Vaccines were once thought of as an axiomatic good, a longed-for salvation in the form of a syringe, banishing crippling and deadly infections like polio, smallpox and tetanus. But within the past few decades we have seen the emergence of anti-vaccination movements and a rise in cases of childhood diseases that are entirely preventable with a quick jab to the arm.

Over the past five years, outbreaks of mumps, measles and whooping cough have cropped up throughout the country. And then, of course, there is widespread skepticism among the general public on influenza and the merits of a seasonal flu shot. Even as outbreaks of avian and swine flu have periodically emerged in this country, there are still people who resist vaccination against the flu. This seemingly pervasive opposition to flu vaccination is not without its historical and sociological roots.

Some of the American public’s hesitance to embrace vaccines — the flu vaccine in particular — can be attributed to the long-lasting effects of a failed 1976 political campaign to mass-vaccinate the public against a strain of the swine flu virus. This government-led campaign was widely viewed as a debacle and put an irreparable dent in future public health initiatives, as well as negatively influenced the public’s perception of both the flu and the flu shot in this country.

In the late winter of 1976, a completely novel strain of influenza was causing hundreds of respiratory infections at Fort Dix, an army post located in central New Jersey. Initially, this virus appeared to be closely genetically related to the 1918 flu pandemic that killed over a 100 million people globally, a pandemic that shared the very same Fort Dix as one its points of origin. These striking coincidences, along with the virus’s “sustained person-to-person spread,” prompted global public health officials to start planning for what could conceivably burgeon into a series of large and deadly outbreaks, if not an actual pandemic, in the upcoming winter (1).

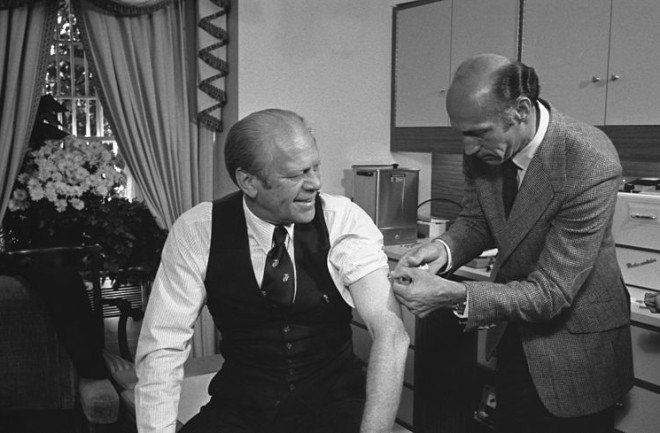

But while the World Health Organization adopted a cautious “wait and see” policy to monitor the virus’s pattern of disease and to track the number of emerging infections, President Gerald Ford’s administration embarked on a zealous campaign to vaccinate every American with brisk efficiency. In late March, President Ford announced in a press conference the government’s plan to vaccinate “every man, woman, and child in the United States” (1). Emergency legislation for the “National Swine Flu Immunization Program” was signed shortly thereafter on April 15th, 1976 and six months later high profile photos of celebrities and political figures receiving the flu jab appeared in the media. Even President Ford himself was photographed in his office receiving his shot from the White House doctor.

Within 10 months, nearly 25% of the US population, or 45 million citizens, was vaccinated, but serious problems persisted throughout the process (2). Due to the urgency of creating new immunizations for a novel virus, the government used an attenuated “live virus” for the vaccine instead of a inactivated or “killed” form, increasing the probability of adverse side effects among susceptible groups of people receiving the vaccination. Furthermore, prominent American scientists and health professionals began questioning the campaign’s large expense and its drain on scarce public health resources (2).

With President Ford’s reelection campaign looming on the horizon, the campaign increasingly appeared politically motivated. The rationale for mass vaccination seemed to stem from only the barest of biological reasoning — it turned out that the flu wasn’t even related to the virus that caused the grisly 1918 epidemic and, indeed, those who were infected with the flu only suffered from a mild illness while the vaccine, for the reasons stated above, resulted in over four-hundred and fifty people developing the paralyzing Guillain-Barré syndrome. Meanwhile, outside the United States’ borders, the flu never mushroomed into the anticipated public health disaster. It was the pandemic that never was. The New York Times went so far as to dub the whole affair a “fiasco,” damning one of the largest and probably one of the most well-intentioned public health initiatives by the US government (1).

As the historian George Dehner wrote in his 2010 review on the lessons learned from the 1976 flu response,

The Swine Flu Program was marred by a series of logistical problems ranging from the production of the wrong vaccine strain to a confrontation over liability protection to a temporal connection of the vaccine and a cluster of deaths among an elderly population in Pittsburgh. The most damning charge against the vaccination program was that the shots were correlated with an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with an obscure neurological disease known as Guillain–Barré syndrome (1).

The American public can be notably skeptical of forceful government enterprises in public health, whether involving vaccine advocacy or limitations on the size of soft drinks sold in fast food chains or even information campaigns against emerging outbreaks. The events of 1976 “triggered an enduring public backlash against flu vaccination, embarrassed the federal government and cost the director of the U.S. Center for Disease Control his job.” It may have even compromised Gerald Ford’s presidential re-election as well as the government’s response to a new sexually transmitted virus that emerged only a few years later in the early ‘80s, killing young gay men and intravenous drug users. What happened in 1976 is a cautionary public health tale, the story of a vaccination quagmire that still resonates in the public psyche and in our discussions about vaccines today.

Of the 45 million people vaccinated against the 1976 swine flu, four hundred and fifty people developed the rare syndrome Guillain-Barré. From the CDC,

In 1976 there was a small increased risk of GBS following vaccination with an influenza vaccine made to protect against a swine flu virus. The increased risk was approximately 1 additional case of GBS per 100,000 people who got the swine flu vaccine. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) conducted a thorough scientific review of this issue in 2003 and concluded that people who received the 1976 swine influenza vaccine had an increased risk for developing GBS. Scientists have multiple theories on why this increased risk may have occurred, but the exact reason for this association remains unknown.

It is important to keep in mind that severe illness and death are associated with influenza, and vaccination is the best way to prevent influenza infection and its complications.

Resources

“No one can predict with absolute certainty what future directions pandemic influenza might take, but we would be ill-served if we did not consider past experience.” Check out this 2009 paper from the UPMC Center for Health Security examining the “Public Health and Medical Responses to the 1957-58 Influenza Pandemic.”

An incredible factoid about President Gerald Ford from the NYT’s blog The Sixth Floor: Ford ate the same, gag-inducing lunch everyday: “Day in and day out, Mr. Ford eats exactly the same lunch — a ball of cottage cheese, over which he pours a small pitcherful of A-1 Sauce, a sliced onion or a quartered tomato, and a small helping of butter-pecan ice cream. “Eating and sleeping,” he says to me, “are a waste of time.”

How are flu vaccines made? Well, some are made using 1,200,000,000 chicken eggs.

Getting the flu shot may provide protection against heart disease, heart attacks and strokes.

September is National Preparedness Month and October marks the beginning of flu season. So why not kill two birds with one stone and get your flu shot? Use Healthmap’s Vaccine Finder to locate a pharmacy near you to be prepared for this year’s flu season.

References

1) G Dehner (2010) WHO Knows Best?: National and International Responses to Pandemic Threats and the “Lessons” of 1976. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 65(4): 478-513

3) R Krause (2006) The Swine Flu Episode and the Fog of Epidemics. Emerg Infect Dis. 12(1): 40-3