted up inside the cells themselves.

These are the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s, and they drive the disease’s infamous symptoms, like memory loss, behavioral issues and problems thinking.

What Causes Alzheimer's Disease?

The majority of the damage comes from two specific proteins, beta-amyloid and tau. These protein-rich plaques and tangles degrade the brain beyond repair.

With brain imaging and other techniques, researchers have been digging into the roots of the proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease for decades. We now have a good idea of how they form, but it’s the why that’s missing.

But with brain imaging and early detection, researchers are now able to study these proteins long-term, watching them accumulate as the disease progresses. Many think that if we can watch them build up, we can find a way to break them back down — ultimately curing Alzheimer’s. That’s easier said than done, of course, because both tau and beta-amyloid proteins wreak havoc in their own, separate ways.

Read More: How Did Alzheimer's Disease Get Its Name: Who Discovered It?

What Are Beta-Amyloid Plaques?

While amyloid precursor proteins (APP) — beta-amyloid’s parent protein — are best known for their contribution to Alzheimer’s disease, they might not deserve such a bad rap. APP is abundant in the brain and is found in synapses, tiny bridges that allow neurons to pass chemical and electrical signals to one another.

While the main function of APP is unknown, some scientists think they help guide neurons through the brain during early development or help cells attach to one another. But whatever use our bodies have for APP, it can turn into a deadly problem under the right conditions.

“APP is produced in the brain and is normally metabolized by an enzyme called alpha secretase, which cuts it in half and flushes it out with no problems,” says Ronald Petersen, director of the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. “But in people who develop Alzheimer’s disease, instead of being cut by alpha secretase, APP is cut by two other enzymes — beta secretase and gamma secretase.”

Read More: What You Need to Know About the 6 Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

Beta-Amyloid Proteins in the Brain

When this happens, for reasons Petersen and other researchers aren’t exactly sure of, APP is chopped into strands of amino acids that the brain can’t metabolize, called beta-amyloid proteins.

Unable to break down, these proteins start sticking together, ultimately forming hard plaque deposits in the synapses between cells. Beginning in the hippocampus, these dense clusters block communication between neurons and kick-start cell death, triggering a loss of memory. And things only get worse from there.

Once beta-amyloid plaques begin to form, it seems to open the door to the accumulation of Alzheimer’s other hallmark protein: tau. Researchers aren’t sure why this is, but they do know that it’s a key turning point in neurodegeneration.

Read More: Can We Inherit Alzheimer's From Our Parents?

What Is Tau Protein?

Unlike beta-amyloid, researchers have a good understanding of tau and how it functions in the brain.

“Tau is a normal protein that exists in every cell in the body,” said Juan Troncoso, director of the Brain Resource Center at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Our cells’ overall structures are supported by microtubules, hollow tubes that give cells their shape. Along with another protein called tubulin, tau binds to these microtubules to keep them strong and stabilized.

Read More: A Tiny Discovery Could Revolutionize Research Into Neurodegenerative Diseases

Tau Proteins and Alzheimer's

But for reasons unknown, tau proteins in Alzheimer’s patients go through a process called hyperphosphorylation. Here, the addition of phosphate molecules causes tau proteins to break down and lose their shape.

Too weak to support microtubules, they begin detaching and sticking to each other instead. The degenerate tau proteins tangle together inside of neurons, growing large enough to block the chemical and electrical signals that travel toward the synapses and onto neighboring cells.

“That leads to the death of that neuron, and maybe the one next to it, and the one next to that one,” adds Petersen. “And if those neurons are in the memory part of the brain, then the person becomes forgetful.”

Unfortunately, becoming forgetful is only the beginning. As plaques and tangles spread from the hippocampus to the cerebral cortex, behavior, reasoning and language start to fade, too. This degradation continues until patients can no longer perform basic bodily functions, like eating and swallowing. The result is ultimately death.

Read More: Is Alzheimer's Disease Fatal, and How Does It Lead to Death?

Alzheimer's Treatments

As of now, treatments for Alzheimer’s are limited. There are a handful of drugs and lifestyle adjustments that can ease symptoms, and studies on fasting diets are starting to show early promise. But researchers are confident that tau and beta-amyloid proteins hold the key to untangling Alzheimer’s.

“Because they’re so prominent in microscopic examinations of the brain, they have become targets for potential therapies,” said Troncoso, who has spent decades studying the disease. “If you can remove or prevent the accumulation of beta-amyloid with a vaccine or an antibody, then you may prevent or slow down the development of the disease.”