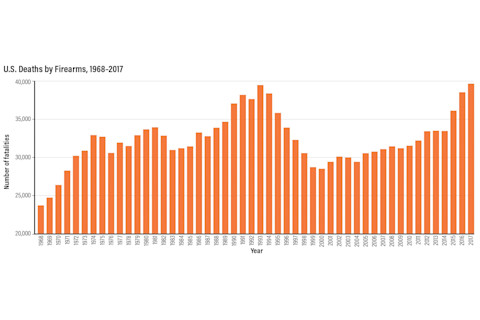

39,773: How many Americans lost their lives to firearms in 2017.

1.625 million: the number of Americans who have died from gunfire since 1968 — more than the accumulated American deaths from all wars since the country’s founding more than 200 years ago.

These are numbers that everyone agrees on. From here, nearly everything else that can be said about gun violence in the U.S. elicits a partisan response.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

A growing chorus of researchers wants to study gun violence in the U.S. as a public health issue, similar to the way they have tracked automobile or workplace safety for decades. Though limited by largely political obstacles around funding, experts including epidemiologists, social scientists and statisticians say that unbiased, peer-reviewed research is a missing piece of the gun violence discussion. Given the magnitude of the problem — not just in lives lost but in the consequences for survivors, families and entire communities — a purely scientific approach may hold the key to making progress toward reducing injuries and fatalities.

There’s one problem: Where to begin?

“We just don’t know very much,” says Andrew Morral, a behavioral scientist who leads a RAND Corporation initiative called Gun Policy in America. “We haven’t been investing as a country in research in this area in the same way that we have in motor vehicle accidents, for instance, where for [more than] 35 years we’ve had an entire agency devoted to that, collecting fantastic data. The result has been that motor vehicle accidents are [a] quarter of what they were at the time the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration was started.”

(Credit: Alison Mackey/Discover)

Alison Mackey/Discover

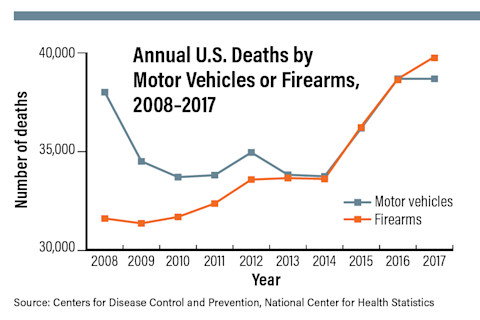

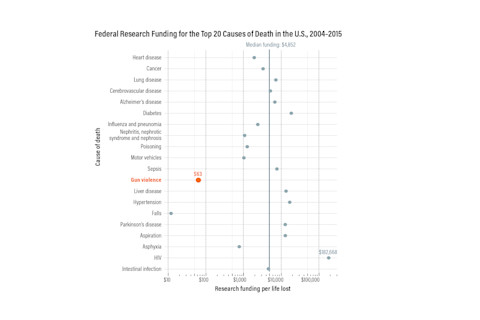

A 2017 JAMA study estimates that for every death due to firearms, the U.S. spends about $63 on research into the topic. In contrast, research spending on motor vehicle deaths is about $1,000 per fatality.

That disparity is particularly striking because the number of lives lost is similar: From 2008 to 2017, there were 342,439 deaths by firearm and 374,340 motor vehicle deaths.

As former congressman Jay Dickey wrote in 2012, “The United States has spent about $240 million a year on traffic safety research, but there has been almost no publicly funded research on firearm injuries.”

The reason, ironically, has Dickey’s name attached to it. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — the federal agency responsible for, among other things, researching and reducing injuries and violence — had long studied gun violence. But in 1996, Dickey submitted and helped pass the so-called Dickey Amendment, instructing that: “None of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.”

Over the last decade, 374,340 people in the U.S. were killed by motor vehicles, and 342,439 were killed by firearms. Despite the similar number of lives lost, research spending on motor vehicle deaths is nearly 16 times greater than on firearm-related fatalities. (Credit: Alison Mackey/Discover)

Alison Mackey/Discover

“The language did not ban research; it banned advocacy or promotion for gun control,” says Garen Wintemute, a physician and public health researcher who leads the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California, Davis Medical Center. “But everybody saw the writing on the wall, and CDC took itself out of the game.”

A 2003 provision to a Department of Justice appropriations bill, called the Tiahrt Amendment, dealt another blow: It prevented the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) from releasing firearm tracing data — how illegal firearms flow from manufacture, to sale, to use. Prior to Tiahrt, such data had been invaluable to academic research, says Morral.

“There was very useful scientific research going on looking at how guns flow between U.S. states as a function of how permissive state laws are in terms of gun violence,” says Morral. The ATF also provided research on “time-to-crime,” or the length of time between a gun’s purchase and its use in a crime. Such information could play a role in determining whether future policies achieve their desired results.

The impact of both Dickey and Tiahrt has been clear: From 1998 to 2012, the annual number of academic publications on gun violence dropped by 64 percent.

There have been small windows of renewed public funding for research on gun violence, such as a three-year period, started during the Obama administration, that has since closed. And private donations — such as $2 million that the Kaiser Permanente health consortium committed in 2018 to studying the issue— have kept other initiatives afloat. But the limited, disjointed efforts are no substitute for a long-term, concerted focus by a government agency like the CDC in tackling a complex problem.

Among the top 20 causes of death in the U.S., research funding varies widely. Funding for gun violence research receives $63 per life lost, the second lowest amount after falls. (Credit: Rand Corporation)

Rand Corporation

What We Know

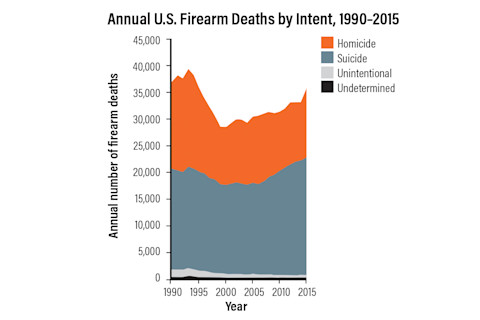

What we do know about gun violence in the U.S., from a purely statistical perspective, may surprise you. Mass shootings make headlines and dominate public discourse, but roughly 60 percent of firearm deaths in 2017 were suicides — that’s 23,854 people who took their own lives with a gun.

“Most of them are older, white men,” says Bindu Kalesan, an epidemiologist and data scientist at Boston University’s School of Medicine. In a 2018 study on suicide in the U.S. due to firearms, Kalesan found that the average American firearm suicide is a married, white male over 50, with physical health issues.

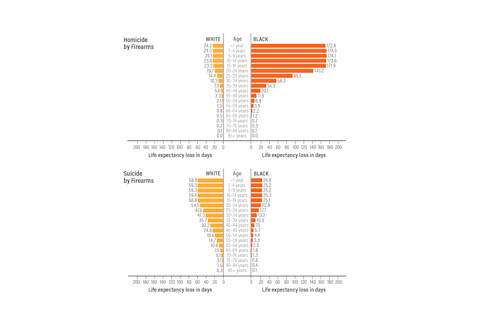

In a separate study, Kalesan discovered another demographic group taking the brunt of firearm-related loss of life expectancy: black men under age 20, who were dying from homicide. Because black male firearm homicides were much younger, on average, than white male suicides, the group’s life expectancy saw the bigger reduction, by more than four years.

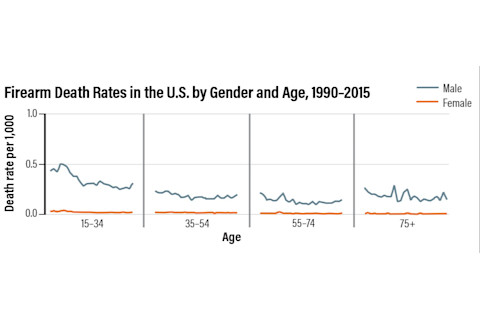

Women, meanwhile, make up around 10 percent of all U.S. gun deaths and, according to a study of 220 case histories published in the American Journal of Public Health, they are far more likely than men to be killed by an intimate partner. A 2014 review published in the Annals of Internal Medicine found some evidence that women with access to firearms are more likely to be victims of homicides than women without, possibly due to intimate partner violence.

(Credit: Alison Mackey/Discover)

Alison Mackey/Discover

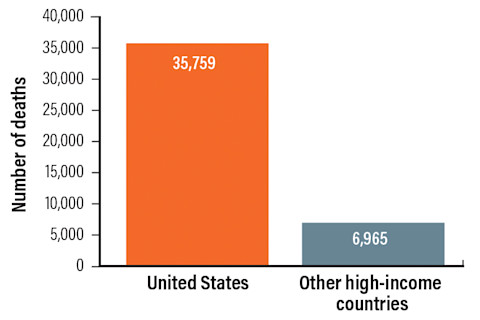

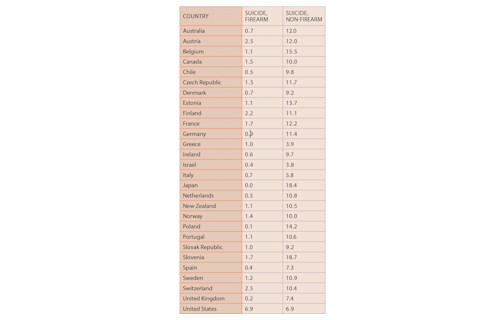

Overall, the rate of gun homicide is 25 times higher in the U.S. than in other high-income countries — for comparison, the rate of U.S. homicides due to causes other than firearms is only 2.7 times higher. And data from the FBI shows that handguns are by far the most likely type of firearm to cause a fatality. In 2017, handguns were used in 7,032 of the 7,886 firearm-related homicide deaths where the type of weapon was known; the type of gun was not recorded in data on roughly 3,100 additional homicides.

