It’s a recurring theme of the COVID-19 crisis: The virus sweeps its way through a community, and, despite being exposed to it in the same place at around the same time, people develop vastly different symptoms. Some barely feel anything — a scratchy throat, if that — while others spend weeks in the ICU with ravaged lungs, unable to breathe on their own.

These scattershot outcomes stem from wide variation in how our bodies respond to the virus. To mount the strongest defense, says Boston Children’s Hospital immunologist Hani Harb, the immune system must maintain a delicate equilibrium. “We need the balance of the force attacking the virus, and at the same time, a counterforce to say, ‘That's enough.’ ”

If anything interferes with optimal immune function, such as an errant gene, a lifestyle habit or a chronic condition, COVID-19 can wreak more havoc in the body than it otherwise would.

Genetic vs. Acquired

Among the main drivers of our innate immune response is a set of genes known as the HLA (human leukocyte antigen) complex. These genes code for proteins in the surfaces of cells that display signals to the immune system, and differences in these signals make the immune system react differently to invading pathogens. In this way, HLA genes affect our susceptibility to a host of illnesses, including viral ones. Scientists at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and elsewhere have found a particular HLA gene variant tied to high rates of severe symptoms of SARS, a coronavirus related to COVID-19.

Because COVID-19 only recently appeared in humans, we don’t know exactly which genetic quirks might make us more susceptible to it. Scientists are now investigating whether specific HLA genes give some people higher or lower degrees of protection against the virus. If they can identify such genes, companies could go on to create detection kits that would give test-takers an idea of how prone they may be to the illness.

But genes are only the first component of our COVID-19 response. So-called trained immunity is just as key in bolstering viral resistance, says Brianne Barker, an immunologist at Drew University. Our immune systems are far from immutable — they’re actually incredibly fluid, learning from the invaders they encounter and adapting their defenses accordingly. Some researchers speculate that if you’ve gotten other coronaviruses in the past, your immunity to COVID-19 might be somewhat higher, though by no means airtight.

Your lifestyle habits also shape your body’s reaction to the disease. COVID-19 uses a cell surface receptor called ACE2 to enter the cells that line your respiratory tract. New research shows that in smokers, these receptors are more prevalent, creating more potential access routes for the virus. “If you smoke,” Harb says, “the virus will be able to enter more cells in higher numbers.”

Taming the Storm

One of the biggest determinants of how sick you’ll get from COVID-19 is whether your body unleashes what’s known as a cytokine storm against the virus. After COVID-19 forces its way into cells, immune signaling proteins called cytokines act like warning sirens, bringing the body’s cellular attack force to the scene. Cytokines are “normally made in any immune response to recruit more immune cells or induce tissue repair,” Barker says.

Problems arise, however, when the body starts churning out too many cytokines, calling up a platoon of attacker cells equivalent to a D-Day invasion force. These out-of-control cytokines and marauding cells ravage healthy tissue, creating extensive lung damage that defies the body’s normal repair efforts.

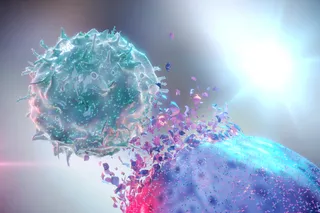

In most people with healthy immune systems, control cells called regulatory T cells help turn down the volume of attacker cells. These T cells’ purpose “is to keep everything quiet — see that all the [other] cells are functioning properly without being overstimulated,” Harb says.

But in some older people, or in those who have underlying immune deficits from chronic conditions, regulatory T cells do not function normally. When these people get COVID-19, cytokine storms may cause excessive inflammation in the lungs and whip up new torrents of attacker cells, leading to life-threatening disease. One Chinese study found that COVID-19 patients with severe illness had lower levels of regulatory T cells in their bloodstream. Children, on the other hand, may be less prone to disabling symptoms in part because their immune systems are better regulated and because they have fewer underlying conditions.

There might be ways to tame deadly cytokine storms that strike the vulnerable, Barker says. One cytokine in particular, called interleukin 6 (IL-6), can cause highly damaging inflammation, so researchers have started a clinical trial of an arthritis drug called tocilizumab — which blocks the action of IL-6 — to see if it can curb symptoms of COVID-19.

A safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine will ultimately be the best way to even the immune playing field for everyone. In the meantime, scientists will continue studying the broad range of immune responses to the virus — a still-muddled landscape in which rules seldom apply across the board. “I have seen patients over 70 who have the disease and they are fine, and there are many young, healthy people who are dying,” Harb says. “We have a lot to research. There is still a hidden component.”