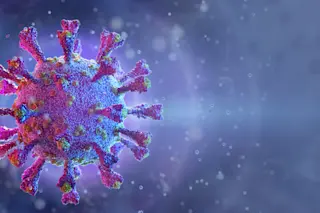

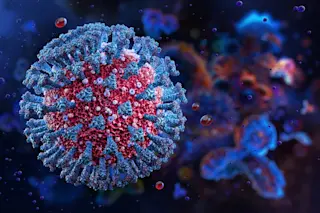

As the novel coronavirus infection known as COVID-19 continues to spread across the world — the number of confirmed cases in the U.S. crossed 15,000 on Friday — governments have made incredible efforts to limit the pandemic’s overall reach.

Yet there is also much uncertainty, and a fair amount of unscientific speculation, about the virus and its effects on people’s bodies. And some of COVID-19’s reported symptoms, like fever, cough and shortness of breath, overlap with those of everyday illnesses like strep throat, flu and the common cold.

Carl Fichtenbaum, an infectious disease specialist and professor of clinical medicine at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, says there’s still much that scientists don’t understand about how exactly this virus causes problems. “It’s very new, and we’re still trying to unravel it a little bit,” he says.

Here’s what some researchers and clinicians have learned so far about what the ...