This story was originally published in our Nov/Dec 2023 issue as "Blowing Smoke?" Click here to subscribe to read more stories like this one.

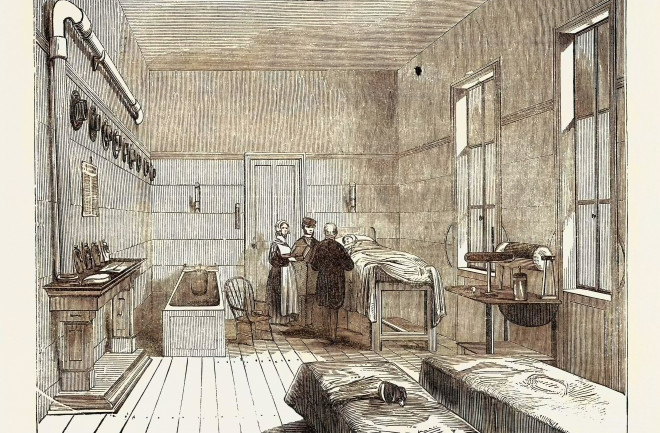

If you were to drown in the Thames River in the late 18th century, your best chance of survival would be for a good Samaritan to pull you from the water and carry you to a receiving house outfitted with basic medical equipment — possibly even located in the pub you had just stumbled out of — established by the local life-saving organization, the Royal Humane Society. There, medical assistants who had been trained for exactly this kind of rescue would begin the work of bringing you back from sudden death.

They would strip you bare, dry you off, and clean your mouth and nostrils. They would warm your body, either by rubbing your skin with wool or heated brandy, or by laying you near a fire. And then one of the assistants would light a tobacco pipe, cover the bowl with his handkerchief, insert the opposite end into your rectum, and blow.

Whether you lived or died would have nothing to do with the tobacco-smoke enema, of course. But at the time, this was one of the most popular therapies for drowning victims, believed to be “amongst the most efficacious applications” — or so writes physician Thomas Cogan in a pamphlet published in 1795 by the Royal Humane Society. (The italics are Cogan’s.)

Tobacco has long been understood to be an irritant, and therefore a stimulant. Cogan, who with William Hawes co-founded London’s Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned (later called the Royal Humane Society) in 1774, justifies the therapy like this: “It is not only the admission of a kindly warmth into the internal parts of the body which in all cases must prove advantageous, but its stimulus connected with its warmth seems admirably adapted to excite irritability and to restore the suspended or languid peristaltic motion of the intestines.”

Various devices were used to administer the enema: a regular tobacco pipe, tubes of different kinds with metal nozzles on each end, and, eventually, a bellows. As far back as the 15th century, physicians believed rectal insufflation had reanimating powers. Instructions from the physician Paulus Bagellardus to midwives in 1472 recommended a similar therapy for stillborn babies: “If she find [the newborn] warm, not black, she should blow into its mouth, if it has no respiration … or into the anus.”

The tobacco-smoke enema was one of several remedies for drowning victims used in Europe at the end of the 1700s. If the enema didn’t reanimate the victim, a rescuer might try shaking the person vigorously, blood-letting, or even applying red-hot irons to the bottom of the feet. Chest compressions, delivering air to the lungs (see sidebar), or applying electric shock to the heart also were recommended alongside rectal fumigation — techniques remarkably close to our modern resuscitation procedures.

These therapies for resuscitating drowned persons were spread by life-saving societies. A response to the high rate of drownings — in the 18th century, it was a leading cause of accidental death in Europe — the first life-saving society was founded in the canal-threaded city of Amsterdam in 1767. Inspired by the success of the Dutch society and a growing humanitarian movement, similar organizations popped up in Paris, Milan, Venice, London, Hamburg and St. Petersburg in the following decade, and in the 1780s, in Philadelphia and Boston. These organizations were often founded by doctors and published research on the latest life-saving techniques. Some even paid monetary rewards, funded by a combination of public and private donations, to the good Samaritans who aided drowning rescues. According to the Royal Humane Society’s 1795 report, 70 percent of the 2,572 rescue attempts made by the society were successful (though what medical state the apparently “drowned” were actually in may have varied).

