On the uncharacteristically cool morning of July 22, 2009, 24 scientists gathered at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. The topic: a troubling new retrovirus called XMRV. A paper in the journal Science was about to implicate the virus as the cause of a devastating disease with a dismissive name: chronic fatigue syndrome, or CFS. Doctors have compared the worst cases of CFS to end-stage AIDS. CFS patients have cancer rates that are significantly elevated and immune systems that are seriously impaired. The disease can confer a kind of early dementia and may shorten its victims’ lives by 20 years.

Scientific explanations for the rise of CFS cases, a phenomenon dating to the mid-1980s, have mostly focused on viruses, but psychiatric theories have abounded, too, driven primarily by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which promoted the idea that CFS was “hysteria” or hypochondria. Many scientists and doctors familiar with the disease had long suspected a retrovirus, an organism rife in nature that invades the immune and central nervous systems, as seen in AIDS. Once a retrovirus has infected an organism, it commandeers that organism’s genetic machinery, turning a once-healthy cell into a retroviral powerhouse that spreads the infection to more cells in an irreversible cascade.

By 2009, scientists had identified a mere handful of specifically human retroviruses: HIV 1 and 2 (human immunodeficiency virus), the cause of AIDS; the HTLV group (human T-cell lymphotrophic virus), at least one of which — HTLV-1 — was a cause of leukemia, lymphoma and an MS-like neurological disease; and HBRV (human beta retrovirus), tentatively considered the cause of a severe liver disease called primary biliary cirrhosis.

At the center of speculation about the new retrovirus that day in July was an immunologist and AIDS researcher named Judy Ann Mikovits (pronounced My-ko-vitz), a diminutive 51-year-old in a sleek black suit and a crisp white shirt. Mikovits was a 20-year veteran of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) who had coauthored more than forty scientific papers. During her final two years at the agency, she had directed the Lab of Antiviral Drug Mechanisms, where she studied therapies for AIDS as well as one of its associated cancers, Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Mikovits had flown to the NIH meeting from Reno where she had been working in a small lab on the campus of the University of Nevada medical school for the previous three years. She listened as other scientists presented what they knew about XMRV, which was largely that it might be linked with prostate cancer.

Three years earlier, investigators had found genetic sequences of the novel retrovirus in prostate tumors from men with that disease. Whether XMRV caused any human diseases — or was even a transmissible, specifically human infection — was uncertain at best.

Last to speak, Mikovits led her audience through a terse, rapid-fire slide presentation. She offered persuasive data suggesting that XMRV was infecting a large majority of those suffering from the myriad neurologic and immunologic abnormalities of CFS, thought to afflict between 1 million and 4 million Americans and perhaps 17 million worldwide. Mikovits had found evidence for retroviral infection in blood and plasma (and would later find evidence in saliva). She also offered proof that patients had mounted an immune response to the virus.

Frank Ruscetti, who had discovered HTLV-1 while working in Robert Gallo’s Laboratory of Tumor Cell Biology at the NCI in 1980, was Mikovits’s primary collaborator. It was Ruscetti who had found the new virus in both T-cells and B-cells of CFS patients. Using a labor-intensive cell culturing technique for hunting retroviruses that he had pioneered in the 1970s, Ruscetti had transmitted the pathogen from patients’ T-cells to uninfected T-cells in the laboratory.

The implications were hardly lost on the Bethesda crowd: If the virus was transmitted in cell cultures in Ruscetti’s lab, it could also be contaminating the nation’s blood supply as a result of blood donations from unknowingly infected donors. As if to confirm those fears, Mikovits reported evidence for XMRV in 3.75 percent of a group of 218 people serving as healthy controls, selected randomly by zip code. Extrapolated to the general population, that meant the recently discovered retrovirus might already have infected at least 10 million still-healthy Americans, each of them innocent of their acquisition of the pathogen.

Probably the most surprising aspect of what Mikovits said that day, however, had to do with the fact that the new virus appeared to be in the murine leukemia family, which belonged to the larger retrovirus genus known as gammaretroviruses. The latter infect vertebrates ranging from gibbon apes to koala bears to reptiles to domestic cats and are known to cause leukemia, as well as neurological disease.

