Chicago winters are never kind, but for Connie Aguinaldo, a 42- year-old Filipino immigrant, this past winter was especially bitter. Her troubles began when she missed her period. It wasn’t menopause, however, but an unplanned pregnancy. She and her husband had one son, and they had thought about having another child. She accepted God’s gift with gratitude.

But four months into the pregnancy, the bleeding started, and her dreams of maternity became a nightmare. Mrs. Aguinaldo, who worked as an aide in the home of an elderly man, had no insurance. Nonetheless, she had lived in Chicago long enough to know the ropes, so she came to my hospital- -the only one in the city that accepted uninsured patients.

When a patient is miscarrying and is bleeding heavily, the hospital staff performs an ultrasound to check on how far fetal development has progressed. But no developing baby showed up on Mrs. Aguinaldo’s ultrasound. Stunned, she signed all the admitting forms and let the residents go ahead with what they said had to be done. After all, the blood pooling on the gurney where she lay made it clear that something was very wrong.

The staff performed a procedure that dilated her cervix enough to permit the gynecologist to remove the abnormal tissue growing in her uterus. When the procedure was over, the gynecologist explained what had happened, but Mrs. Aguinaldo was too shocked to comprehend how it could be that the child she had treasured for four months had never existed. All she remembered was the disorienting rush of anesthetic, the cramping of her emptied uterus, and the narcotics she received to dull the pain and grief and loneliness. A week later she was sent to me--a gynecologic oncologist-- for follow-up. I had to help her make sense of what had happened to her.

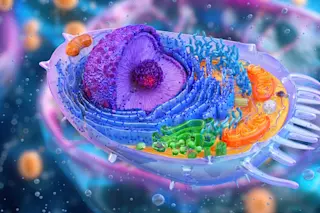

That would not be easy. What Mrs. Aguinaldo had experienced was a molar pregnancy--a gestation that usually produces only placental tissue and no fetus. Like miscarriages and Down syndrome babies, molar pregnancies are far more common among older women, probably because aging eggs are--for unknown reasons--more prone to genetic errors. And the genetic mistake that precedes a molar pregnancy is indeed catastrophic: either before or after fertilization, the egg loses its nucleus and all the maternal genes it contains.

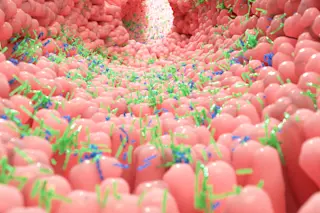

No one knows how often this happens. What we do know is that every now and then--often enough to account for about one pregnancy in every thousand in the United States--a fertilized egg carrying only paternal chromosomes survives. What usually happens is that the genes carried by the sperm somehow duplicate within the egg. By replacing the egg’s missing chromosomes, the sperm provides the number of chromosomes that embryonic development normally requires. One might expect that after such compensation a normal pregnancy would follow. But despite the normal number of chromosomes, no fetus forms.

I explained to Mrs. Aguinaldo how this proliferating tissue masquerades as pregnancy. I told her that the placental tissue grows until the uterus can no longer maintain it. Then--between the fourth and sixth month of pregnancy--the blood vessels in the placental tissue break down and bleeding begins.

Mrs. Aguinaldo sat in my office and listened to all that I said. I don’t know if she ever understood. I wasn’t surprised. Managing molar pregnancies and their complications is a part of my specialty, but these pregnancies are still somewhat mysterious even to me. The danger of molar pregnancies, however, has long been known. In the days before gynecologists could rapidly remove the abnormal uterine tissue, women with molar pregnancies often bled to death.

Today molar pregnancies can be treated with relative ease and safety, thanks to the development of equipment that allows obstetric gynecologists to dilate the cervix and suction out the spongy tissue before the bleeding becomes too severe. But it is the nature of a placenta to invade the uterus’s blood supply, and even for a doctor used to childbirth and bleeding, the torrent that results when the evacuation procedure begins can be terrifying. Moreover, as the tissue is being removed, fragments of the invading placental cells can enter the woman’s uterine veins, get pumped into the heart and out into the lungs, clogging the lungs and blocking oxygen flow. Fortunately, Mrs. Aguinaldo hadn’t experienced any of these problems during the procedure.

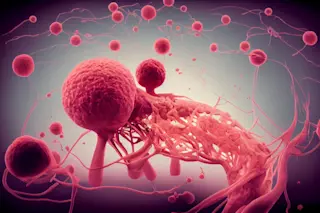

Still, she faced the threat of cancer. In about one case in five, a molar pregnancy turns into a trophoblastic malignancy. In these instances, cells from the trophoblast--the cells that burrow into the mother’s uterus and, in a normal pregnancy, allow the embryo to implant-- grow into the muscle or, in some cases, become transformed into cancerous cells that invade the bloodstream and spread to the liver and brain, to vaginal tissues and bone. Without treatment, women can die from the invasive growth of these fatally transformed cells.

Molar pregnancy doesn’t strike only older women; for reasons no one understands, it is also more common among pregnant teens. But abstract descriptions of cancer and reasoned explanations of genetics don’t go far with girls from Chicago’s South Side, girls whose minds are preoccupied by the more immediate realities of poverty, boys, babies, gangs, drugs--and sometimes church, school, and hope. Too often, they don’t come back for monitoring. Most are lucky. As for the rest, well, I haven’t treated an unlucky one yet, but I haven’t been in the business long. During my training, however, I saw young women die needlessly. They thought they had better things to do than get their blood drawn every week; meanwhile their malignancy grew out of control.

Unlike my young patients, who are so reluctant to cope with their disease, Mrs. Aguinaldo seemed mature enough to understand the threat she faced. So instead of focusing on the dangers of ignoring her condition, we talked about how to stave off any malignant growth. Trophoblastic cancer was once invariably fatal; nowadays, with proper treatment, it is almost always curable. That’s because of two medical improvements developed more than 25 years ago. The first is chemotherapy. The second is a test for human chorionic gonadotropin (hcg), a hormone that placentas produce. Trophoblastic cells secrete hcg, and by measuring levels of hcg in the blood, doctors can monitor the course of disease.

After the abnormal tissue in a molar pregnancy is removed, the level of hcg goes down. But if some cells remain in the uterus or have escaped into the bloodstream, the hcg level resumes its rise. By checking the level each week and starting chemotherapy if it begins to climb, doctors can catch the cancer before the tiny tumors grow big enough to be seen by ultrasound, X-ray, or physical exam. At this time, before the cancerous cells have multiplied enough to develop resistance to chemotherapy, the cancer is much more easily eliminated.

Physicians know a lot, and yet we know so little. Why some women develop trophoblastic malignancy after molar pregnancy while others do not remains a mystery. The amount of tissue seems to have something to do with it: women whose molar pregnancies are diagnosed when their wombs are hugely distended are at high risk, and so are women with high hcg levels. Mrs. Aguinaldo was clearly at high risk. When I began monitoring her hcg level in mid-November, it exceeded 200,000--the highest number on the scale I used.

Over the next two weeks, her hcg level dropped, first to 88,000, then down to 10,000. But then, in mid-December, it shot up above 15,000. That meant cancerous cells had taken hold. When I told Mrs. Aguinaldo, she didn’t cry. She just looked down at her hands. When she looked up, her eyes were full of trust. I had told her we could cure the malignancy if we caught it early. She expected me to keep my promise. She had no questions, only a shrug. Whatever you say, Doctor.

There are two ways to treat trophoblastic malignancy. One method is outpatient chemotherapy: injections of single drugs given in the clinic once every week or two. The other is intensive chemotherapy: toxic infusions of many drugs that waste the patient as they eradicate the disease. The former is for disease that has been caught very early, the latter for women with a worse prognosis. Since blood tests alone can’t tell how far a disease has progressed, I ordered a ct scan for Mrs. Aguinaldo to see if the cancer had spread to other organs and formed new growths called metastases. That would help us decide how much chemotherapy she would need. For most of an hour Mrs. Aguinaldo lay still and silent inside the ct scanner, with nothing to think about but the future and the past, nothing to listen to but the whirring air conditioners, no one to see her but the tech behind the leaded-glass window, nothing to do but wait.