Perhaps most striking about the gaps in current gun violence data is how little we know about the shootings that don’t result in death. “If what you care about is state- or national-level gun deaths, homicides and suicides, we have good data,” says Morral. “We don’t have good data on firearm injuries, which represents the vast majority of firearm casualties.”

In fact, the CDC cautions that its own numbers on non-fatal firearm injury are “unstable and potentially unreliable” due to issues such as insufficient data. Even those imperfect numbers suggest an average of around 130,000 gun injuries per year.

And the number of non-fatal gun injuries is merely one unknown in a complex web of gun violence fallout. Individuals and their families may experience physical, psychological and financial repercussions, and so can the broader community. A neighborhood or city where gun violence is epidemic may also see lower property values, reduced tourism and less community engagement, says David Hemenway, director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center. For the most part, we don’t know the details — because they haven’t been studied.

(Credit: Alison Mackey/Discover)

Alison Mackey/Discover

A Matter of Public Health

The key to tackling firearm violence, Hemenway and peers say, is taking a science-driven public health approach. The method, as laid out by the CDC, is straightforward: define problems, identify risk and protective factors, develop and test prevention strategies, and assure their widespread adoption.

Hemenway explains the public health model in simpler terms: “Make it really hard to get sick and injured, and really easy to get healthy.”

There’s already a long history of using the tools of public health research to reduce injury, perhaps most dramatically with car safety. Since the 1950s, the per-mile fatality rate in the U.S. has fallen by 80 percent. The reduction is rooted in myriad sources, such as increased seat belt use, stricter penalties for drunken driving and new regulations for licensing. But robust data collection, overseen by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, is particularly important. NHTSA tracks everything from vehicular accidents involving fatalities to recalls and crash test results, all down to the smallest detail. Researchers analyze this data to discover common patterns, while lawmakers use it to measure the effect of legislation.

(Credit: Alison Mackey/Discover)

Alison Mackey/Discover

Graduated driver licensing — a multistage process for young drivers to become fully licensed — is a classic example. Researchers discovered that 16-year-olds had 10 times the risk of getting into a crash as older drivers; those accidents happened most often at night and while driving unsupervised with other teens. So states implemented a simple solution: Initially restrict newly licensed, young drivers from driving at night or alone with their peers. By 1997, all 50 states had implemented some form of graduated licensing, and results were often dramatic. In Michigan, for example, the crash risk for 16-year-old drivers fell almost 30 percent.

Such an impressive reduction in deaths thanks to the public health approach is not an outlier. For example, in the mid-1960s, more than 11,000 young children were poisoned by baby aspirin each year. Doctors, researchers and drug manufacturers took a multidisciplinary, public health approach, addressing drug flavoring and marketing, parent education, and dosing. The effort culminated in the Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970, when the U.S. mandated the medicine be sold in child-resistant packaging. Accidental baby aspirin poisonings of children younger than 5 dropped by an astonishing 70 percent three years after the change.

(Credit: Alison Mackey/Discover)

Alison Mackey/Discover

The public health approach can even save lives by analyzing data and identifying injury reductions that come about by happenstance. For instance, before England and Wales shifted utilities from domestic coal gas to natural gas in the 1960s and ’70s — an economic decision that by chance eliminated deadly carbon monoxide — inhaling oven fumes was the method of choice for 41 percent of all suicides in 1963. After the switch, it became nearly impossible. The overall suicide rate in the two countries dropped by 30 percent and never rebounded. Preventing suicide was an unintended consequence, revealed after the fact through public health data, but it showed what can happen when individuals contemplating the act lose an easy-access method.

Something similar may be possible when it comes to reducing gun violence.

For instance, public health researchers agree that suicide is typically an impulsive act, often aborted before completion — and that the majority of people who survive an initial suicide attempt never make a second try. As shown in England and Wales, when an immediately accessible, highly effective means of suicide is no longer available, the overall suicide rate may drop.

In the U.S., the limited data available suggests that only about 13 percent of all suicide attempts succeed. However, up to nearly 90 percent of attempts using firearms result in death.

