By the time he reached Los Angeles, Landry was scared, dazed and exhausted. Flying for the first time in his life, the 13-year-old from Cameroon was now some 8,200 miles from all things familiar.

Landry, whose parents had recently died in a car crash, came to LA to live with his legal guardian. Although Aunt Delphine welcomed him warmly, Landry’s first night in America was restless. His left ankle was puffy and warm.

He settled in to his new environment, attending school and studying English while speaking French and Cameroonian pidgin at home. He played soccer and watched YouTube videos on his cellphone. But his ankle and lower leg continued to swell on occasion.

“In the hospital where I work,” Delphine, a certified nursing assistant, told Landry, “elderly people can have blood clots that make their limbs swell. But in someone your age, that doesn’t make sense. The next time this funny thing happens, please tell me tout suite, and I’ll take you to a clinic.”

Sure enough, Landry’s symptoms returned, and Delphine cajoled a local doctor into ordering an MRI of her nephew’s leg. But the swelling was gone by the time the scan was performed.

The doctor shrugged. He wasn’t convinced that Landry’s swelling was real. Plus, the boy’s remark about something under his skin sounded downright bizarre. Was Landry suffering from depression? Grief? Culture shock?

Creepy Crawler

A week later, Delphine asked the clinic to perform a routine blood test to rule out an elevated white blood cell count, which might suggest an infection. The result was so surprising, the lab called back the next day.

Although Landry’s total white count was fine, his array of cells was not. Instead of the usual distribution, more than 60 percent were eosinophils, a type of white blood cell that normally lives in tissue rather than blood. Although scientists still don’t fully understand how eosinophils help sustain health, in certain diseases they surge, spill into blood and release toxic proteins.

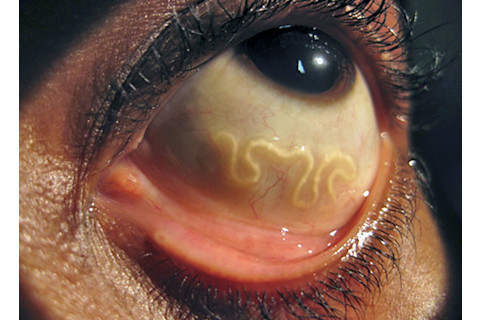

Once inside a human, the worm sometimes crosses the eyeball. | Lichtinger et al./The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Feb. 4, 2011

Doctors must consider many diagnoses for people with excess eosinophils. In a small percentage of patients, cancer, leukemia or a rare inflammatory disease may drive bone marrow to overproduce this type of cells. A far more common cause is an allergy to a pollen, chemical or drug. But even when suffering an allergic crisis, people normally don’t have Landry’s elevated level of eosinophils.

Another possibility is a parasite, a broad category of infectious agents that are commonly transmitted in the tropics, including in Cameroon. Of all the parasites that trigger a massive outflow of eosinophils, migrating worms — literally worms that travel through blood, tissues and organs — top the list.

Could one of these multicellular creatures and its offspring reside within Landry? And if so, what type? Dr. Kadesadayurat, a local pediatrician treating the teen, reached out to me for advice.

“What are we missing?” she asked. “What test should we run next?”

She had already excluded several tropical worms, including common gut parasites such as hookworm and roundworm; an intestinal invader known as Strongyloides; and Schistosoma, a leaf-shaped parasitic flatworm acquired by contact with water fouled by human waste.

But what about worms transmitted by an insect bite? Dr. K hadn’t mentioned those exotic foes. I suggested she ship Landry’s serum to a special lab at the National Institutes of Health. Several weeks later, my suspicion was confirmed. Crawling inside Landry was a worm exclusive to West and Central Africa: Loa loa.

Bite of a Fly

In 1979, I was a rookie doc at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London, a crumbling structure straight out of a Dickens novel.

Every week I met patients from different parts of the world. One of them was an African woman with unusual complaints.

She had originally told her general practitioner that her limbs sometimes swelled, that something was crawling in her skin, and that once or twice a transparent worm had slinked across her eye. Her doctor thought she was suffering from delusions and sent her to a psychiatrist.

L. loa is transmitted by certain species of deerflies. | Magne Flåten via Wikimedia

Months later, I saw her at the London hospital. She had high levels of eosinophils, and her blood contained microscopic larvae of L. loa, a threadlike worm that initially enters humans via the bite of a parasite-laden fly. But not just any fly. The worm is transmitted only by certain species of deerflies.

These cagey insects know how to find a meal. After breeding in mud along shaded streams, they fly high above the ground in search of warmblooded animals. Specific activities attract them — for example, animal motion, breath exhalations and even rising puffs of woodsmoke. Target found, they dive-bomb and bite their quarry in order to siphon a small amount of blood. Some bites can transmit an early stage of loa.

Months later, the larvae introduced by bites become mature worms that freely roam beneath their hosts’ skin, sometimes traveling up to 1 centimeter per minute and causing brief periods of swelling. Adult worms have also been known to cross the eyeball during their travels through the body. After mating, females give birth to new waves of offspring that live in the blood.

Today the parasite remains a health problem, inhabiting roughly 12 million people, mostly living in Africa’s backcountry.

Road to Recovery

Once Dr. K learned that Landry’s blood tested positive for loa, she called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to obtain diethylcarbamazine, or DEC. The medicine is used to treat specific parasitic infections and can kill loa in its adult and larval stages.

Landry was admitted to a hospital to begin treatment using DEC, low-dose steroids and allergy medications. After two days of treatment, I visited him and his indefatigable aunt on the ward. The medicines appeared to be working. According to the morning’s lab work, Landry’s eosinophil count had already gone down.

“Yes, thank you, I am feeling fine,” he said in a musical lilt as Delphine beamed. She smoothed her rumpled clothes after spending the night on a bed in the room.

“And how is school and life in LA?” I continued. “I’m sure you also miss home.”

“He’s doing very well in English,” Delphine interjected as the teen nodded. He then described several happy summers spent in his grandparents’ Cameroonian village by a river thick with flies.

For the rest of the day, I periodically thought of Landry. I imagined all he had left behind in his former country, and all that now lay ahead for him in America.

[This article originally appeared in print as "Something Within."]