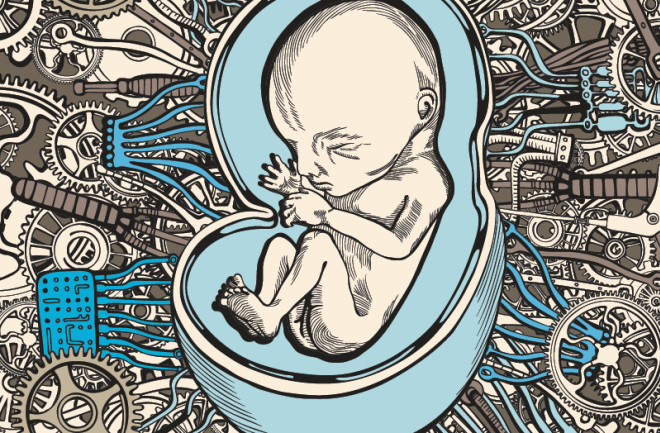

Picture rows of translucent tanks in a dark room. Partially formed embryos float silently, bathed in amniotic fluid. That’s the science fiction portrayal of an artificial womb, where machines gestate our babies, stirring unsettling undertones of inhumanity. It’s birth without pregnancy. As The Matrix’s Neo might say: Whoa.

While that’s still the stuff of fantasy, there have been serious attempts to create artificial wombs dating back to the 1960s. Most fell far short of the warm embrace of a real placenta. Scientists keep trying, partly because pregnancy is so complex, and, like anything else human, childbirth can go wrong, with consequences that affect a child’s entire life. Premature births occur in more than 10 percent of pregnancies and can result in heightened risks for lung diseases, cerebral palsy and developmental disorders.

For extremely premature babies, those born before 28 weeks of pregnancy, the statistics are grim: Thirty to 50 percent die, and up to half of those who survive experience some sort of health issue. The best we can do for preemies today is place them in a heated, humid incubator and pump in nutrients through IVs and tubes. Though we may not feel comfortable abdicating procreation just yet, humanity could clearly use some help.

The earliest attempts at fake wombs failed to sustain animal fetuses for longer than a few days. With improved technology, that marker was pushed back, but animals weaned on such systems still emerged with major birth defects — if they survived at all.

The latest step forward comes from researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), who successfully gestated premature lambs in an artificial placenta for a month. The lambs — removed from their mothers at the human equivalent of 22 weeks — developed normally inside the fake womb. They were born nearly indistinguishable from lambs birthed normally.

The device, called a Biobag, is basically a clear plastic bag filled with an electrolyte fluid. The fetus’s own heart pumps blood through an external oxygenator to avoid dangerous pressure differences. The lamb’s umbilical cord pulls in nutrients, and external heaters maintain a healthy temperature. The researchers even plan to pipe in recordings of the mother’s heartbeat as a soothing soundtrack. Their results were published in April in Nature Communications.

The Biobag addresses a crucial concern for fetuses: lung development. Once a baby’s budding lungs are exposed to air, there’s no going back, no matter what stage of maturation they may be in. The fluid environment of the fake womb, however, lets lung development continue unhindered.

Although the Biobag does mark a significant step forward for artificial womb technology, it’s not ready for human fetuses yet. For one thing, human babies are smaller, and downsizing the device could bring unforeseen complications. The scientists also have to find the right electrolyte fluid mix, and figure out how to connect to human umbilical cords.

These problems are surmountable, however, and the researchers say that they expect human trials in three to five years. Beyond saving preterm infants, the greatest benefit may be lowering life-altering birth defects by letting babies continue growing in a womb.

The looming prospect of gestation outside a woman’s body has some ethicists raising concerns, such as women being compelled to use the device to shorten pregnancy leaves. Dena Davis, a professor of bioethics at Lehigh University, sees this concern as overwrought.

“I don’t think anyone’s going to force a woman to have a C-section and use this thing,” she says.

Davis focuses instead on the potential benefits the technology could bring. “I actually think this could be a fabulous thing,” she says. “The absolute worst place for a preemie is a neonatal ICU.” The units can be bright, noisy and stressful.

Marcus Davey, a Biobag team member and developmental physiologist at CHOP, stresses that the device isn’t meant to reinvent pregnancy. He still doesn’t think it will work for babies born earlier than 23 weeks — a crucial window for development. And they don’t plan on trying.

“The main goal is to offer an alternate therapy for these infants born at 23 to 25 weeks,” he says. “The current standard of care is putting them on a ventilator and giving them a high level of oxygen. We’ve been doing that for 25 years, and mortality and morbidity rates in these infants, it really hasn’t shifted.”

[This article originally appeared in print as "Pregnancy, Interrupted."]