While reading The Founders of Evolutionary Genetics I encountered a chapter where the late James F. Crow admitted that he had a new insight every time he reread R. A. Fisher's The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. This prompted me to put down The Founders of Evolutionary Genetics after finishing Crow's chapter and pick up my copy of The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. I've read it before, but this is as good a time as any to give it another crack. Almost immediately Fisher aims at one of the major conundrums of 19th century theory of Darwinian evolution: how was variation maintained? The logic and conclusions strike you like a hammer. Charles Darwin and most of his contemporaries held to a blending model of inheritance, where offspring reflect a synthesis of their parental values. As it happens this aligns well with human intuition. Across their traits offspring are a ...

Why the future won't be genetically homogeneous

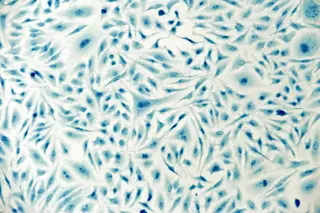

Explore how variation maintained in inheritance influences adaptation and challenges the blending model of inheritance.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe