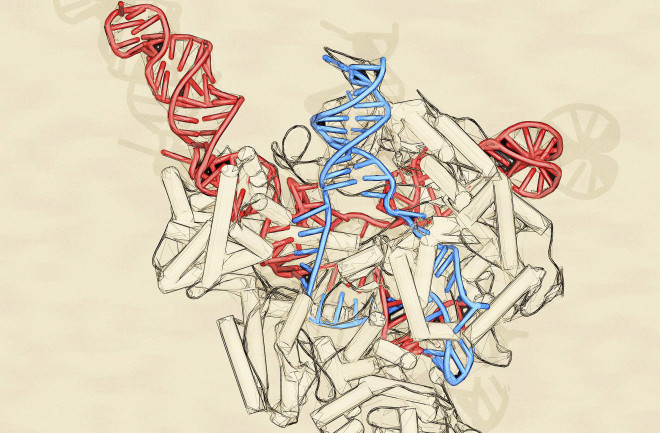

The genome-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 is revolutionizing the field of medicine. The technology, which took off in popularity among researchers about five years ago, can precisely edit DNA. The system includes two components: a DNA-cutting enzyme, called Cas9, and a piece of RNA, called guide RNA. A bit of guide RNA targets a specific chunk of DNA, directing Cas9 exactly where in the genome to snip. But slicing and dicing DNA isn’t without risks. Some researchers have been wary from the get-go, perhaps rightly so as details emerge about CRISPR’s sometimes-troubling safety record.

CRISPR’s Roller Coaster Safety Ride

The pro-CRISPR camp scored a win in March, when Nature Methods retracted a 2017 paper that had stirred controversy. The researchers originally said their CRISPR-edited mice had large numbers of so-called off-target mutations that resulted from Cas9 cutting at places other than the intended location. But the journal pulled the study because the authors couldn’t show if the changes came from gene editing or if they were pre-existing natural variations.

Over the summer, however, a series of papers looking at other aspects of CRISPR raised the specter of cancer. In June, two Nature Medicine studies reported a disturbing tendency. The gene editor was more difficult to use in healthy cells than in cells that lacked a key tumor-suppressing protein called p53. The findings suggest CRISPR might select for tumor-prone cells. “If you put this back into a patient, there’s a certain risk that these cells that have a p53 deficiency might cause cancer in the long term,” says Bernhard Schmierer, a researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, and a senior author of one of the studies.

And in July, U.K. geneticists reported in Nature Biotechnology that CRISPR sometimes removed, flipped or swapped surprisingly large chunks of DNA at on-target sites. These large-scale rearrangements could be an issue if they involve one of hundreds of potential cancer-causing genes.

The new findings highlight possible problems not just when CRISPR misses its mark, but also when it hits its target.

Gaétan Burgio, a geneticist at Australian National University who was not involved in the aforementioned studies, is confident that researchers can overcome the problem, just as he’s confident there will be more findings like these to come. “There are a lot of things we don’t know about the CRISPR system,” he says. “So I would expect more of this in the future.”

CRISPR’s New Target

The CRISPR field has mainly focused on editing DNA, but many diseases could be treated by altering RNA, the molecule that carries out DNA’s instructions. Unlike DNA edits, RNA changes aren’t permanent, so targeting the messenger molecule might mean fewer safety risks.

In March in the journal Cell, researchers at the Salk Institute unveiled a new CRISPR enzyme that does just that. Researchers conducted their initial tests in cells from patients with a particular type of dementia where proteins called tau build up to unhealthy levels; the new CRISPR system successfully rebalanced tau levels.

Its name, CasRx, hints at its future in medicine, according to lead investigator Patrick Hsu. “It’s absolutely inspired by our vision of its therapeutic potential,” he says.

Mammalian Gene Drive Stuck in First Gear

So-called gene drives, which use genetic engineering to preferentially pass on specific genes to offspring, can doom a species. Some controversial proposals have called for using them on mosquitoes to eliminate malaria, or to rid islands of invasive rodents. While CRISPR-based gene drives have shown promise in insects, no one had deployed one in mammals — until now.

In July, researchers announced the milestone in mice, although the results scuttled optimism for a quick pest-control solution. To prove how this might work one day, a team at the University of California, San Diego, attempted to spread a mutation that would turn the rodents white. But only females copied over the change, and sometimes with errors.

“It is much easier in mosquitoes and flies,” says Australian National University’s Gaétan Burgio, who was not involved with the research. Ultimately, he says, given technical hurdles and biological differences specific to mammals, he’s skeptical a gene drive will work on them in the wild anytime soon.

It’s All Relative

In non-CRISPR news, computational biologists have created the largest family tree ever, packed with a whopping 13 million people — including Kevin Bacon — over five centuries. Reporting in March in Science, researchers used public genealogy profiles to assemble the massive pedigree. They found longevity is probably less genetically determined than previously thought. But the tree’s real utility may be yet to come. Adding genetic and health information could reveal much more about what causes certain diseases.

Protein Therapy Goes in Utero

For the first time, doctors used a drug to treat a genetic disease before birth. People with XLHED can overheat because they lack a protein critical for sweat gland development. In an April study, doctors in Germany, Switzerland and the U.S. described flagging three fetuses as having the inherited disorder. By injecting the missing protein into the amniotic sac at the right time in the fetuses’ development, the doctors restored the trio’s ability to sweat. Researchers say the technique could be adapted for other conditions, such as some forms of facial clefts.