Murine leukemia viruses, or MLVs, are carried in the genomes of mice (murine comes from the Latin for “mouse”). MLVs so dependably cause cancer in lab-bred mice — especially leukemia and lymphoma — that a small fraternity of scientists at the NCI and elsewhere has fruitfully studied these viruses since the 1960s in an effort to understand how human cancer begins.

Given such far-reaching implications, it was not surprising that when Mikovits stopped talking, nearly a minute passed before someone spoke, and then it was to say, “Oh my God.”

That simple expression of dread was the preliminary gasp in what would become, in the three years that followed, the most clamorous scramble in recent medical history to prove or disprove what seemed to be a viable hypothesis, one so dire it was facetiously dubbed the Doomsday Scenario by one skeptic.

Indeed, the controversy over Mikovits’s findings didn’t even have a chance to smolder; it erupted like a wildfire on several continents. The contentious debate reached an apex in the spring of 2010, when one group of government scientists at the FDA found evidence to support Mikovits’s CFS discovery, and another group at the CDC seemed to discredit her findings by failing to reproduce them.

At stake was the resolution of a potentially infectious disease afflicting millions worldwide — or, in the naysayers’ view, the timely dismissal of a wrongheaded avenue of investigation.

In the end, the NIH’s AIDS czar, Anthony Fauci, asked his friend Ian Lipkin, a neurologist and virus hunter at the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, to settle the impasse. Last September Lipkin announced the results of his analysis at a tightly controlled press conference: XMRV was not actually a human pathogen, he said, confirming an earlier report, but a man-made contaminant unwittingly manufactured in a lab in the 1990s.

After novelistic plot twists that included a police raid, an arrest, and a public tarring and feathering of the outspoken Mikovits, the scientific community is now convinced that XMRV was a false lead. Yet the expenditure of time and money to reach that conclusion was hardly an exercise in futility.

The 2009 meeting in Bethesda marked the beginning of a change in the CFS cosmos, with a slew of prestigious scientists entering the field and government officials taking a more serious view of this formerly neglected disease. Moreover, the XMRV saga opened a rare window into the way scientists and government officials respond to findings that not only challenge the status quo but have profound implications for public health.

JUDY MIKOVITS HAD BEEN SO COCOONED IN the world of AIDS that she had never heard of chronic fatigue syndrome until 2006, when she was hired to consult for a Santa Barbara–based foundation supporting investigation into human herpes virus six (HHV6), which had been implicated in the disease. At the time, she was newly married and living in California, working on cancer therapies for a small drug-development firm. Mikovits attended the HHV6 Foundation’s annual spring scientific conference, held that year in Barcelona.

One of the presenters was Daniel Peterson, an internal medicine specialist and an internationally known clinical expert in CFS from Nevada, where a well-publicized outbreak of the disease had occurred in communities near Lake Tahoe in 1984 and 1985. Mikovits listened, fascinated, as Peterson described a group of 300 CFS patients in his practice who suffered from white matter brain lesions, a host of immune system abnormalities, and myriad chronic viral infections including HHV6.

More interesting to Mikovits, however, was Peterson’s report that 5 percent of this group had developed rare immune system cancers during their illness. In all, 77 of the 300 had lymphoma, leukemia, or cellular changes that were predictive of those diseases. Mikovits believed that the signature of the immune system deficiencies described by Peterson, in combination with his report of lymphomas, was strongly reminiscent of the immune dysfunction, opportunistic infections, and cancers of AIDS.

The hypothesis was so dire that one skeptic facetiously dubbed it the Doomsday Scenario.

Also in the audience in Barcelona that day was Annette Whittemore, a rich, politically well-connected Nevada native. Her adult daughter had suffered from CFS since childhood and had been under Peterson’s care for many years. Whittemore and her husband, Harvey — a Reno attorney, real estate magnate, and former lobbyist whom local reporters called “the most powerful man in Nevada” — had been holding fund-raisers at their summer vacation mansion overlooking Lake Tahoe for some years to support research into their daughter’s illness.