I was anxious, too. Trophoblastic malignancy can be a viciously virulent disease. The cancerous cells often show up first in the lungs--the first stop after being pumped through the heart. Once there, they can obstruct breathing, causing death from asphyxiation. If the malignancy invades the brain, the growing tumor can force the brain down through the base of the cranium, pushing the patient into a coma, then into the morgue. If tumors grow in the liver, the organ fails, causing delirium, then death. To ward off death, chemotherapy has to start immediately, and at Cook County Hospital, like most public hospitals, immediately is hard to come by.

But Mrs. Aguinaldo was lucky. No metastases turned up on the ct scan. The radiologist saw just a little haziness in the uterus, nothing more. Yet the cancer there was growing. The rising hcg level, checked twice, proved that. Because we had enough time to plot a careful offense, Mrs. Aguinaldo would get outpatient therapy. We began a course of weekly meetings. Each Wednesday, I drew blood for an hcg test, waited for the results to assure us that her hcg was still falling, then gave her a chemotherapy shot and a slip scheduling the next week’s appointment.

In principle, the process was simple. But no one had been treated for trophoblastic malignancy at Cook County Hospital in recent memory. Getting the hcg test done on the same morning as the chemotherapy injection meant that a resident had to deliver the blood specimen to the er lab by hand--no telling when it might arrive if we relied on the hospital messengers, who sometimes left specimens in hallways while they crossed the street to get coffee. And we had to lie about the purpose of the test, because by hospital policy, rapid hcg testing was limited to cases of suspected ectopic pregnancy, when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus--say, in a fallopian tube. Apparently whoever had devised the policy had never heard of trophoblastic cancer.

Then, too, Mrs. Aguinaldo had trouble getting to the hospital on time. Her employer didn’t understand her illness. She looked so well, after all, not in the least like a cancer patient. And she had her son to pack off to school; six-year-olds are hard to hurry. After three treatments, her car broke down, so she had to rely on the Chicago transit system and rides from friends. Every week, just when I had given up, she would arrive, full of apologies, the same trusting smile on her broad face.

It took weeks for the chemotherapy to bring the hcg level down, far longer than it should have. During those weeks I was bracing for the rise that would signal resistance to the chemotherapy, a resistance that can be fatal. Twice the graph of her hcg levels plateaued for a week, and I sat with Mrs. Aguinaldo and talked about the possibility of a hysterectomy. I hoped she’d agree to one, for the cure comes faster when the uterus--the source of the transformed cells--is gone. But I also told her the statistics published on her disease: even without hysterectomy, virtually all women at her stage of disease who are treated at national centers are cured. What I didn’t tell her was that she wasn’t at a national center and that I wasn’t sure I could match those odds. It was bad enough that I had to worry about such things.

Twice Mrs. Aguinaldo arrived on a Wednesday morning with her bags packed, ready for surgery, but each time, her hcg level had fallen, the plunging line on the graph granting her a reprieve from sterility and menopause.

In the end, it wasn’t the cancer that caused her trouble. It was the toxicity of the chemotherapy. After two months of weekly injections, Mrs. Aguinaldo’s liver developed a chemical hepatitis, an inflammatory response to processing toxic chemicals. The following week her mouth broke out in sores so raw she couldn’t eat, couldn’t talk--couldn’t even smile-- without pain. And when spring came to Chicago one weekend, she spent a day in the sun, among daffodils and tulips, not knowing that the chemotherapy had the side effect of making her skin sensitive to light. When we met the following Wednesday, her face, hands, and legs--already sallow from the chemotherapy--were mottled with chocolate brown splotches.

We switched to another drug, one that spared her liver but not her thick black hair. One morning she arrived wearing a wig of dull synthetic fiber. She looked pitiful in the padded chemo chair, and in her eyes, behind the steady glow of hope and trust and faith she’d always had, I saw the first shadow of doubt.

Still, she held on. She had reason to be brave. That day her hcg level hit zero, but I gave her a last shot--insurance against any undetected cancer cells that remained. We saw her weekly in the clinic for a while, then monthly. Now her malignancy is gone, and her hair has grown back. Better still, her smile has returned. With the bitter winter past, Mrs. Aguinaldo tells me that she is dreaming--despite her age and experience--of another child. She is hoping for a pregnancy that might redeem the memory of the one that almost killed her.