Shutterstock

Neurosurgeons live for the “great saves.” Our specialty is accustomed to more than its share of depressing outcomes, from lives cut short by brain tumors to minds devastated by head injury. Any neurosurgeon relishes the opportunity for a great save — a total cure or a dramatic neurological reversal. The elation of such a moment helps inoculate the surgical psyche against gloomier endings.

So when Christine, a quiet woman in her 50s, walked into my office, I was pleased to recognize — after speaking with her for only five minutes — that I had a chance to relieve her of an agonizing affliction. She would be my next great save.

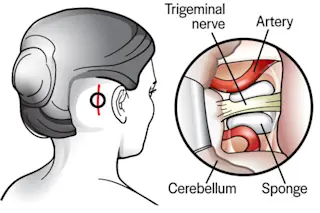

Christine had a relatively rare disorder called trigeminal neuralgia, and she had a severe case of it. This disorder, also known as tic douloureux (“painful tic” in French), can be so devastatingly painful that some call it “suicide disease.” ...