They also had been lobbying the state legislature and U.S. Senator Harry Reid, a longtime friend, for government money to fund an institution at the University of Nevada in Reno dedicated to the study of CFS. In 2005 the state legislature approved a bill committing $12 million to get the $77 million construction project off the ground. (A variety of other sources, including the Whittemores themselves, would fund the rest.)

Plans were laid for a steel and glass-clad building on the UNR campus that would house, four years hence, the Whittemore Peterson Institute: a collection of labs, clinics, and the office of the president, Annette Whittemore.

Whittemore was impressed when Mikovits — first to the microphone to comment when Peterson finished — said, “I’m a cancer researcher. Number one, I look for viruses in cancer, and number two, this smells like a virus.” Whittemore invited Mikovits to Reno for a six-week stay that summer, during which Mikovits developed a bank of CFS patient tissues for further study. The many patients too weak to stand or walk, requiring wheelchairs or scooters or — to keep their balance — canes, made an impression. By summer’s end she had accepted an offer to become research director of the institute.

ONE OF THE FIRST THINGS MIKOVITS DID was to employ a microarray — a small tray seeded with DNA from nearly every known virus — to flag viral DNA in human white blood cells. When Mikovits used the microarray to study CFS patients, she “saw all these infections — lots of chronic, active infections — cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpes six,” she says. It looked like an acquired immune deficiency syndrome, “like an AIDS patient,” with a weakened immune system enabling opportunistic infections to take root. The question was, why did they have chronic immune dysfunction?

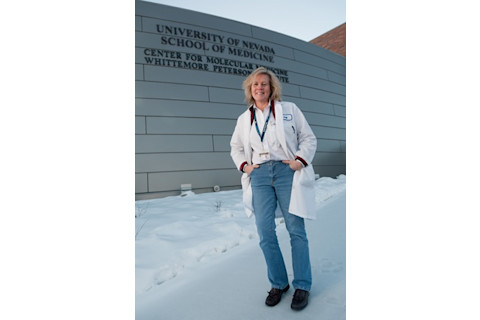

Judy Mikovits stands outside her former lab at the Whittemore Peterson Institute in Reno, Nevada, where she tried to prove a retroviral cause of CFS. (Credit: David Calvert/AP Images)

David Calvert/AP Images

Mikovits was keenly aware of two well-documented immune system abnormalities in CFS. One was a stark deficiency in the total number of natural killer cells, which seek out and destroy viruses and cancer cells, and a reduction in the killing power of the natural killer cells that remained.

A second abnormality had to do with elevated levels of RNase L, an enzyme that provides immunological defense against viruses and cancer. “Given that the job of RNase L was to chew up RNA viruses, we hypothesized the possibility of a novel RNA virus in our patients,” Mikovits says. (RNA viruses use ribonucleic acid as their genetic material; examples include SARS, polio, and retroviruses like HIV.)

Patients with aggressive prostate cancer, the second-leading cause of cancer deaths among men, had RNase L abnormalities too. In 2002, Robert Silverman, an RNase L expert at the Cleveland Clinic, discovered that a mutation in the RNase L gene was frequently present in men prone to early onset of the disease.

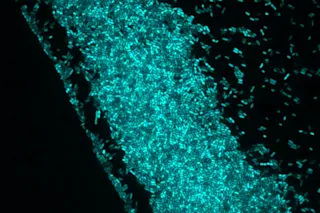

Silverman, too, suspected an RNA virus might be the infectious cause of aggressive cancers in relatively young men. And he had some preliminary evidence: When he added DNA from malignant prostate tissue cells to a microarray, a novel retrovirus emerged. Further analysis showed that the retrovirus was a gammaretrovirus closely linked to MLVs found in mice, though analysis revealed its genome to be slightly — less than 3 percent — different.

Silverman’s group at the Cleveland Clinic and collaborators Joe DeRisi and Don Ganem in San Francisco reported their discovery of a new, apparently human retrovirus in PloS Pathology in March 2006; the researchers added the word xenotropic to the name to indicate that the virus, although carried from generation to generation in the mouse genome, caused disease only in other animals. At the time, the paper attracted little interest from the scientific community.

