In January, scientists discovered a potential new class of antibiotic — by digging through dirt.

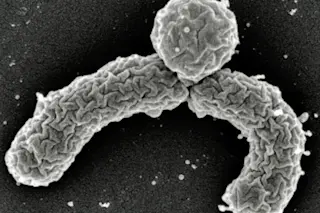

Soil microorganisms secrete much-desired antimicrobial compounds that yield novel drugs, but they’re fickle: Ninety-nine percent of microbial species won’t grow in labs. So Kim Lewis’ team at Northeastern University in Boston devised a method to isolate microbes in their natural environment to test their therapeutic potential.

After screening more than 10,000 soil bacteria samples, they identified Eleftheria terrae, which deploys the chemical teixobactin. In tests on mice, teixobactin obliterated drug-resistant bacteria — and target cells didn’t develop resistance to it. In fact, Lewis says it’s unlikely bacteria could engineer defenses against teixobactin within 40 years, if at all.

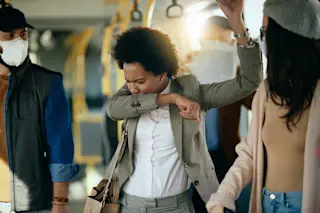

The timing couldn’t be better. Unless our antibiotics arsenal expands, drug-resistant infections could kill more people globally than cancer by 2050, some experts say.

It will be a few years before teixobactin moves to human trials, but ...