“What was lacking was not the creativity of devising rescue techniques but the ability to separate effective from ineffective therapies,” writes Mickey Eisenberg, an emergency medicine specialist, in his book, Life in the Balance: Emergency Medicine and the Quest to Reverse Sudden Death.

So, is there any efficacy in that once highly recommended smoke enema? “The short answer is: none whatsoever,” says Thomas Rea, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and the director of the Center for Progress in Resuscitation. “Tobacco was a known stimulant, so the logic was it might help stimulate response and resuscitation.”

Eisenberg provides an additional hypothesis for its use, writing, “It is possible that the dilation of the anus by the tube provided some reflex stimulus of respiration.”

And before its toxic effects were understood, tobacco smoke was thought to have therapeutic qualities. In 1660s England, tobacco fumigation (in this case of the lungs) was believed to be a prophylactic against the plague. As late as the mid-19th century in America, it was considered a disinfectant, particularly against cholera. But Rea says he’s never come across the use of tobacco smoke for “therapeutic intervention” in modern medicine. “There is no modern evidence to support its use in this situation,” he says.

Criticism of the practice did eventually arrive. “When nicotine was discovered to be a poison, the critics became more harsh in the beginning of the 19th [century], but without leading to a learned consensus about the legitimacy [and] efficiency of the method,” says Anton Serdeczny, a senior research fellow at the Medici Archive Project in Florence, Italy, and author of Du Tabac pour le Mort: Une Histoire de la Réanimation (Tobacco for the Dead: A History of Resuscitation).

Rectal fumigation is, obviously, not CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation). “There was no idea about the respiratory chemical process at least until the end of the 18th century,” Serdeczny says.

Anecdotal reports of rescuers using chest compressions appear at the same time tobacco enemas were being used, but physicians of the day did not understand which methods of resuscitation were truly working, and certainly not how. For example, though 18th-century medical professionals did grasp the importance of circulation to vitality, says Serdeczny, “most practices around resuscitating the drowned were meant to restore respiration, in order to, as a result, restore circulation — as if the respiratory arrest was merely an obstacle to the continuation of circulation.”

It would be more than a century before medicine understood that resuscitation requires the combination of both respiration and circulation, and in the case of ventricular fibrillation, electric shock. The first successful defibrillation using electricity was recorded in 1947; what we know as CPR was not developed until the mid-20th century.

Some of the original lifesaving societies exist in different forms today: Early rescue societies in the U.S. later evolved into the present-day United States Coast Guard, and the Royal Humane Society continues to recognize acts of bravery by ordinary citizens. Perhaps most profound is that the work of these organizations, in their earliest forms, advanced our ability to reverse sudden death and paved the way for one of our most effective life-saving tools: CPR.

A Mouth-to-Mouth History

Ironically, blowing smoke into the rectum may have been preferred to blowing smoke into a drowning victim’s mouth: “In 18th-century England, the practice of placing one’s mouth on the mouth of a lifeless adult was considered particularly repugnant,” writes Mickey Eisenberg in Life in the Balance: Emergency Medicine and the Quest to Reverse Sudden Death.

Midwives had likely been practicing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on their neonatal patients for centuries, but were often isolated from and looked down upon by the medical profession; historical analyses refer to their technique as “inelegant,” “undignified” and “the method practised [sic] by the vulgar to restore stillborn children.” By the late 1700s, though, doctors in Europe began to recognize the value in the practice of forcing air into sudden-death victims’ lungs, advocating it to and through life-saving organizations. But instead of being seen as the first and most necessary step for resuscitation, rescue breathing was often considered one option of many — including blood-letting and rectal fumigation — and of lower priority than warming and drying the body.

By the end of the 18th century, distaste for actual mouth-to-mouth contact — “it was degrading to touch those who had died an Unnatural Death,” a 1796 account states — had caused mouth-to-mouth rescue breathing to be largely replaced by ventilation via bellows, metal tubes, and wooden pipes. Today, guards, shields and masks (such as the one shown above) are recommended for those performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation — not because such contact is “vulgar,” but rather to inhibit the spread of communicable diseases.