In January 2009, Mikovits and Ruscetti — by then also hot on the trail of the enigmatic virus — met with Silverman in San Diego, where he had been invited to speak. Over lunch, Mikovits laid out her preliminary data. Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology to greatly amplify what began as tiny amounts of the virus, she had found evidence for the novel pathogen in CFS patients as well. “We all agreed it was worth following up,” Mikovits recalls.

Silverman and Ruscetti signed a confidentiality agreement with the Whittemore Peterson Institute and became Mikovits’s collaborators. Their paper, “Detection of an Infectious Retrovirus, XMRV, in Blood Cells of Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome,” appeared in the online edition of Science on October 8, 2009. Two MLV experts, one from Britain and another from the United States, extolled the importance of the work in an accompanying editorial, writing, “If these figures are borne out in larger studies, it would mean that perhaps 10 million people in the United States and hundreds of millions worldwide are infected.”

By November 2009, Stuart Le Grice, head of an influential NCI division called the Center of Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Cancer Virology and the person who had convened the NIH meeting the previous summer, had 10 HIV scientists working full time on XMRV. “It’s very interesting to be in the middle of a situation like this,” Le Grice commented at the time. “I worked with Hoffmann–La Roche for seven years in Switzerland in the first days of HIV, and the action plan that we put together at Roche is the same plan that we put together here.”

Mikovits, for her part, took pains to tell members of the lay press and other scientists that the virus had not been proved to cause CFS, merely that it was “associated” with the disease. But in private, contemplative moments that fall, the researcher indicated she felt confident that the long-enduring CFS puzzle was likely solved; her real interest going forward was in developing treatment for those who were suffering.

WHILE SCIENTISTS AT THE NCI WERE repurposing laboratory space to study XMRV, William Reeves, the researcher in charge of CFS for 18 years at the CDC (he died last August) and a longtime proponent of the psychiatric explanation for the disease, sounded a sour note, telling The New York Times, “If we validate it, great. My expectation is that we will not.”

For many researchers who had followed the CDC’s desultory history in CFS over the years, Reeves’s comments aroused concern. Twenty years earlier, another scientist, immunologist Elaine DeFreitas of the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, had discovered retroviral gene sequences in CFS sufferers.

The agency failed to replicate her findings after a series of lab mishaps and a wholesale departure from DeFreitas’s protocol for finding the virus. Afterward, the CDC reverted to its years-long claim that CFS was lacking in biological abnormalities and its assertion to doctors that performing any but the most standard tests was a waste of money.

Academic research into the cause of the disease went into a 20-year stall, punctuated in 2006 by a press conference in which Reeves and the CDC’s director at the time, Julie Gerberding, announced what they portrayed as a breakthrough discovery: CFS was caused by a genetic predisposition to difficulty responding to stress.

In late 2009 at CDC headquarters in Atlanta, a virologist in the agency’s retroviral branch, William Switzer, was attempting to replicate the XMRV finding in CFS. In an ironic twist, Switzer was working under the direct supervision of Walid Heneine, the very scientist who had failed to replicate DeFreitas’s work 20 years before. So far, the agency had found XMRV in 2 out of 162 men with prostate cancer but was having zero luck finding it in agency-selected CFS patients.

By the start of 2010, it seemed as if the Science article had launched a cottage industry of researchers on two continents who were unable to find XMRV in CFS patients. The first negative results appeared in January when a group from Imperial College London published an article in PLoS ONE saying they had failed to find the virus in 186 CFS patients using PCR technology.

In February, a Dutch group at Radboud University followed with another negative PCR study, reporting in the British Medical Journal that it had been unable to find XMRV in 32 patients or 43 healthy controls. Back in the United States the following summer, the CDC reported in the journal Retrovirology its inability to find XMRV in either CFS patients or controls.

Despite the skepticism emerging in Europe and the U.S., events were quietly unfolding in a laboratory at the FDA in Rockville, Maryland, that would put Mikovits’s critics back on the defensive.

