The microbial “Ten Most Wanted” list includes some pretty shady characters: Escherichia Coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Neisseria meningitidis. Because these and other bacteria can cause serious illness — and even death — they tend to get all the attention. And we tend to think of all bacteria as bad guys.

But most bacteria aren’t harmful, and many are helpful — even necessary — to a healthy life. Without bacteria, we wouldn’t be able to digest certain foods or synthesize some crucial vitamins. Some bacteria even eat other microbes that do make us ill.

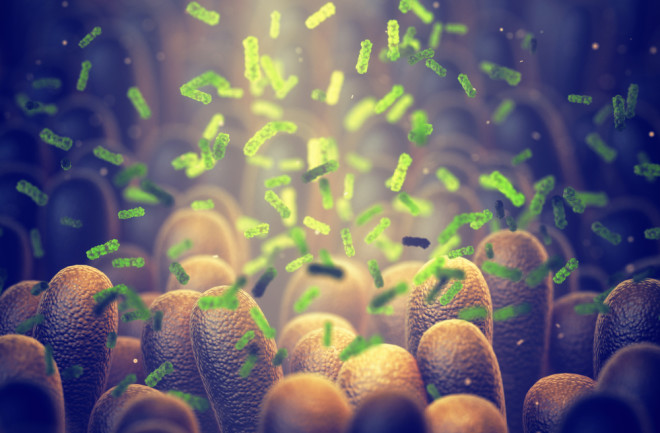

Even those few that can be dangerous often aren’t. And that’s a good thing, too. According to the latest count, we have at least as many bacterial cells in our bodies as we have human cells, maybe slightly more. And those tiny critters aren’t just passive passengers. Elaine Hsiao is a researcher at UCLA who studies how the microbiota affects the nervous system. In a 2015 YouTube video, she explains that these microbes interact with each other and form communities. “They divide and replicate” and “they even wage wars against each other,” she says. This drama is always going on within our bodies; however, we are unaware of most of it.

Better Negotiations

In many cases bacteria become dangerous only when their populations are disturbed — that is, when the microbial balance of our bodies is out of whack. In his 1974 book Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher, the physician and writer Lewis Thomas put it this way: “Disease usually results from inconclusive negotiations for symbiosis, an overstepping of the line by one side or the other, a biologic misinterpretation of borders.”

When bacteria do cause problems, however, those problems are not limited to what you typically think of as infectious disease. Microbes have been linked to a wide array of illnesses, including cancers, autoimmune illnesses, and even cardiovascular disease. But scientists are learning to work with bacteria to keep us healthy and even cure disease — in other words, to enhance those negotiations. As researchers better understand the human microbiome and new technologies enable us to alter individual microbes, it becomes possible to tinker with the microbiome in ways that promote and even restore health.

Nalinikanth Kotagiri is a researcher at the University of Cincinnati. He and his lab are working on a therapy for cancer that adapts the bacterium E. coli Nissle (not the strain of E. coli that causes illness) so that it secretes a substance that breaks down cancer cells, making it easier for the immune system to destroy the cancer.

These technologies work by engineering bacteria — either tweaking existing proteins or adding engineered proteins — that will reshape the immune system, helping it to do a better job fighting off illnesses such as cancer. “Unlike antibody-based drugs that we take only once we have a diagnosis, these engineered bacteria can be integrated into the microbiome that’s already there,” explains Kotagiri.

Kotagiri’s lab has recently received funding to work on bio-engineering the skin microbiome against environmental damage. This research will explore the feasibility of programming bacteria that naturally live on the skin to provide passive protection to prevent the development of skin diseases.

From Colds to COVID

Bacteria don’t have to be altered to be recruited as team members in fighting illness. Several studies looked at using Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus oralis to prevent recurrent upper respiratory tract and ear infections in children. Food allergies are also the target of bacteriotherapy research. There have even been clinical trials using oral bacteriotherapy to treat COVID-19.

Perhaps the most startling use of bacteriotherapy is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). In this therapy, fecal matter from a healthy person is placed in the colon of a patient whose gut microbiome is unhealthy and causing illness. As the name suggests, this approach essentially transplants the gut microbiome from a healthy person into an ill one. FMT can be accomplished by colonoscopy, enema, or orally (via a pill). While the treatment has had some ups and downs, it is now widely used for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, a potentially fatal infection that causes severe diarrhea and colitis, and is often the result of antibiotic treatments that have drastically altered the patient’s microbiome.

The bacterial communities that interact and wage war inside us usually do a pretty good job of keeping things running smoothly. But when things go wrong, this new research suggests, bacteria can also be important partners in healing.