The link between gun availability and suicide has already been studied in other countries. In the early 2000s, Swiss army reforms halved the number of soldiers, which also reduced the number of firearms kept in homes. Before the reduction, the suicide rate among 18- to 43-year-old men had already been falling. But researchers observed the rate dip sharply immediately after the reform, and then continue its gradual downward trend.

Around the same time, a similar phenomenon happened in Israel, which began requiring soldiers to leave guns on base during weekend leave. After the policy change, suicide among 18- to 21-year-old soldiers fell by 40 percent annually. The authors of a 2010 study on the policy’s consequences observed that a reduction in weekend suicides, rather than during the week, was responsible for nearly the entire drop in deaths.

The Big Takeaway

While relatively minor reforms, such as those in Israel and Switzerland, can have significant impact on suicide prevention, the effects of policies on broader gun violence issues are often far more complex and difficult to assess. Morral’s team at RAND combed through the limited scientific literature on firearm policy in the U.S. to see which types of laws have the strongest evidence of reducing death and injury.

In the U.S., only about 13 percent of all suicide attempts succeed. However, up to 90 percent of attempts using firearms result in death.

Their analysis found that only child-access prevention laws, such as those that require keeping guns at home safely locked, met their highest evidence-based standard for reducing injuries and deaths, and then only in children. The team found moderate evidence supporting the prohibition of gun ownership among people with mental illness or specific mental health histories. They also turned up moderate evidence that so-called “stand-your-ground” laws actually increased homicides. These types of laws vary by jurisdiction and can refer to a right to defend oneself, others or property with lethal force, rather than seeking safe retreat.

Morral warns that a lack of evidence doesn’t necessarily mean a given policy is ineffective. In many cases, the research either hasn’t been attempted or comes from small studies based in different states with disparate laws and other variables. For instance, there’s moderate evidence that background checks — mostly those that occur at a dealership rather than private sales — reduce firearm suicides and homicides. But there is only limited evidence that they reduce overall suicide and homicide rates: It’s unclear how many individuals use a different method to end their lives or someone else’s if prevented from using a gun. There’s also simply too little data to determine the effect of universal background checks, which would include all firearm transfers, not just those that occur at dealers.

“There’s a whole lot of policy effects that haven’t been studied,” Morral says, adding that many of the policies he and his colleagues looked at simply had no supporting research that met their standards for determining cause-and-effect. “I really regard that as one of the big takeaways.”

Among the most glaring gaps in current gun violence research: “The reason people buy handguns today is to defend themselves,” says Morral, “and we don’t know what the facts are around that.”

For example, his team found evidence-based research in support of child-access prevention laws saving children’s lives. But Morral says there have not been sufficient studies on how those same laws may affect other firearm-related issues, such as whether deaths increase or decrease when a childproofed gun is involved in a legitimate act of self-defense. It’s difficult to determine the full impact of such laws, positive or negative, when most of their consequences remain unknown.

Another major issue, says Morral, is that most available research is built on existing, open access databases compiled by government agencies such as the CDC. Researchers tapping into that data have no say over what information is collected or how. Instead of being able to design rigorous, controlled studies, they typically have to dig through someone else’s raw data, hoping to find correlations.

“Ambitious projects that cost money have been very, very difficult to do for the last 20 years,” Morral says.

(Credit: Harry Campbell)

Harry Campbell

There have been exceptions. In January, the American Journal of Public Health published a study on gun violence in some of Philadelphia’s high-crime neighborhoods. Researchers divided more than 100 geographic clusters of vacant, blighted lots into three randomly selected groups. Within each group, the vacant land received either light intervention (trash was collected and grass mowed), significant intervention (the lots were transformed into parklike settings with trees and new grass) or no intervention.

The experiment lasted nearly two years, and researchers found a significant reduction in gun violence in the geographic clusters with vacant land that had been improved in any way. What’s more, there was no evidence that shooting incidents moved from those improved clusters to adjacent areas.

Another study underway in California will measure what happens when current firearm owners are later prohibited from possessing a firearm, after, for example, committing a crime or receiving a specific mental health diagnosis. Researchers will be able to track outcomes in randomly assigned jurisdictions that give owners different amounts of time to surrender their guns.

These are the sorts of studies that Morral says have significant potential to help us better understand gun violence in America.

It’s a sentiment that Jay Dickey, who died in 2017, might have shared. As he neared the end of his life, Dickey advocated, with increasing vehemence, for a return to the very sort of research his 1996 amendment had halted. As he wrote in 2012, comparing gun research to the proverbial question about when to plant a tree: “The best time to start was 20 years ago; the second-best time is now.”

Russ Juskalian is a freelance journalist and photographer based in Munich, Germany. This story originally appeared in print as "The Science of Gun Violence."