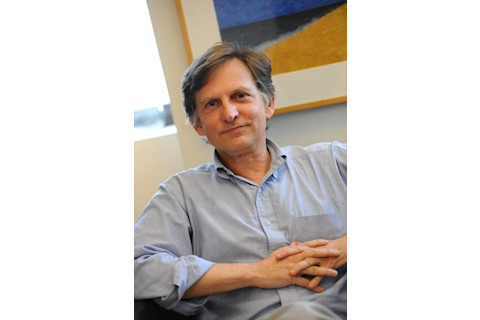

Ian Lipkin of Columbia University orchestrated a grand experiment to learn whether XMRV could be found in patients with CFS. The answer: No. (Credit: Columbia University)

Columbia University

Shyh-Ching Lo, a pathologist and director of the FDA’s Tissue Microbiology Laboratory, discovered that he possessed 37 unopened vials of whole blood and plasma from CFS sufferers, the pristine cryopreserved remains of experiments undertaken in the early 1990s. To his surprise, Lo found four different MLV-related gene sequences in 32 of the 37 patient samples.

Although the gene sequences were not identical to the Mikovits-Ruscetti XMRV gene sequence reported in Science, they were so close Lo believed he had found genetic variants of a single MLV-like virus species that likely included XMRV. Lo was encouraged by the variants because retroviruses are extremely mutable pathogens that change their gene sequences again and again in response to immune system efforts to kill them. “This is what we expect,” Lo said at the time.

Lo asked a friend and sometime collaborator, Harvey Alter, chief of the infectious disease section in the department of transfusion medicine at the NIH, for some healthy blood samples to use as controls. Alter, who had discovered the hepatitis C virus in the 1970s, provided Lo with blood that had been donated to local blood banks by presumably healthy people. Lo found 6.8 percent of the healthy controls positive for MLV-related infection. The startling figure doubled the Sciencepaper’s estimates of prevalence for Americans who might be infected with a doomsday bug. Lo and Alter’s paper was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in August 2010.

Mikovits and her collaborators were over the moon when they learned of Lo’s success at the FDA. Nevertheless, by the fall of 2010, the majority of published papers were broadly negative. Increasingly, the word contamination was bubbling up in scientific articles and blogs to account for both the XMRV and the MLV-like virus findings. Critics postulated that mouse DNA was floating in the air in the laboratories, or lying in wait in the chemical reagents used to find the virus, or sitting at the bottoms of test tubes used to collect blood specimens.

Le Grice’s influential colleague at the NCI, a government consultant named John Coffin, had his own theory: XMRV had been accidentally created in a lab at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland sometime between 1993 and 1996. Coffin described how lab workers there had transplanted human prostate tumor cells into an immune-deficient lab mouse, a common procedure for procuring a colony of cells, or a human cell line, for further study.

When the human cells failed to thrive, lab workers transplanted those same cells into another mouse. Coffin and his collaborator, Vinay Pathak, suggested that with each passage, the human cells acquired genetic portions of a murine leukemia virus, which then merged to form a new virus — a hybrid of the parent sequences.

The successful prostate cell line that resulted from this event, named “22rv1,” was thus infected with a hybrid, lab-created virus: XMRV. The cell line had been sent to labs around the world — including, as luck would have it, Robert Silverman’s lab at the Cleveland Clinic.

Obviously, if XMRV had been inadvertently manufactured as the result of lab experiments in the mid-1990s, it could not be causing disease in CFS or prostate cancer patients who had fallen ill in the 1980s or early 1990s. XMRV was “dead,” Coffin announced in April 2011. He advised CFS researchers to “move on.”

By early summer 2011, Silverman was ready to accept Coffin’s analysis and had become increasingly uneasy about his contributions to the 2009 data in the Science paper about CFS. Two years earlier, by amplifying the virus in tissue samples, Silverman had sequenced XMRV in seven of 11 CFS patient samples sent to him in March of 2009 by Mikovits. But when he reexamined those original samples again in the summer of 2011, Silverman discovered that all seven were contaminated, not with mouse DNA but with an infectious molecular clone originally made in his own lab in 2006.

After researchers began using the Silverman clone for their experiments, it replicated “like crazy” and spread beyond the boundaries of those projects throughout the lab, Silverman now found. The discovery was even more troubling since Silverman had sent his synthetic clone to “about a hundred labs” around the world.

In September, Silverman and the other authors of the Sciencepaper began working with the magazine’s editors on the wording of a partial retraction of the data contributed by Silverman. (Silverman argued for a full retraction.) It was published in the online edition of Science on September 22, 2011, two years after the original study. Bruce Alberts, editor-in-chief of Science, unilaterally retracted the paper in full two months later.

