“I swear I’ve never had a cough like this,” Dr. Jean McDonald said, catching her breath after a string of wheezy barks. “Would you mind doing a quick consult?”

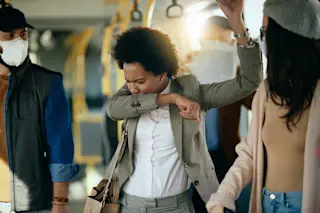

Summer was over, and back-to-school bugs were swirling among hospital workers like leaves in a squall. Still, something about that call bothered me. To pediatricians like Jean, coughs and colds were bread-and-butter medicine. It had to be serious if she asked for help.

“No problem. I can meet you in the clinic in 15 minutes,” I said.

“Um, can we make it a little later, please?” Jean sputtered. “Right now I’m doing rounds with the transplant team.”

“Just make sure you wear a mask around patients,” I joked.

I had hit a nerve. “Girl, I’ve been wearing masks for the last six weeks. See you in an hour,” Jean replied.

The first time I crossed paths with Jean McDonald, I liked her right away. A lively expert in childhood liver disease, she had come to me about getting shots and pills for a monthlong trip to Africa. By the time I’d fixed her up, we were friends.

We never got a chance to talk about the trip. Once back from the bush, she seemed consumed by work. When I saw her in the hallway, she was usually sprinting like a rabbit. One quick wave and off she’d go. But the Jean who showed up in my exam room that day was very different: step slowed, eyes hollow, face drawn.

“I’m running on empty,” she said. “It’s this cough. Even with codeine, it keeps me up half the night.”

Despite her illness, Jean still had a heavy workload, so I got right to the exam. Vital signs: temperature, 98.6 degrees; heart rate, 60; respiratory rate, 12 breaths per minute. I checked her ears, throat, neck glands. Everything was fine there too.

“Let’s move on to your lungs,” I said. “I need to rule out pneumonia.” As I fished for a stethoscope in my pocket, I imagined the moist, snuffling sounds of pneumonia, like bubble wrap filled with fluid and cells. Then, in my mind’s ear, I heard the plaintive melody of asthma. After all, adults with asthma can also present with chronic cough. Then I listened. After rubbing the metal rim of the stethoscope to take away its chill, I moved it around Jean’s back as she slowly inhaled and exhaled. Nope. Her lungs were clear.

“Tell me more about this cough,” I urged, eager for a clue. “What about unusual exposures? Have you had any recent close contact with someone sick, any bird or animal encounters, desert dune buggy rides, overseas travel?”

“Contact with the sick? That’s the story of my life. But nothing exotic, as far as I know.” Jean paused. “As for the cough, at first it was no big deal. But after that-man, oh man-it got so bad I could barely catch my breath. And not just once or twice, but over and over and over.”

Aha! Could it be? I began thinking of a pathogen famous for provoking coughing fits, a disease that once plagued infants. Now in countries with high rates of childhood immunization, it targets young and middle-aged adults. Most would never know what hit them.

“Jean,” I said, “did you ever think you might have whooping cough?”

Whooping cough, better known as pertussis to microbiologists and infectious-diseases specialists, is the cunning work of Bordetella pertussis. Although physically small by bacterial standards, the organism possesses weapons that would put a medieval dungeon master to shame. From filamentous attachment spines to toxins that paralyze and kill cells, the species is well equipped for wreaking havoc in the human respiratory tract. Its hallmark, in fact, is a redundancy of weaponry. After an infection is successfully established, several types of toxins temporarily stun the host’s immune cells, thereby protecting the invading organisms and also prolonging their siege.

Early on, however, the invader causes symptoms remarkably like that of the common cold: runny nose, watery eyes, sore throat, fatigue. It usually takes at least one to two weeks before a pertussis infection has so colonized and injured the airways that it provokes a run of explosive coughs, each lasting more than a minute. Patients gasp for air afterward, hence the legendary “whoop.” Meanwhile, they may carry on with their normal lives, often sharing the infection with unsuspecting schoolmates, friends, and coworkers.

Ironically, by the time the warning sounds, the patient’s immune system has brought the infection under some control. It’s during the early, nonspecific phase of infection that Bordetella pertussis is most contagious, most easily cultured from the nose and throat, and most easily treated, usually with an erythromycin-type antibiotic. By the time a patient develops a paroxysmal cough and finally gets to a doctor, the trail is cold; a culture will typically show no sign of infection, and only specialized tests can prove the recent presence of the culprit. Thus many cases—especially infections of adolescents and adults—are never diagnosed and treated.

But even with antibiotic treatment, the violent coughing fits can last four to six weeks, occasionally causing infants and youngsters to suffer such dramatic consequences as eye, nose, and brain hemorrhages as well as rib fractures and hernias. Infants under 1 year old with pertussis are also prone to seizures, apnea (pauses in breathing), and a temporary decline in mental function called encephalopathy. A final complication in babies is malnutrition-nonstop coughing robs them of time and energy to eat, sometimes resulting in skin-and-bones starvation. Adults like Jean, on the other hand, rarely lose more than a few pounds.

Meanwhile, my friend was surprised—and puzzled—by my diagnosis.

“Pertussis—what an interesting idea! But I was vaccinated in childhood. Shouldn’t I still be immune?”

“Not necessarily. It’s a short-lived vaccine that’s only given in childhood, even today. When we were kids, the final pertussis booster was given around age 7. By the time you entered medical school, your protection was probably gone.”

“Wow. I thought pertussis was ancient history here.”

Jean’s mistaken impression was familiar. Until a year earlier, I had held the same belief. But then I read a research study involving college students on our own campus-the University of California at Los Angeles. The undergraduates had come to the student health service with a persistent cough of six days’ or greater duration. Of 130 subjects evaluated over 30 months, 26 percent had evidence of recent infection with Bordetella pertussis. Whooping cough was alive and well in our own backyard. Just as in Jean’s case, the students’ childhood shots protected them for a decade or two, but certainly not for a lifetime.

Like a good scientist, Jean wanted some evidence. And after six weeks of symptoms, both she and I knew that a culture swab was not likely to produce it. But we had another method. We could look for pertussis antibodies, the same way the students had been diagnosed in the study. A week later, Jean’s blood test returned unequivocally positive. I hadn’t been able to alleviate her suffering, but at least I had given her an answer.

Claire Panosian Dunavan is a tropical and infectious-diseases specialist at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California at Los Angeles. The cases described in Vital Signs are true stories, but the authors have changed some details about the patients to protect their privacy.