Most people don’t even know they have a pancreas, let alone what it does. One of my patients, Richard, was no exception. He came to see me after experiencing several months of weight loss and fatigue.

A CT scan revealed a concerning spot on his pancreas as well as other spots on his liver, and a biopsy confirmed our worst fears: He had pancreatic cancer. The spots on his liver also were pancreatic cancer cells, indicating the cancer had spread, or metastasized, to another organ. Richard’s cancer was advanced and likely to result in his death.

In more than two decades as a doctor, I’ve diagnosed more than 1,000 patients with pancreatic cancer, and giving this kind of news is never easy. Richard was 65, had just retired a few months earlier and was looking forward to spending time with his grandchildren. When I called him with his results, he was understandably devastated. I marveled once again at the destructiveness of this disease.

Pancreatic cancer — pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma — is the most common tumor of the pancreas and has the worst prognosis. Within five years of diagnosis, 95 percent of patients die of the disease. Yet researchers are finally making some headway by studying how to harness the power of the body’s own immune system to extend, by even a few months, patients’ lives.

The pancreas itself is about 6 inches long and tucked away behind the stomach and small intestine. It pumps out hormones such as insulin, which helps to regulate blood sugar levels, in addition to enzymes that allow us to digest food. When cells start going awry, catching cancerous growths early is nearly impossible. The symptoms — jaundice, weight loss and pain — often develop late in the course of the disease, usually too late for effective treatment with surgery. The risk factors for pancreatic cancer are numerous but some major ones include tobacco use, chronic pancreatic inflammation, obesity and simply being older than 60. Obviously, not all of these risk factors can be controlled.

The organ’s location ensures its intimate relationship with many of the key blood vessels that course through the abdomen. So when pancreatic cancers either spread to other organs or become intertwined with some of these vessels, surgery is off the table. Even among those who do undergo surgical removal of the cancer, recurrence is common, with as many as 60 percent seeing the disease return within six months.

That’s why even in 2017 most patients with pancreatic cancer are left with medical, rather than surgical, treatment options. Often, that medical treatment becomes purely palliative, meaning we manage the growth of the cancer and its effects on the body as well as we can, but we don’t expect to cure the disease.

Resistance is the Rule

Chemotherapy has emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for pancreatic cancer patients. It extends life by months or years and can improve quality of life. Drugs like fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and irinotecan work by mimicking and damaging DNA molecules, or inhibiting enzymes involved in cell and DNA replication, slowing the uncontrolled growth of tumor cells. Another common and newer drug used to treat pancreatic cancer is gemcitabine, which also mimics one of the building blocks of DNA and interferes with the ability of cancer cells to reproduce.

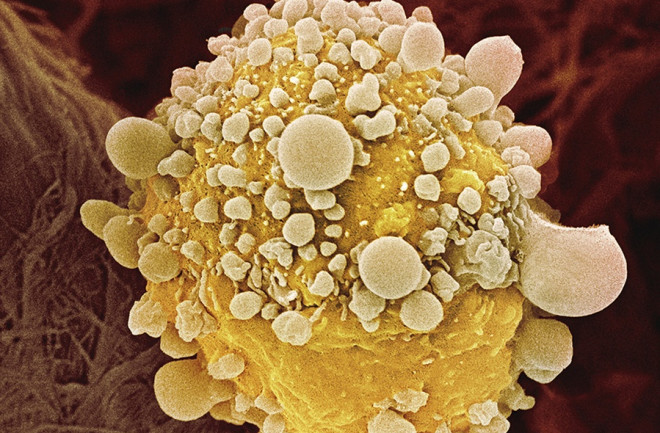

However, as a 95 percent mortality rate suggests, chemotherapy isn’t a viable treatment over the long term. Why is it that pancreatic cancer seems to be maddeningly resistant to most chemotherapy regimens? Pancreatic cancers are often desmoplastic, meaning that they contain and are surrounded by dense scar tissue called fibrosis. This scar tissue can serve as a protective barrier for pancreatic cancers, allowing tumors to resist chemotherapy and evade the body’s own immune system.

Pancreatic cancer cells can also protect their nuclei, home to the chromosomes that contain DNA, by blocking chemotherapy agents. Moreover, in some cases, pancreatic cancer cells can even repair damage to their DNA caused by the chemotherapy drugs that do get into the tumor, further protecting themselves.

Immune System Advantage

Despite all of this bad news, researchers are aggressively looking for new avenues to treat pancreatic cancer. One of the more interesting of these is immunotherapy. Immunotherapy treatments use the body’s own immune system to seek out and destroy cancer cells. If there were a way to strengthen the body’s immune system to give it an advantage, this would offer patients a chance to not only kill cells in the primary tumor, but also allow the body to “scrub” away cancer cells that have spread to other organs.

Immunotherapy takes several forms. The most appealing version would be a so-called cancer vaccine. A pancreatic cancer vaccine could be made of whole pancreatic cancer cells, treated so they can’t replicate, but modified to present certain molecules on the surface of those cells. Those molecules would help “teach” the body’s immune system to recognize and attack these cancer cells. In this way, the patient’s newly educated immune system would then target and kill any future cells that show the same antigens — the real pancreatic cancer cells.

A similar idea involves injecting cancer patients with strains of different bacteria that have been genetically modified to present antigens found on pancreatic cancer cells. This helps teach the immune system to target the rogue cells.

These vaccines have been used in combination with chemotherapy to provide a one-two punch to pancreatic cancer cells. One study used a pancreatic cancer vaccine with modified pancreatic cancer cells known as GVAX, alongside the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide and a special bacterium that boosts the immune response. Researchers reported that those with metastatic pancreatic cancer who received the combination treatment had an overall improved survival with only limited side effects. The added survival translated into several months of extra life, and while that may not sound like much, a few months of additional survival with an aggressive cancer is a big deal.

Beyond the Vaccine

Other possible ways to attack pancreatic cancer cells focus on taking away their ability to hide from the immune system. One approach is to give patients specific antibodies that target the homing devices (essentially chemical receptors) in white blood cells, rendering the tumor cells immunologically visible.

Antibodies like this have been helpful in a variety of cancers, and have potential for pancreatic cancer, but so far they haven’t worked for unclear reasons.

Conversely, the immune system contains triggers to blunt immune responses, and antibodies that block these “off-switch” checkpoints might be able to further reduce the ability of these cancers to escape the immune system. Drugs that work in this manner have been approved to treat melanoma but have been tested in a limited manner, with little success so far, in patients with pancreatic cancer.

In yet another approach, researchers could modify specific white blood cells (called T-cells) to see and target pancreatic cancer cells, although this therapy could attack healthy cells, too. Novel methods to turn these modified T-cells off after a certain time are one way around this potential complication. These approaches could ideally be used alone or in combination with each other or chemotherapy to attempt to “hit” these tumors with everything we have.

Immunotherapy as a science is still young; our understanding of the immune system and how it helps fight cancer is a work in progress. Medical researchers are working hard to develop effective vaccines and other immunotherapy treatments for pancreatic cancer. While it would be fantastic for patients if we could use immunotherapy to cure this disease, just stopping — or even slowing — its progress would be a tremendous leap forward.

Douglas G. Adler is a gastroenterologist and professor at the University of Utah School of Medicine. This article originally appeared in print as "A Master of Evasion."