Mikovits nevertheless remained deeply concerned that the prevalence of the Silverman clone in so many laboratories had prevented scientists from looking for greater virus sequence diversity that might have revealed additional MLV-like viruses, as Lo had done at the FDA. No one had yet disproved that a murine leukemia virus was spreading through human population, she insisted—an observation greeted with skepticism and occasional derision by scientists who were following the controversy.

THINGS WERE UNRAVELING BETWEEN ANNETTE Whittemore and Mikovits as well; earlier, on September 29, 2011, Whittemore had fired Mikovits as research director of the Whittemore Peterson Institute. In response to press inquiries, Whittemore offered “insubordination and insolence” as reasons for the dismissal. The dispute had to do with Mikovits’s insistence that another scientist at WPI had improperly ordered a cell line for experiments that were beyond the purview of his authority. Whittemore roundly disagreed with her scientific director.

Three weeks later, Mikovits — who had returned to California to be with her husband — was served with a civil lawsuit by the WPI claiming she had “purloined” lab notebooks and other intellectual property belonging exclusively to the WPI, charges her attorney has vehemently denied.

Finally, in a development that stunned even her harshest detractors, Mikovits was handcuffed in her home by police on December 4 and booked at the Ventura County jail as a “fugitive from [Nevada] justice.” She remained there for five days, classified as a “flight risk,” until her husband was able to obtain legal representation and have her released on bail.

But L’Affaire Mikovits and the search for retroviral infection in CFS has not come to an end. In January 2012, Ian Lipkin invited Mikovits and the NCI’s Ruscetti to contribute to a rare, NIH-funded study to be orchestrated at Columbia. In fact, Lipkin braved the disapproval of his high-level friends at the NIH to insist that Mikovits be included in the study, which had Ruscetti and Mikovits, the CDC, and the FDA testing blood from nearly 150 CFS patients and an equivalent number of controls.

Each of the three government teams was given blood samples from the same patients and controls. Lipkin asked each group to employ the lab methods they had used in their original papers. Lipkin and his staff broke the codes and analyzed the results.

None of the participants — including the NCI team — found evidence of XMRV in any samples. Given the definitive results and objective design of the study, the scientific world at last considers the XMRV case closed.

Mikovits is unqualified in her gratitude to Lipkin for insisting that unbiased science be done. XMRV “is one scary virus in the laboratory,” she says today. “It seems to be ultra-stable and can spread through droplets in the air, like a mycoplasma. How could any of us have known?”

In spite of the disappointing results, Mikovits continues to believe a human retrovirus will be discovered eventually to lie at the heart of CFS. “I still see the footprints of a retrovirus there,” she says. “In the Lipkin study, 3 percent of the controls and 3 percent of the CFS patients had an antibody cross-reactivity to something. It cannot be XMRV, since XMRV doesn’t exist as a human infection. But it’s very close.”

Mikovits was handcuffed in her home by police and booked at the county jail as a ‘fugitive from justice.’ She remained there for five days.

The possibility that Mikovits’s prediction is correct is being explored. A new, $10 million research initiative to investigate CFS was launched in September 2011 at Lipkin’s laboratory after multi-millionaire hedge fund manager Glenn Hutchins, a director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and vice chairman of the Brookings Institute, provided the cash and promised more money in the future should the investigation bear fruit. (Lipkin identified the brain infections Borna virus in 1990 and West Nile virus in 1999.)

“What’s occurred in the last 30 years is criminal,” Mikovits says today. “Mothers and fathers got sick, their children got sick.” But with heightened attention, she adds, patients are likely to get help soon. Even lacking a causal pathogen, biomarkers in this patient population can be studied for clues. “We can find therapies for the CFS patient population even before we determine the exact cause,” Mikovits says. For his part, Lipkin credits Mikovits with “opening Pandora’s box. Right or wrong about this particular virus, she deserves credit for awakening interest in CFS.”

For a disease that has languished in a kind of political never-never land for at least one human generation, leaving millions profoundly disabled, that is significant progress.