The flight from Addis Ababa to Chicago was full of terrors: the rush and noise of takeoff and landing, bumps over the Atlantic, the unfamiliar etiquette of the flight attendants. But for Mariam, the greatest turbulence was mental. She had cancer, and the best doctors in Ethiopia had told her that her disease was hopeless, too extensive to treat with their outmoded radiation machines and inadequate surgery. Go to America, they had told her. Go to the land of promises. Friends in America had made it possible for her to emigrate for treatment, but in her heart she doubted if anything could save her.

Only 35 years old and with nothing to lose, Mariam arrived on Christmas Eve and came straight from the airport to the emergency ward at Cook County Hospital. Residents crowded around her. Their exams compounded her fear with shame, because her cancer infiltrated the tissues of her vulva, swelling and distorting the most private parts of her body. She was in pain, weak with fever, uncomfortable, and lost in a world of English.

As the gynecologic oncologist who first saw Mariam, I was tempted to agree with my African colleagues— her prognosis looked bad. Conventional therapy for vulvar cancer is surgical: Remove the cancer along with a margin of the surrounding normal skin as well as the lymph nodes in the groin where the cancer might spread. The procedure is hazardous at best. In Mariam's case, all the tissues were raised, woody, and rough, and the lymph nodes had invaded the tissues of her legs and abdomen. Surgery would have required cutting away everything from her thighs inward, up toward her bladder, vagina, and rectum. In the past decade, treatment for advanced vulvar cancer has progressed. By combining chemotherapy with radiation, we can shrink massive cancers, allowing for less extensive surgery. In some cases, the cancer disappears and with it the need for any surgery at all. That approach seemed Mariam's only hope.

But cancer treatments, especially potentially toxic ones such as chemotherapy and radiation, require a clear-cut diagnosis. Mariam's condition was perplexing. Her cancer had progressed so far that I could not identify a clearly defined center. Her white blood cell count, which should have been high in response to infection and stress, was low, a sign of immunodeficiency. On top of all this, just before she left Ethiopia, Mariam's jaw had erupted with what her doctors thought was an abscess, and every evening shaking chills accompanied her spiking fevers.

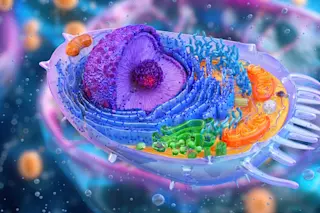

For more than 100 years, the key to cancer treatment has been histopathology, the microscopic examination of malignant tissue. Different types of cancer respond to different treatments differently. Cancers can be categorized based on their appearances, the ways they take up stains, the shapes and sizes of the cells, the size of the nuclei and the contents of the cytoplasm, and whether the cells group in clusters or sheets. Pathologists have made advances with dyes, electron microscopy, and the use of special antibodies to identify malignant tissue, but the dogma remains: Never begin treatment before the final pathology report comes back.

That's because even the most typical cancers might be something unsuspected. Ovarian tumors might have originated in occult cancers of the breast, stomach, or colon. Cervical tumors might be innocuous but overgrown warts. In Mariam's case, her biopsy report from Ethiopia labeled her cancer as a squamous malignancy, arising from the skin rather than from less common sources, such as sweat glands. To confirm the diagnosis, we performed a biopsy, slicing a wedge of tissue from the edge of the cancer.

It took seven days to get the report back. Mariam waited silently, but her friends were vocal.

"Why wait?" they asked. "You see how she is suffering. It's Christmas: Show some compassion." Treat her, they urged.

I did not, and our bedside meetings were strained. The strain grew when I requested that Mariam consent to HIV testing. She cried. In Ethiopia a diagnosis of AIDS is an immediate death sentence, because the antiretroviral drugs that have revolutionized HIV care in developed countries are not available. Mariam's friends were outraged.

"There is no reason for testing. She came here for cancer treatment, not AIDS. She has never used drugs. She is a married woman, and faithful."

Unfortunately, monogamy doesn't protect against HIV infection unless it's mutual. Mariam's HIV test came back positive. That wasn't surprising: Squamous cancers of the cervix and vulva appear to be more common in women with HIV, especially in women Mariam's age.

What was surprising were the biopsy results— both from her vulva and from the mass in her jaw that the oral surgeons drained. Mariam had lymphoma.

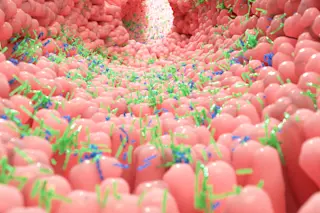

Lymphomas are cancers of the lymphatic tissue— the lymph nodes where immune cells gather and exchange signals. In this case, the source cells were B cells, which make antibodies that help corral pathogens for destruction. And this lymphoma was an unusual type.

Most lymphomas arise from genetic mutations in lymphocytes. Many occur in older patients. But over the past two decades, a rare type— Burkitt's lymphoma— has become more common. It's named for the doctor who found it cropping up in an African tribe as if it were an infectious disease. Burkitt's lymphoma later proved to be derived from an infectious organism. Epstein-Barr virus somehow enters lymphocytes and causes them to grow out of control. It is the same virus that causes infectious mononucleosis, or kissing disease.

Ordinarily the immune system kills lymphocytes infected with Epstein-Barr. But in immunosuppressed patients, especially those with HIV, infected lymphocytes persist. The virus drives the cells to multiply, and as they divide, genetic mutations occur. Normal growth-controls disappear. The cells become malignant.

The chemo-radiation used to treat skin cancers is the wrong therapy for lymphomas. But neither Mariam nor her friends seemed to believe us when our team outlined the diagnosis for her and the importance of chemotherapy and antiretroviral treatment. They refused transfer to the HIV ward.

"Mariam doesn't have AIDS," her friends insisted. "She has cancer. She should be with the cancer patients."

So we transferred her to the medical wards. The hematologic oncologists, the ones who specialize in cancers of the blood, took over. We followed Mariam from a distance as she began a powerful combination of antiretroviral therapy and chemotherapy.

Lymphomas grow rapidly. Mariam's cancer had appeared in only a few months. Once the chemotherapy began, it shrank away even faster. Three days after chemotherapy, as the mass in her jaw dissolved, she could eat solid food again. Her fever faded away. The enormous tumor in her vulva broke up into islands of cancer. And then it disappeared.

The outlook for HIV-infected patients with lymphoma is guarded. Those lymphomas not caused by Epstein-Barr respond poorly to chemotherapy, relapse quickly, and end in death. But if antiretroviral therapy controls the HIV infection, the immune system may take control of Burkitt's lymphomas. Mariam's helper CD4 cell count, a measure of the capacity remaining in her immune system, was low but not desperately so. Though our experience is still limited, some patients like her have lived for years with both their lymphomas and their HIV infections in remission.

Mariam is home from the hospital now. I saw her the other day in the HIV clinic, picking up a prescription for antiretroviral therapy. Her smile is still awkward, but her eyes are clear, as the terror and hopelessness that she flew with from Addis Ababa are gone.