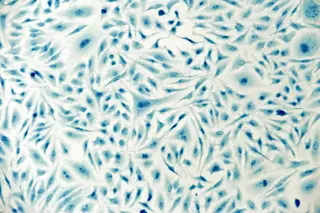

Elizabeth Blackburn is talking about chromosomes, which isn't surprising: She is the biologist who in 1978 first established that telomeres, caps on the ends of chromosomes, protect critical genetic material from eroding during cell division. Seven years later, she and molecular biologist Carol Greider discovered the enzyme telomerase. Both findings offer tantalizing clues to the mysteries of aging and cancer. In as many as 90 percent of metastatic cancers, for instance, telomerase is wildly over-expressed. Blackburn's work has launched one of the hottest fields in cell biology. Her office in the Blackburn Lab at the University of California at San Francisco is chockablock with awards; it also sports a poster depicting dancing chromosomes tipped with merry, Day-Glo telomeres.

What has Blackburn riled up at the moment, however, has nothing to do with her research. She is focused on the X's and Y's of chromosomes and why it is that more ...