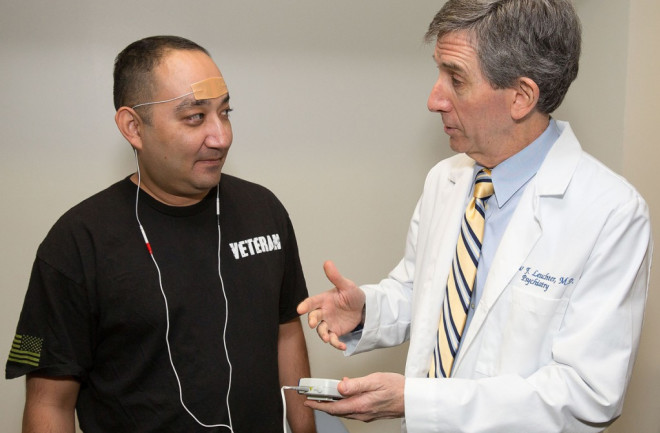

Ron Ramirez, a retired Army sergeant is participating in the second phase study investigating the effectiveness of external trigeminal nerve stimulation for veterans with PTSD. Andrew Leuchter is conducting the research as at UCLA's Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior. (Credit: Reed Hutchinson/CalFoto/UCLA) Millions of people are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) right now. Among military personnel who've been deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, an estimated 31 percent are PTSD sufferers. An estimated 52 percent of people with PTSD also suffer from major depressive disorder (MDD). The cost of treating these disorders is estimated to run as high as $40 billion per year. The social consequences are harder to quantify, but many PTSD and MDD sufferers report marital problems, difficulties bonding with family and friends, and chronic suicidal thoughts. But a team of researchers led by Andrew Leuchter, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at UCLA, believes it has found a new treatment for PTSD and MDD. It’s not a new drug or a new form of psychotherapy. It’s a form of electronic nerve stimulation.

The Price of PTSD

Doctors prescribe a variety of treatments for PTSD and MDD: talk therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), prescription drugs, like serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and sometimes even stronger drugs like opiates. Despite all these interventions, clinical reviews have found that fewer than half of PTSD and MDD patients report any meaningful improvement as a result of treatments like these. “Many symptoms of PTSD are tremendously difficult to treat, especially when a patient is also suffering from MDD,” explains Charles Nemeroff, chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine. But that's exactly what Leuchter and his team set out to do. The team had seen promising research on a new form of therapy known as external trigeminal nerve stimulation (eTNS). In eTNS, non-invasive electrodes deliver small electrical currents that stimulate the trigeminal nerve – the largest and most complex of the cranial nerves. This nerve projects to brain structures that relay signals to a variety of areas involved in PTSD and MDD, including the amygdala and limbic forebrain. “TNS seemed to work well for patients with epilepsy, who often have high rates of depression and anxiety,” says Leuchter. Was it possible, Leuchter and his team wondered, that eTNS could also help with PTSD and MDD? They designed a study of their own to find out. They published their findings in the journal Neuromodulation.

Nightly Stimulation

The team began by gathering a group of adult volunteers aged 18 to 75, who were already taking medication for PTSD and MDD. Leucther’s team assessed these patients even more strictly using a structured interview known as the MINI, which enabled them to choose volunteers who exhibited the most severe symptoms of PTSD on a test called the PTSD Patient Checklist (PCL), as well as the most severe symptoms of MDD on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17).

Every night, the volunteers, like Ramirez, placed electrodes on their foreheads over the trigeminal nerve for eight hours. (Credit: Reed Hutchinson/CalFoto/UCLA) From that group, the researchers selected a smaller group of volunteers who’d already been on a stable dose of medication for at least six weeks, and who didn’t have symptoms of any other mental illness. This gave them a final sample group of 12 volunteers — eight women and four men. Once the researchers narrowed down their group of volunteers, they gave each of the subjects a portable electronic trigeminal nerve stimulation (eTNS) device, which was battery-powered and small enough to carry in a pocket. Every night, the volunteers placed electrodes on their foreheads over the trigeminal nerve for eight hours in conjunction with their medication. The device delivered sequences of electrical pulses to stimulate the nerve, and the treatment was repeated nightly for eight weeks. The results were striking: After four weeks, the subjects’ scores on the PTSD and the HDRS-17 declined by an average of nearly one third. By week eight, their scores were cut roughly in half in both assessments. This meant that eTNS yielded a significant, measurable improvement in each patient’s chronic symptoms of MDD and PTSD, within just two months. “TNS seemed to give very good relief for these patients,” says Leuchter, “particularly for symptoms that are difficult to treat, like startle response.”

A Hope for Help

While the researchers don’t advocate TNS as a primary or solitary treatment for PTSD or MDD, these results do seem to indicate that it could be an effective treatment — along with medication. With the help of treatments like cognitive-behavioral therapy, exposure therapy, talk therapy and antidepressant drugs, TNS could bring significant improvement even for patients who’ve lost hope of a cure. “From a theoretical point of view, these results could have huge significance for PTSD patients,” says Nemeroff. “But this was an open study — the patients were given treatment for eight weeks, but that wasn’t a complete course of treatment. It was uncontrolled — every patient got the treatment; there was no control group. And it wasn’t blind — every patient knew they were getting the treatment. This was also an extremely small sample group — only 12 patients. Psychiatry is a graveyard of seemingly successful studies like this, which didn’t hold up under closer scrutiny.” Leuchter and his team are aware of those issues, and aim to address most of them in more tightly controlled clinical trials on a larger sample group. “We’ve been doing a larger trial for about a year now,” says Leuchter. “We’re augmenting the treatment of 74 military veterans in the Los Angeles V.A. hospital system.” If these larger, more rigorous trials can establish that TNS brings statistically significant improvement to large numbers of patients, they may be able to get the treatment introduced as a standard measure for people who suffer from PTSD and MDD, and, perhaps, bring relief to the millions of people who continue to suffer from these disorders.