ScienceDaily has a report on a presentation Mark Shriver gave at AAAS meething this year:

"We started with 22 landmarks on the faces that could be accurately located in all the images," said Shriver. These landmarks might be the tip of the nose, the tip of the chin, the outer corner of the eye or other repeatable locations. They then recorded the distances between all the points in all directions, so they had a distance map of each of the faces. From their DNA profiles, Shriver could determine the admixture percentages of each individual, how much of their genetic make up came from each group. He could then compare the genetically determined admixture to the facial feature differences and determine the relative differences from the parental populations. "This type of study, done on admixed populations shows that each person is a composite of their ancestors and that the range of facial features is a continuum," says Shriver. Shriver found that there was a very strong statistical correlation between the amounts of admixture and the facial traits.

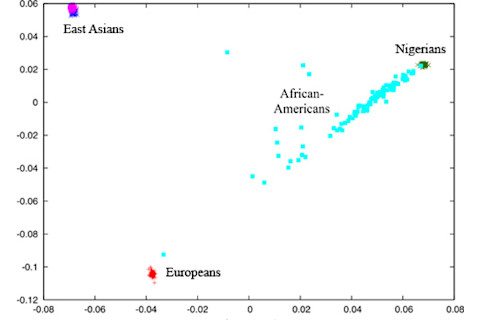

Black Americans are on the order of 20-25% European in ancestry and 75-80% West African. But these proportions are average over the whole population. Individuals vary in blood quanta:

Common sense would tell us that the more ancestry one has from a population, the more likely it is that one should exhibit the traits associated with that population. But there is some variance, and as I have noted before individuals with the same blood quanta may look very different, and favor different ancestral populations. But the variance around expectation is contingent upon the genetic architecture of a trait. The greater the number of genes which effect variation on a trait, the closer the inheritance pattern is going to resemble "blending." Since skin color variation is controlled a handful of large effect alleles segregating within the population it stands to reason that random chance is a powerful parameter when it comes to parent-child correlation of traits. More complex morphological characters might be controlled by so many genes that the likelihood that an individual will come to have an assemblage of alleles out of sync with its total genome profile could be sharply reduced (unless of course selection reshapes the frequencies of the alleles with the population).