What's the News: A modified antibody can make its way into the brain and target the development of Alzheimer's-inducing plaques, researchers reported today in two animal studies in Science Translational Medicine. The blood-brain barrier usually keeps drugs and other compounds from entering the brain in large enough quantities to be effective, but these studies show a way to trick the body's own defenses into letting the drug in, demonstrating that this obstacle to treating Alzheimer's could potentially be overcome. How the Heck:

Antibodies---immune proteins that attack disease-causers like viruses and bacteria---are far too big to fit through the blood-brain barrier under normal circumstances. But because of the brain's need for iron, one protein is routinely ferried across the barrier: transferrin, which binds to iron in the blood.

So, the researchers added a molecular structure to the antibody that essentially fooled receptors in the blood-brain barrier into treating the antibody as though it were transferrin, picking it up from the bloodstream and releasing it on the other side, into the brain. Ten times as much of the modified antibody made it past the barrier, compared to a version of the antibody without the add-on.

The researchers tailored the antibody to bind to BACE1, an enzyme that contributes to the formation of Alzheimer's-triggering plaques. The antibody successfully bound to BACE1, interfering with the formation of the plaques.

The antibody reduced amyloid-beta levels in the brain by about 20% in some animal types and about 50% in others, the researchers found.

What's the Context:

Amyloid-beta plaques are thought "to precede and somehow trigger the neurodegeneration and loss of synapses that causes Alzheimer's," wrote neurologist and Alzheimer's expert Steven Paul in a commentary published alongside the studies. Drugs that inhibit BACE1, then, should stop or slow progression of the disease by disrupting formation of these plaques.

Three years ago, tests of an Alzheimer's vaccine found that it successfully removed the plaques after they'd formed but did not lessen patients' dementia. This was likely because the plaques had already done their damage by sparking neurodegeneration; removing them after the fact didn't reverse their effects.

There is no known cure for Alzheimer's disease, and even slowing its progression has proven difficult. Current treatments largely focus on managing symptoms.

If it proves successful, this new approach could also be used to treat other neurological disorders with tailored antibodies.

Not So Fast:

As with the earlier vaccine, this treatment wouldn't help people whose disease is already advanced, since removing the plaques after they've formed is unlikely to show much benefit.

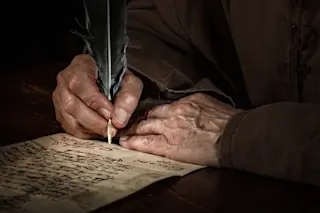

Much remains to be seen before this approach is ready for the clinic. Researchers must develop a human version of the antibody (our transferrin receptors are different from mice's).

Since the treatment would be most beneficial early on, before many plaques has developed, patients would have to take the drug for a long time, meaning its long-term safety must be rigorously tested.

References:

Jasvinder K. Atwal et al. "A Therapeutic Antibody Targeting BACE1 Inhibits Amyloid-ß Production in Vivo." Science Translational Medicine, May 25, 2011. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002254

Y. Joy Yu et al. "Boosting Brain Uptake of a Therapeutic Antibody by Reducing Its Affinity for a Transcytosis Target." Science Translational Medicine, May 25, 2011. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002230

Image: PET scan of the brain of an Alzheimer's patient / National Institute on Aging